We’re approaching two years without functioning government in Northern Ireland, and this week the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland is driving legislation through Westminster designed to provide unaccountable and unelected civil servants with more power to make decisions over our daily lives.

“Well, at least someone is making decisions,” I hear you say.

Is that what it’s come to, really? More importantly, it doesn’t have to be this way.

Living in Scotland for the last few years, but maintaining a very active interest in Northern Irish politics, one cannot help but be unfathomably dumbfounded at the present situation.

However, in the spirit of offering constructive solutions, here is my tuppenceworth in the form of a possible package of institutional reform which would have the dual benefit of preventing this sort of impasse and incentivise actual power-sharing.

I wrote about the problem of the Stormont institutions and the incentives they create a while back for the Slant, but in light of Mike Nesbitt’s intervention on an arrangement to manage the impasse today, I thought it worth expanding on the idea of a more “normal” system of government which still maintains the important principle of power-sharing between nationalists and unionists.

Notwithstanding the political impasse between the parties on the well known issues of Irish language, legacy and equal marriage, it is the Stormont institutions that have failed us. This may seem a somewhat nerdy point, but institutional design matters. It really does, because it shapes the incentive structures and environment in which our politicians operate.

The Problem

The legislation that underpins the Good Friday Agreement, amended by the St Andrew’s Agreement, means all parties are entitled to be represented in the Executive if they secure sufficient support in an Assembly election. This is a well known model of government in deeply divided societies, but it comes at the expense of actual goodgovernment because of the number of parties in government and the lack of collective responsibility.

This means that no party can be left out of a coalition government in Northern Ireland if they meet a certain numerical threshold, no matter what. Therefore, there is no real need for any party to compromise or adopt a conciliatory tone prior to an election because they simply don’t have to – a bizarre state of affairs if one’s intention is to create meaningful power-sharing.

If that wasn’t difficult enough, after the St Andrews Agreement the largest parties in nationalism and unionism have been automatically awarded the roles of First Minister and deputy First Minister (no, that’s not a typo), rather than being elected by the Assembly as originally intended in the 1998 Agreement. This has impact of providing either of those parties with a veto over the other forming an Executive.

This allows any party, but particularly the bigger parties, which presently happen to be the DUP and Sinn Féin, to both issue and stand over “red lines” because they know that, legally, they cannot be left out.

It’s not difficult to see the set of perverse incentives this arrangement creates whereby parties are not rewarded for goodwill and compromise, but rather division and confrontation.

What’s more important is that it is only power-sharing by the letter of the law – it is certainly not power-sharing in the spirit that it was intended or as we badly need. It provides a forum for parties to share out power – and you only have to look at the findings of the ongoing RHI inquiry to see how a lack of collective responsibility can lead to catastrophic public policy mistakes.

I don’t doubt for a moment that our current arrangements were a political imperative of the time, but we are in a different place now and the status quo is quite clearly bonkers.

So, what of a potential solution?

The problem with moving to a completely voluntary model is that it could allow either nationalists or unionists to govern by majority – this is clearly a non-starter. However, there is a halfway house which would allow a more flexible coalition model but still maintain that important power-sharing imperative.

A Potential Solution

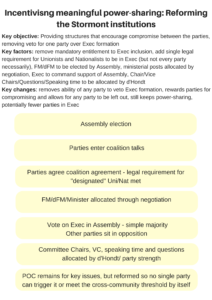

Firstly, we remove the mandatory entitlement to Executive inclusion, and restore the measure that requires the FM and dFm and the other ministers to be approved by a simple majority in the Executive. The only legal requirement for an Executive to be formed is that there are nationalists and unionists – as defined by the current designation system – in it.

Following an election, any/all parties and groups of independents enter coalition talks, and an Executive is formed from any combination that can command a majority in the Assembly on the basis of a traditional coalition agreement, provided the above cross-community provision is met. Any party that cannot offer enough compromise on its manifesto, or chooses not to be involved, is consigned to the opposition benches.

The First Minister, deputy First Minister and other ministers are also allocated by negotiation (removing the long established d’Hondt formula) and are subject to a vote in the Assembly.

To protect the mandate of larger parties who either cannot, or choose not to, be involved in government, committee chair/vice-chair positions, questions, and speaking time could continue to be allocated by proportionality or party strength.

A model like this would prevent parties issuing major red lines before elections, incentivise compromise after elections, prevent any one party from stopping an Executive being formed, and maintain meaningful power-sharing. It could also provide a positive good governance dividend through more collective responsibility and less parties in government.

This arrangement would not avoid the type of deadlock we’re experiencing indefinitely (only a purely voluntary model could achieve this), but it would make it much less likely.

Most importantly, however, it could create the type of power-sharing that was intended and that we badly need by incentivising government comprised of parties who want to work together for the betterment of everyone in Northern Ireland.

This is not a tearing up and starting again job. It’s a natural evolution of the structures in a new political context, and for which there is already precedent (opposition, reduction of departments etc).

There will no doubt be resistance to this suggestion, but to do so on the grounds of preciousness towards the institutions as they are is to be misguidedly focused on the process, rather than the outcome.

This type of power-sharing is not what we signed up for, and we all deserve better.