This week, in the fourth part of our summer series, ‘Movies and Shakers’, we take a look at some significant movies with a political theme that have had storylines set in Britain or featured British political leaders. Obviously we had something of a Churchill renaissance recently with Darkest Hour and Dunkirk igniting debate – of course – over whether Britain’s greatest wartime leader would have been a supporter of Brexit (spoiler: probably not).

Regardless, Gary Oldman gives a pretty remarkable performance as Churchill in Darkest Hour and serves to show, albeit in extreme circumstances, a relationship between the people and their political masters that has long been the stuff of nostalgia.

During the second world war itself, Carol Reed’s The Young Mr Pitt (1942) starred Robert Donat as Britain’s youngest prime minister and the story of how his career is intertwined with that of Napoleon had definite deliberate echoes of the ongoing struggle against Hitler. Later representations of Pitt were, shall we say, less heroic.

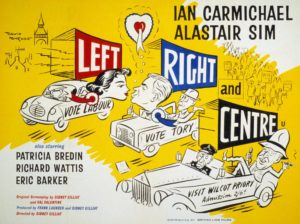

In the post-war period, with a Labour government in power, the Boulting Brothers’ Fame Is The Spur (1947), an adaptation of Howard Spring’s novel, traced the career of an idealistic politician who, surprise surprise, becomes the victim of expediency and compromise; while a comedy like Left, Right and Centre (1959) helped portray party politics as good old fun and games stuff in reconstruction Britain, where it was possible for opposing candidate to have a more than civil relationship while running against each other.

But there were grittier topics too, with politics as an inevitable backdrop, with realist “kitchen-sink” movies of the time addressing shifts in the social structure, like Look Back in Anger, The Loneliness of The Long Distance Runner, or Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

In 1961’s No Love For Johnnie Peter Finch plays an ambitious Labour politician whose personal life threatens to overwhelm his career – a theme obviously revisited in 1989’s Scandal about the events of 1963’s Profumo scandal and how it “kicked off the sixties” and ushered in an era of cynicism about politics and politicians. (Not to be confused, of course, with the BBC’s excellent recent mini-series A Very English Scandal, about a whole other political affair.)

In 1970, the comic genius of Peter Cook showed the potential for the still-nascent world of polling and political manipulation in the satire The Rise and Rise of Michael Rimmer, with John Cleese and Graham Chapman co-writing and David Frost as executive producer. The movie also had some interesting things to say about personality, power and, presciently, referenda.

And, because nothing is really ever “new” in popular culture, a previous round of “Churchillmania” had been unleashed in 1972 when Simon Ward played the lead in Young Winston, the “rousing adventure” of the politician’s early life, and how his character was formed long before he vowed to “fight them on the beaches.” The compelling nature of charismatic politicians will always be good box-office.

So much for history

There seemed to be a time not so long ago when you couldn’t go to the movies without seeing the brilliant Michael Sheen as Tony Blair. He played the prime minister-in waiting in The Deal (2003) chronicling his partnership with Gordon Brown (and even Rory Bremner had a take on their subsequent falling-out); as well as in The Special Relationship alongside Dennis Quaid as Bill Clinton. (Although, frankly, if you’ve seen Quaid as the President in the very funny American Dreamz, that’s a hard image to shake.)

But the role that brought Sheen to prominence was alongside Helen Mirren in The Queen (2006), the story of how Blair read the mood of the country, and the vulnerability of the royal family, to seize the political initiative following the death of Princess Diana.

But perhaps Sheen’s best performance of that whole period, even including the wonderful Frost/Nixon, was in dealing with a whole different type of politics – the very definition of a political football, in fact, but again focused on the nature of leadership – in The Damned United, another collaboration between Sheen and screenwriter Peter Morgan.

