The election was a success for Sinn Féin and a disaster for the DUP

When Martin McGuinness triggered this election, it was unclear whether the result would really be any different for Sinn Féin. In fact, with a new and untested leader, it could have proven a costly risk to the party.

It is now clear that neither Michelle O’Neill – nor Gerry Adams – really needed to do very much at all. The DUP decided to pivot attention away from its handling of the RHI issue and instead adopt one of the most tribal campaigns that we have seen in recent memory.

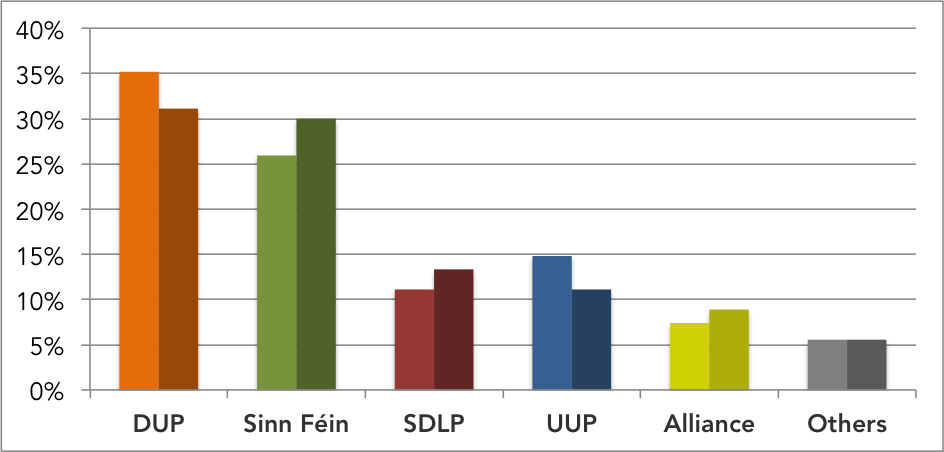

The percentage of seats received by each party in 2016 (light colour) compared to 2017 (darker colour)

It was intended to mobilise unionists to prevent Sinn Féin from emerging as the largest party. On the contrary, its main effect was to mobilise tens of thousands of nationalist voters to stop her from being returned as First Minister.

Despite the number of Assembly seats shrinking from 108 to 90, Sinn Féin have managed to return to Stormont with only one less seat – an effective gain of three seats.

The DUP’s total loss of 10 seats (an effective loss of four) has helped to put unionist MLAs in the minority for the first time in the history of devolved government in Northern Ireland.

This is a psychological blow more than a substantive one, but significant given the largely avoidable nature of this election.

People are not disengaged from politics

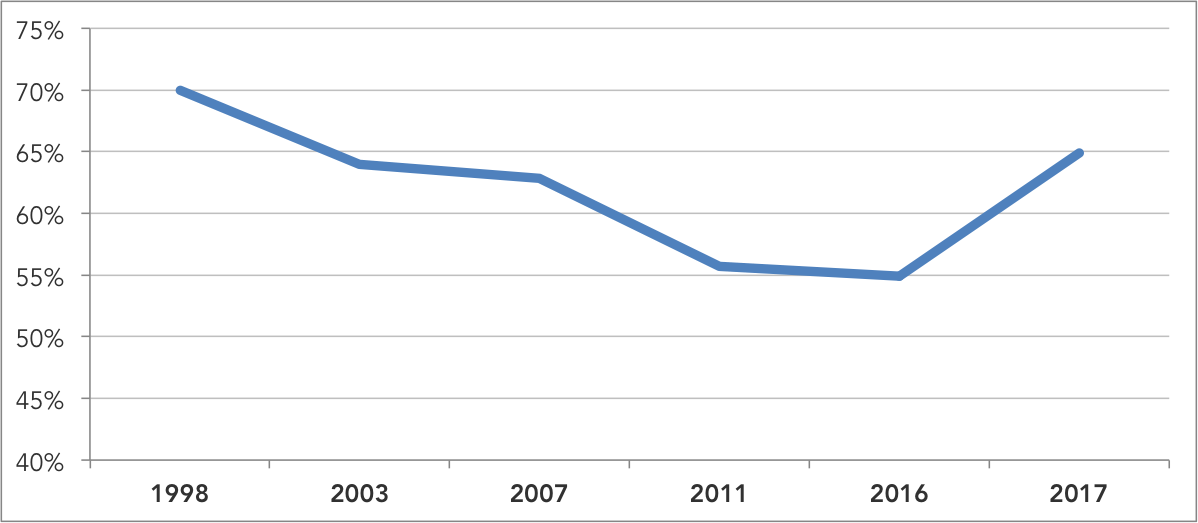

Voter turnout has never increased in a Northern Ireland Assembly election – until now. Nearly 65% of all registered voters took part, an increase of 10 percentage points on last May’s poll.

