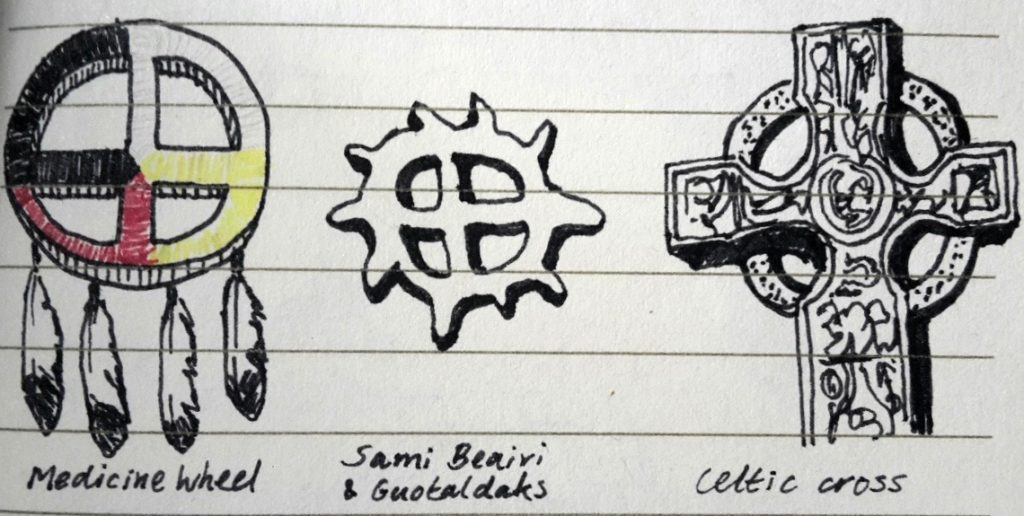

I am fascinated by symbols, and recently the Celtic cross has captivated me. We know the cross as a Christian symbol, and we know the story that accompanies it. But the cross as I have seen it here, resembling a symbol found in many indigenous traditions, evokes an entirely different reading.

As per the nature of this universe, we orientate ourselves in relation to time and space. We always want to know where we are and what time it is. Both time and space we divide in quadrants: the four seasons and the four cardinal directions. Winter spring summer fall, and north east south west.

These are connected: winter is the north of time, and north is the winter of space. They all derive their characteristics from the sun, which brings or takes light, and brings or takes warmth. The sun propels the movement through the aspects of the whole, integrating them in a perpetual cycle. Take the circle away, and you get unchecked expansion in all directions, you get Nietzsche’s “earth unchained from its sun.” They were a sensible people, history’s countless cultures who had a sun god to worship, from Ra to Apollo to the Gaelic Lugh. The Celtic Christians had the vision to have the circle bound their cross.

Circle-bound or not, there is a lure in the outstretched arms of the cross, beckoning us to follow their reach. Before we do though, a moment in honour of maps. The skill of map reading for a long time belonged to the realm of magic, a privilege reserved for the educated few – druids, scholars and kings in these lands – and out of reach of lay folk, whose perception was tethered to ground level.

Now we each have the power in our pockets, the knowledge in our minds, and the pixie dust of imagination, to orientate and align ourselves on a planetary scale. Let us travel together to the extremities of the four directions, the High North, the Far East, the Deep South, the Wild West, to find that however far we travel along the arms of the cross, the circle will lead us back to where we are, and to gain an appreciation for where that is.

N 55° 12′ 27″ W 6° 12′ 31″

It is 9:15pm when we lift off and travel East, out of the Croí towards the sun that’s rising beyond the horizon. On the other side of the promontory of Fairhead we enter the Irish Sea and soon Scotland looms ahead. We cross the south side of the Highlands, and enter the North Sea again from the shore of Northumberland. For a while, nothing but the sound of dark offshore waves in the night. It is 10:15 where we are now. Then we see the shore of Jutland, mainland Denmark, from where the Vikings left to first land on Rathlin Island 1,223 years ago.

Beyond the Danish islands we enter sea again, the shore of Skåne in Sweden in sight on our left. Briefly we pass over the island of Bornholm, and come on land again on the border between Poland and Lithuania. Soon we are in Russia, and the city lights of Moscow light up the night sky to our left. Then we plunge into the night again, and below us in the dark the rivers Wolga and Kama meet. There is tundra below us, and the border with Kazakhstan.

Now we fly over endless coniferous forests, as far as the eye can see. We are above the taiga, the largest biome after the oceans; a third of all the world’s trees live here. These are the lungs of Gaia; below us our living planet is exhaling the oxygen that inspires us. The Russian and Eastern Siberian taigas, which we are passing over now, cover nine time zones all on their far-flung own. It is 7am in the place where we first see sea again, and the sun. It is dawn now where we are, on the Sea of Okhotsk. One more time we pass over Russian land, the Kamchatka Peninsula, a remote place on the opposite side of this latitude.

