For Conor McGinn, peacebuilding is an ongoing journey we are all taking together. And the next logical step, he argues, is a Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland.

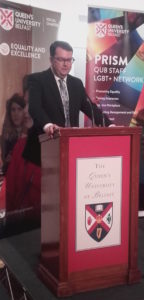

The Co Armagh native and Labour MP for St Helens North was at Queen’s University this week delivering the inaugural Equality and Diversity lecture – entitled “Rights, Responsibilities and Respect: Building the Common Good”.

Born roughly at the midway point between the first Civil Rights marches and the Good Friday Agreement – what he called two of the most powerful moments in recent Irish history – McGinn emphasized that both those events are as relevant as ever today “because the work isn’t finished.”

The “modest radicalism” of the Civil Rights movement in 1968 and the “ambitious pragmatism” of the Agreement thirty years later, he said, should act as a template and inspiration, a “compass to navigate the uncertain waters” we find ourselves in today.

“When I champion the Good Friday Agreement,” he said, “I do so as one of its beneficiaries.” And the fundamental mastery of the agreement, he said, was that it afforded rights to us all and “envisaged a respect that would emerge between peoples of different and still competing views.”

“Some people say the Good Friday Agreement has outlived its usefulness. That is completely wrong.” The architects of the agreement gave us the plans, he said, “but they left it to us, the people, to build the house together.”

Crucial to completing that construction, he said, was a Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland, such as was provided for in the Agreement, and for which the Human Rights Commission had drawn up a blueprint in 2008. In the absence of such legislation, he argued, progress was at risk, particularly in an environment where devolved government has been absent for as long as it has been.

The need for a Bill of Rights is becoming urgent, he said, emphasizing that in addition to enshrining rights for women and the LGBT community and enhancing “our common humanity” it would help the process of reconciliation by addressing the legacy of the past while focusing on the needs of survivors, families and communities affected.

“We are never going to agree about what happened in the past, but if you look at it solely through that prism, you’re condemned to live it all over again.” Victims deserve recognition, justice and peace, he said; but “I have yet to see any real willingness to approach [the subject] with an eye to the future, rather than an eye for an eye.”

On the subject of marriage equality, he said he had asked Northern Ireland Secretary Karen Bradley the previous day what message she wanted him to convey to people here, and she said to say she supported equal marriage.

“That’s great,” he said. “I support Tottenham Hotspur, but I don’t get to pick the team. She does have the ability to change the law.” And he called for action to see LGBT couples here treated the same as their counterparts in both Ireland and the UK. “We live in an age of ‘othering,’” he said, “of blaming those not like us for not being like us,” and cited John Hume’s words that “Difference is the essence of humanity; it should never be the source of hatred or conflict.”

Changing attitudes

During some wide-ranging questions, the subject came up of young people who had left Northern Ireland, not being content to “sit around and wait” for a better society. He talked about those who had moved away in part because of the “lack of a rights-based society” or a regression in social progress.

“The public supports steps towards social progress,” he said, pointing to how personal lived experience was changing attitudes. “There’s an inherent sense now that people should be treated equally, regardless of gender, race or sexual orientation,” and said he was at heart an optimist in his expectation for broader social change.

McGinn became the member for St Helens North in May 2015 and being an MP from Northern Ireland, but not “a Northern Ireland MP” has its own challenges, he said. “My motivation for speaking out about Northern Ireland is that I care about this place.”

A woman who described herself as a Labour party member asked about poverty and universal credit in communities across the country, and bemoaned the fact that Labour did not put up candidates in Northern Ireland. The detrimental effect of universal credit is “a rights issue,” he said. “I see in my own constituency a desperate need, and I told the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions that we’re not making this up. The obvious solution – and you’d expect me to say this – is that we need a change of government. Unfortunately they’re in power and we’re not.”

When McGinn’s party leader Jeremy Corbyn spoke at Queen’s a few months ago, the New Statesman reported that the reception he received “was so rapturous … it was easy to forget that nobody in the room could vote for him.”

On Brexit, McGinn said he didn’t enter politics “to make people poorer” and that the current deal being offered by the prime minister was a bad one. “It erodes workers’ and consumer rights and environmental protections.” But he said that while there were many reasons to vote against the deal, its provisions as they affect Northern Ireland are not among them. He was in favour of a people’s vote – and had moved to a point where such a vote might include an option to remain.

McGinn’s constituency voted to leave; and at a separate event on Friday in Belfast, he said he would be voting against the draft deal because it was bad for his constituents. “But I understand how frustrating it is for people here because Northern Ireland voted to stay in the EU.”

Also published on Medium.