Waking up to the news of the UK’s departure from the EU on 24thJune 2016, few people could have expected to be voting in elections to the European Parliament three years later. Or that a new ‘Brexit Party’ would be returned as the single largest party out of 751 MEPs from across the EU. Or that the Conservatives would be in fifth place. Or that Labour and the Conservatives would receive a mere 22% of the popular vote between them.

This was an election that defied the usual script.

The same was true in Northern Ireland – but here the results tell a different kind of story. And it’s a story that deserves attention. Turnout was 45% – relatively low by Northern Ireland’s standards, but some 8 points higher than the UK average. Plus, when you consider the (for some, unexpected) challenges of exiting the EU in a way that takes into account the complexities posed by Northern Ireland’s unique circumstances, it is worth paying careful attention to what its voters have said in this part of the UK.

And after the dramatic collapse of the power-sharing institutions at Stormont in January 2017, followed by a bitter election campaign, it looked like Northern Ireland was entering a new phase of inevitable polarisation along ‘orange and green’ lines. The ‘middle-ground’ was apparently disappearing; the spirit of compromise squeezed out by more rigid ideological forces, reinforced by new uncertainties over Brexit.

Yet, after a strong performance in local elections earlier this month, the Alliance Party was well placed to compete with the UUP and SDLP in the tight race for Northern Ireland’s third seat in the European Parliament (held by the UUP, which has represented Northern Ireland in Brussels and Strasbourg since 1979). As it turned out, Alliance’s Naomi Long succeeded – not in scraping through to take the third seat, but in sailing through to take the second.

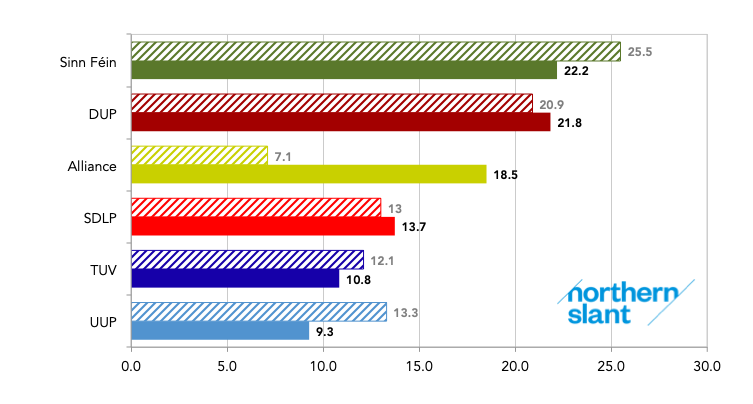

A recent pre-election poll from LucidTalk had reported solid levels of support for Sinn Féin’s Martina Anderson and the DUP’s Diane Dodds, suggesting that they would each be elected comfortably (as they were), with little change on their 2014 performance. Meanwhile, the poll found that Naomi Long was in a statistical dead heat with the UUP’s Danny Kennedy and the SDLP’s Colum Eastwood. Much would depend on a large pool of undecided voters and the extent to which the supporters of each candidate were committed to turn out and vote.

When the results of the first count were announced, things weren’t quite so close after all. While Colum Eastwood held up the SDLP’s 2014 vote, the UUP’s vote share fell by 4 points. Having more than doubled (or nearly trebled) Alliance’s previous share of first preferences, Naomi Long emerged comfortably ahead of both main rivals on the first count – to the extent that she came within a few percentage points of the DUP and Sinn Féin. That was, in itself, a remarkable performance for a party that has found itself in fifth place – or lower – for much of its 49-year history.

For context, you have to go back to 1994 to find the last time the UUP polled at least 18.5% of first preferences in a European Parliament election, and 1999 for the SDLP. It’s also worth recalling that the DUP secured 18.2% of first preferences in 2009. In other words, this was not a normal day in the office for the Alliance Party.

It looks like Alliance was able to attract a significant number of first preferences from voters who had previously supported a unionist party – namely, the UUP. But Naomi Long was also able to attract transfers from across the political spectrum. The rates of these transfers varied, of course, but they all add up – especially when other candidates are more constrained in their quest for transfers. For example, while only 2% of UUP transfers went to the SDLP, 13% went to Alliance. Similarly, while only 3% of DUP surplus votes were redistributed to the SDLP, 13% went to Alliance. And, crucially, when it came to the re-allocation of SDLP first preference votes, 34% went to Sinn Féin, but nearly twice as many (66%) went to Alliance.

Alliance has been firmly positioned as neither unionist nor nationalist on the political spectrum. In many elections, this has been a weakness for the party, with many voters instead (very legitimately) supporting parties with nationalist and unionist ideologies, and wanting to maximise the strength of their preferred bloc relative to the other. In this election, however, Alliance’s centrist position enabled it to build a cross-community coalition – reflected in both first and lower preferences of a broad range of voters. The main reason it has been able to do so has been the new context created by Brexit, combined with widespread dissatisfaction with the ongoing stalemate at Stormont.

A majority of unionists voted to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum, but a large minority opted to remain. Having been largely overlooked by each of the main unionist parties, Alliance offered a more appealing alternative for those who – in this election – think that Northern Ireland is being pulled in the wrong direction. This doesn’t mean that they are abandoning their support for Northern Ireland remaining in the UK, but it does illustrate that voters cannot be easily reduced to two homogeneous blocs.

Indeed, in this election, the main divide was not between unionist and nationalist, but between leave and remain, between anti-backstop and pro-backstop, with a general sense of frustration thrown into the mix. In total, parties campaigning to remain in the EU (but also supportive of the backstop in the Withdrawal Agreement) secured 57% of first preferences; parties campaigning to leave the EU (and staunchly opposed to the backstop) received 43% of the first preference vote share.

Perhaps the DUP’s pre-election message was bang on. They called on voters in Northern Ireland to “Tell them again!” It seems that voters responded, broadly echoing the 56% Remain/44% Leave distribution of votes in the 2016 referendum in Northern Ireland. There never was a single view on Brexit shared by people across Northern Ireland, and that reality has been reinforced: the position of the DUP, while supported by many, should not be taken as an expression of the view held by a majority of voters.

Viewing these election results through a more traditional ‘Northern Ireland’ lens, it is noteworthy that neither unionist candidates nor nationalists received a majority of the vote share: unionist candidates received a combined 43% share of first preferences (down 8 points on 2014), nationalists received 36% of first preferences (down 3 points), while ‘other’ candidates received 21% (up 10 points). A new competitive space is opening up in Northern Ireland’s electoral landscape, fuelled by new debates around Brexit and declining tolerance for the politics of non-governing at Stormont. This new development may not last, but its immediate significance should not be underestimated.

These results do not fit easily within the broader narrative of this European Parliament – at least in most other parts of the UK. The dominant story of the election has been the ‘surge’ in support for parties at either end of the Leave/Remain spectrum: Brexit Party and the Liberal Democrats respectively (with Scotland sending a message of its own). On the whole, compromise doesn’t appear to have been a vote winner in this political climate. But the same cannot be said in Northern Ireland. It seems that common ground has been discovered in the unlikeliest of places.