Then we find ourselves skimming the northern rim of the Pacific Ocean. We are traversing the Bering Strait, where a troop of our primeval ancestors crossed over to the Americas some 15,000 years ago, more than 5,000 years before the first humans would set foot on the island of Ireland. A crescent of arctic islands juts out as the remaining piers of that ruined land bridge. It is 1pm local time when we enter land in Canada, Vancouver Island to our far right. We are back above a familiar sight: cities and pastures, but also more taiga now that stretches across British Colombia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, with a glowing city on the other side of Lake Winnipeg. Ontario, Quebec.

On the shore of the Labrador Inuit lands, at dusk now, 6pm local time, we enter sea again. We follow the planet’s curve across the North Atlantic, and leave the sun beyond the horizon, behind us this time. Nothing but the sound of dark offshore waves in the night. Finally we see the coast that keeps our breathing bodies, the shore of Donegal from which the Earls fled their beloved Ireland five centuries ago. We pass over the city nightlights of Derry, along the North Antrim Causeway coast and past Ballycastle we enter the Croí from the West, and return here to where our bodies wait.

But we can’t stay for long. Our minds circle the Croí once, twice, and off we shoot again, traveling south, out of the Croí past Knocklayd mountain on our right. We fly on over the undulating hills of Irish countryside. We pass the eastern shore of Lough Neagh, which the Gaelic giant Fionn mac Cumhaill created in times gone by when he tore a piece of land from Erin and hurled it into the Irish Sea, where it became the Isle of Man. On we fly, past the nightlights of the Viking town of Dublin, and leave Ireland at the port of Rosslare.

We pass over the Isles of Scilly off the Cornwall coast. All of France we leave to our left, and first enter land again on the dry coast of Spain. Smell the air, feel the cool night breeze, how is it different to your senses than the Irish wind? South of Spain, and to our left, we sea the landmasses of Europe and Africa stretch out to touch, the heavily patrolled Strait of Gibraltar between them.

We are above Morocco now, and the colour scheme of the Ireland’s greys and greens has been replaced by different shades of sand, on the verge of the Great Sahara Desert. Sand is all there is now, faintly glinting in the moonlight. We can just make out the contours of dunes and valleys, plains and mountains, rising and falling and rising again. We follow the border between Mauritania and Mali, and where we begin to see the stubble of shrubbery, and the air gains some drops of vapour, the border veers off to the right and we are above the Malinese prairie, and then the forests of Côte d’Ivoire. Too soon we’re leaving the lush and plundered lands of Africa and are above the Atlantic Ocean again, zooming across the equator.

The only relief we get from the endless ocean views is the remote island of St Helena, abandoned in the middle of the Atlantic. We move on, more waves, the never-ending rumble of Gaia’s tides. At last, land in sight. But it is white, and cold air bites our faces. The desolation of Antarctica: some wandering albatrosses, and a population of penguins huddling together in the furious frigid storms. Through blizzards we pass, blinded, and emerge on the other side of the South Pole, back over sea: we have reached the Pacific.

South-east of New Zealand we are above our antipode, the exact opposite of the planet. We see Fiji and Tuvalu down below. We are now traversing the blue side of the planet. As far as we have traveled south, the same distance we must now travel north, and it will all be water. But there is more on this invisible face of our planet, the dark side so cleverly obscured from our imagination by our deceptive world maps. Here we also find the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a floating continent cycling round and round, trapped in the North Pacific Gyre. We leave it behind us, and reach the eastern shores of Kamchatka again, and the crescent islands of the Bering Strait we’ve seen before.

Farther north we fly, across the far corner of Chukotka, and into the Arctic Ocean. Ice floats, large and suspended, a magical, strangely quiet landscape of whites and azure blues. We come to the North Pole, feel the static charge in the freezing air, and momentarily decelerate as we pass over the crown of our planet… before plunging southwards again, down the zigzag of the Mohns Ridge fontanelle fault line, dividing the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. We pass between Greenland on our right and Spitsbergen on our left, and see rock among the ice. We see the speck of land of Jan Mayen and the Faroe Islands.

Now Scotland looms below us, the Hebrides off the fjordland coast. Lewis and Harris, Skye, the Paps of Jura and Islay, seat of the Clan Donald, whose MacDonnell branch also laid claim on North Antrim for three centuries, building a string of coastal fortifications, one of which we now see on its glinting white chalk headland under the moonlight beyond Rathlin: Kinbane castle guarding the west flank of Ballycastle, just as Fairhead guards its east.

Dark Fairhead contrasts against the lighter night sky, still the iconic beacon of homecoming it was to the WWII Allied convoy ships this remote sea corner was once teeming with, sign of having reached the safety of the U-Boat free Irish Sea. Here we too find homecoming, having journeyed a full 24 hours horizontally and 24.900 miles vertically, and yet, only ten minutes after we set off, we now blow into the Croí with the cold North wind still on our neck.

Welcome back.