Election Day is less than five weeks away. Two polls have been released as the campaign for the seventh Northern Ireland Assembly gets underway; one from LucidTalk for the Belfast Telegraph and another from the University of Liverpool in partnership with the Irish News. They provide one of our last chances to examine the state of the parties before voters cast their ballots. They also give us an opportunity to consider how politics in Northern Ireland might be different after 5 May.

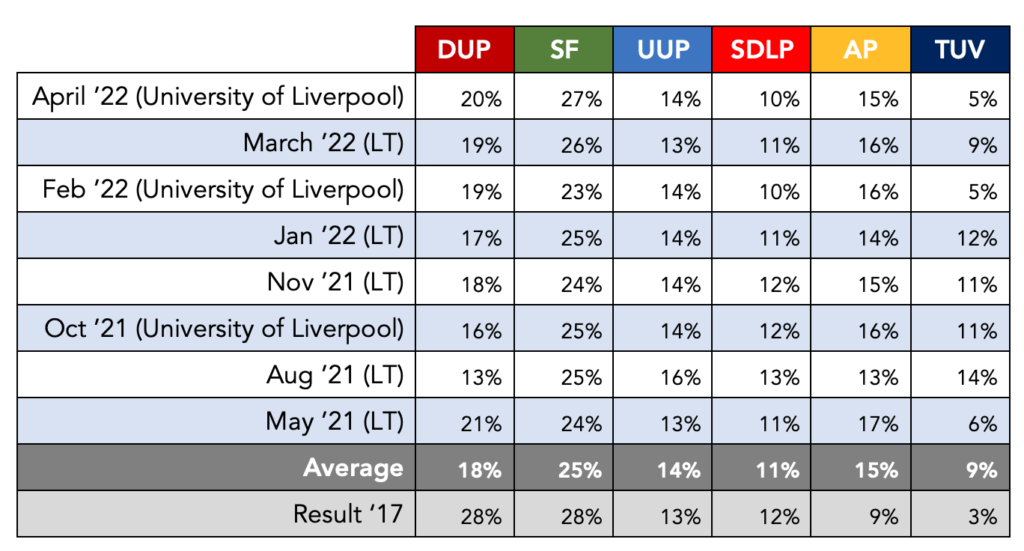

The table below summarises every poll on party support conducted in the last 12 months or so. We can see that there has been relatively little movement: support for the five main parties seems to be fairly settled.

Barring any major shocks over the next few weeks we appear to be heading towards a very close election in which both the DUP and Sinn Féin can hope to take the position of First Minister, with Alliance and the UUP fighting for third place.

The SDLP could finish anywhere from a close third to distant fifth depending on just a few thousand votes spread over several constituencies.

In terms of seats, the DUP may not emerge as far behind Sinn Féin once lower preferences are considered. Indeed, the TUV is unlikely to be in contention to win seats in many constituencies, but its voters can still make a difference. In 2017, TUV transfers went mostly to the DUP, followed by the UUP. A crude way of thinking about this is to just add a third of the TUV’s first preference vote share to that of the DUP; you can also give about a quarter to the UUP.

At this moment, Alliance looks well-placed to finish third. If its candidates avoid being eliminated early in each count they have the potential to overtake most other parties due to their transfer-friendliness. The party’s problem used to be avoiding those early eliminations, but that shouldn’t be as much of a problem this time around. In particular the Liverpool University poll included second preferences, and whilst much of this was expected, more UUP voters intend to give their second preferences to Alliance than to the DUP for the first time which could swing another seat or two.

Another factor in Alliance’s favour is the bizarre strategy of the UUP. The latter is running too many candidates in several constituencies, such as Fermanagh-South Tyrone and East Belfast, and an unpopular candidate in West Tyrone. Running candidates your own local party doesn’t want is a bad idea and could push Alliance over the top in that case. Running too many candidates can be just as damaging. The order of elimination can be crucial, so if the UUP ends up with two candidates each with fewer than a half a quota in one of those constituencies, they could well be overtaken by a party fielding a single candidate with a strong support base, such as the Greens or TUV in East Belfast.

The UUP should hold Fermanagh-South Tyrone, but if the party unseats its own MLA it will cause divisions further down the line, especially if it was its only female MLA.

Other parties

People Before Profit need to hold West Belfast, regaining a seat in Foyle is unlikely.

Neither Green seat is safe as South Belfast is highly competitive and its North Down seat was close last time under its then-party leader Steven Agnew, who has since stepped away from electoral politics. On balance it’s likely to hold both and it has an outside chance in East Belfast.