Just as Helen Mirren’s portrayal of Her Majesty was so pitch-perfect that you likely forgot after a while it was actually an actress up there, the same could probably be said for Meryl Streep’s performance as Margaret Thatcher in 2011’s The Iron Lady. Despite disputes over the historical accuracy of elements of the movie, it offers an insight into the mindset of Britain’s most divisive political figure for a generation.

In a previous installment of our series we looked at some great British political mini-series from around the Thatcher-era, like A Very British Coup, and how the issue of American nuclear weapons became such a hot topic for drama with Thatcher and Reagan in office. That theme was explored in Defence of the Realm, a 1986 movie with Gabriel Byrne as a crusading journalist who falls foul of military secrecy.

The dysfunction in the special relationship has also been explored more recently by Armando Iannucci’s movie In the Loop, a big-screen extension of his political satire series The Thick of It.

While the Falklands War provided the context for 1980s TV dramas like Tumbledown (for the BBC) or The Ploughman’s Lunch (for C4), the social aspects surrounding Thatcherism were ripe for drama; particularly the miners’ strike and the government’s approach to the trade unions. But stories of economic hardship and workers’ resistance are, of course, timeless.

Letter To Brezhnev (1985) is a bittersweet look at working-class life in Liverpool; while Danny Boyle’s iconic Trainspotting (1996) explored drugs, poverty and economic anxiety in Edinburgh. Brassed Off (1996) tells the story of a colliery brass band and its members struggling with the closure of their pit; while The Full Monty (1997) looks at six unemployed Sheffield steelworkers and their plans to make money. Finally, Made in Dagenham (2010) tells the true story of a strike by female sewing machine operators at the Ford plant in 1968 and their fight for equal pay (and contrast it to how unions are portrayed in older comedies like I’m All Right Jack).

The future’s not bright

As for today and tomorrow, there has hardly been a more impactful representation of life in modern austerity Britain than Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake, even if there were some disputes over the accuracy of the day-to-day portrayals of life on benefits.

As if a dystopian Britain spiraling towards chaos in the present day wasn’t enough, there’s worse to come in the future, according to movies like 28 Days Later or, particularly, Children of Men (2006) based on PD James’ novel, which paints a bleak picture of the future of the human race. Is there hope? Watch this brilliant movie, one of the most acclaimed films of the 21st century. In my opinion, it’s little short of a masterpiece.

Finally, if you like your political commentary with a healthy helping of humor, poignancy and awesome knifework, look no further than V for Vendetta (2005) – the directorial debut of James McTeigue and the creation of the remarkable Wachowskis, who brought us The Matrix.

Based on Alan Moore’s 1980s graphic novel – although Moore famously distanced himself from the final movie – it tells the tale of what unfolds when Britain is run by a fascist political party led by an insecure authoritarian “High Chancellor” brilliantly played by John Hurt, who uses the mechanisms of the state to enforce obedience and control while those in power enrich themselves. But the people are finally waking up and as you can imagine are a bit pissed.

Along with the mask imagery, obviously, the quotes from this movie are just made for passing into the lore of popular resistance culture.

“People shouldn’t be afraid of their governments – governments should be afraid of their people;” or “Beneath this mask there is more than flesh. Beneath this mask there is an idea, and ideas are bulletproof.” But I think my favorite line is “A revolution without dancing is a revolution not worth having.”

There’s no arguing with that.

That’s our list. What have we left out? Let us know.

Following up on our most recent article, on movies about journalism, a couple of you suggested Sweet Smell of Success (1957) – and what it tells us about the power of an individual newspaper columnist played by Burt Lancaster. Happy to put that right and include it now.

Also, you may be interested in this piece by Ricki Morell at NiemanLab looking at the similarities between narrative journalism and writing screenplays. She looks at some movie scripts that have been adapted from true stories that started life as pieces of journalism. The process and the mindset required are fascinating.

Thanks for reading – and watching. In two weeks we’ll look at some political movies about Ireland, north and south. Then we’ll finish up the series with some of the best political protest songs and videos.

Also published on Medium.