The independent unionist Claire Sugden should be fine in East Londonderry, given her established record. Pundits seem to be expressing some confidence that Alex Easton is safe in North Down. Easton is running as an independent having resigned from the DUP last year. Recently the activist Emma De Souza threw her hat into the ring in Fermanagh-South Tyrone. She has quite a high profile so could do well, although it’s a crowded field. She may hurt the SDLP’s chances of gaining a seat from Sinn Féin, although she could hurt Sinn Féin just as much.

The TUV should gain some seats. There have been plenty of estimates of where and how many, but it would be surprising if it got more than four or fewer than two.

Potential ramifications

If Sinn Féin comes out on top we will see largely performative outrage from the DUP. It’s unclear how Sinn Féin becoming the largest party, despite probably losing seats itself, is anyone’s fault other than the DUP’s – for (likely) losing even more seats.

The DUP has painted itself into a corner of red lines, making a period of direct rule a real possibility – if no government is formed even after four possible six-week negotiating periods. The DUP coming second would not be a great advertisement for the unpopularity of the Protocol, leaving even less chance of it ultimately being removed. It will ask for Article 16 to be invoked, but this would only suspend parts of the Protocol, not replace it – and any negotiations will be between the UK government and the EU. Moreover, even if the DUP does return as the largest party, which is still a possibility, we still may not have an Executive as it may continue to hold out until there are any major changes to the Protocol since that was the reason given for pulling their support for it in February.

What would happen under direct rule is uncertain, with the most likely outcome being: not much. It will mean that local politicians will have drastically reduced ability to respond to changes and will need to lobby the UK government for even the most basic new policies. It is unlikely that any of the parties will be able to fulfil any of their electoral pledges. We’ll see ongoing debates over how much, if any, of their salaries MLAs should get, a debate which will only increase public irritation with politicians of all stripes.

Direct rule may also exacerbate problems with the Protocol. We saw recently with the small reduction in fuel VAT that Rishi Sunak put forward that Northern Ireland would be exempt, at least temporarily. This kind of issue could crop up time and again. With a functional Executive, the money could be passed over as a lump sum in other ways so the parties here could come up with creative ways of spending it, as when some of our pandemic relief funds went into Spend Local cards. The Conservative government is unlikely to use its time and resources coming up with innovative policies: if it wants to trial a smart new policy it will do it in the North of England where it could at least win some votes. Instead, any extra Barnett Formula cash will likely be divided between the government departments where it will be spread thinly to prop up existing policies.

A radical overhaul of Northern Ireland’s healthcare system just won’t happen. It would be too difficult, time consuming and expensive for a government that holds zero seats in Northern Ireland to bother with. It has no skin in the game here. It also could mean the avoidance of any progressive legislation, such as the recent Integrated Education Act supported by Alliance, Sinn Féin, the SDLP and the Greens – and attempted to be vetoed by the DUP. This hints at another possible reason behind the DUP’s decision to walk away from power-sharing, at least in part. If the DUP can no longer block policies it doesn’t like, why should it sit at the head of an Executive responsible for those policies? If the DUP governing facilitates policies it dislikes and not governing blocks them, there is a logic to choosing not to govern.

It’s possible that some of the three smaller parties could opt to go into opposition, as they all did between 2016 and 2017. The UUP have hinted at going down this route, although they may not want to go out on a limb on this if Alliance and the SDLP decide to join the Executive. This would likely see Claire Sugden reprise her role as Justice Minister, although Alex Easton or the Greens may provide alternative options, assuming they are returned on 5 May.

There’s a chance that the five parties may try to agree a Programme for Government prior to the allocation of government ministries. This would be more in keeping with how coalition governments in other countries are formed and would likely lead to a more stable government as everyone would know their roles prior to the day the jobs are dished out via d’Hondt. It would avoid the spectacle that we saw previously in which the DUP, Sinn Féin and SDLP all publicly ducked the opportunity of taking the Health Ministry before the UUP bit the bullet.

Of course, whether any of that happens rests largely on whether the DUP either come first, or can swallow their pride.

This article has focused a great deal on the DUP because it will likely play a large role in determining whether or not we have a devolved government at all after the election. Under our rules either of the two main parties can stop us from having a functional government whenever they want and for as long as they want. Right now Sinn Féin is prepared to govern; the DUP is not. That Alliance, the SDLP and UUP would be willing to step in doesn’t matter because they can’t – unless, of course, the arithmetic changes more fundamentally than suggested by the polls.

If the devolved institutions at Stormont are to deliver for the people of Northern Ireland beyond the election, we may need to first rethink the rules that underpin them.