Voter turnout increased for the first time in an election to the Northern Ireland Assembly

The increase in participation was observed in all of Northern Ireland’s 18 constituencies; turnout increased by at least double digits in half of them.

The highest level was recorded in Arlene Foster’s home patch of Fermanagh and South Tyrone (at 73%, +8), and wasn’t far behind in Michelle O’Neill’s constituency of Mid Ulster, where the largest increase was recorded (72%, +13).

The increase in turnout challenges two assumptions: first, that people are increasingly disengaged from politics; and second that non-voters are necessarily more moderate than traditional voters.

A turnout rate of 65% would be considered healthy in most established democracies in 2017. What may be considered less encouraging is the likely explanation behind it: the combination of nationalist alienation and unionist fear.

The ‘centre ground’ is getting more cohesive

Whilst it far from obvious that previous non-voters flocked to the ‘moderate’ centre ground in droves, the combined performance of the SDLP, Ulster Unionists and Alliance constitutes modest success for these parties.

The headline figures aren’t particularly impressive, not least if the opposition parties wanted to seriously challenge the governing DUP and Sinn Féin rather than simply fight their corner. The vote share of the SDLP and Ulster Unionists changed by less than a percentage point in each case; Alliance recorded its best performance since the 1970s, but it remains in fifth place.

These modest changes on 2011, however, mask some fascinating developments below the ‘first preference’ picture. Mike Nesbitt has already fallen on his sword, with many criticising his apparently ill-judged intention to give the SDLP his second preference vote in East Belfast.

Some party colleagues immediately distanced themselves from his comments, urging voters in their constituencies to transfer to other unionist candidates first. The message appeared somewhat muddled and inconsistent, but it wasn’t alien to a large number of voters.

In Upper Bann, Ulster Unionist transfers helped to re-elect the SDLP’s Dolores Kelly at the expense of Sinn Féin’s Nuala Toman. In Fermanagh and South Tyrone, SDLP transfers helped elect the UUP’s Rosemary Barton over the DUP’s Lord Morrow.

In Lagan Valley, perhaps most fascinatingly, more Ulster Unionist transfers went to the SDLP’s Pat Catney than to the DUP’s Brenda Hale. Acknowledging the unionist transfers that got him elected, Catney remarked: “There is only one community. I want Northern Ireland to work.”

The opposition parties didn’t have long to show voters that they could offer an alternative, a more cohesive government. If, however, they plan to continue their cooperation after this election, their efforts are likely to be supported by a large number their voters.

Appetite for institutional reform may recede

When the former MLA John McCallister introduced a bill to legislate for an official opposition, he did so with other complementary reforms in mind. He wanted to reform the petition of concern (which gives a party an effective veto if it has 30 seats or more) in favour of qualified majority voting, and he wanted to rename the First and deputy First Ministers the Joint First Ministers.

These reforms, he argued, would be necessary to help remove an endless ‘us versus them’ dynamic in Northern Irish politics.

The DUP made significant use of the petition of concern in the previous mandate: with 38 seats, it lacked any incentive to reform it. Now, with no party possessing 30 seats or more, the mechanism may naturally revert to its intended use: as a means towards protecting a minority community, rather than any single party, against legislation that would discriminate against it.

As the resignation of Martin McGuinness demonstrated, the First and deputy First Ministers are effectively co-equal positions: one cannot do something without the consent of the other. It is, and has been, a joint office in all but name.

Only 0.2 percentage points separated the share of the vote received by the DUP and Sinn Féin respectively. The DUP returns with just one seat more than its republican rival. If anything, that makes it less likely that it will accept any renaming of the two positions to recognise their essentially equal status.

Of course, what the forthcoming post-election negotiations will yield is anyone’s guess.

Next stop, negotiations…

In this sense, Northern Ireland is far from unique. Most democracies use some sort of proportional electoral system that often requires some sort of coalition government to be formed. This process inevitably takes some time as parties negotiate a draft programme for government.

In Northern Ireland, political leaders now have three weeks to discuss the formation of a new Executive. This will be particularly difficult given two facts.

First, there is extremely little trust between the two largest parties. Indeed, it is arguably precisely because there was so little trust between the DUP and Sinn Féin before the election that the election occurred in the first place.

Second, both parties have stipulated ‘red lines’. Arlene Foster (infamously) stated her outright objection to an Irish language act during the campaign: “If you feed a crocodile it will keep coming back for more.”

On the other hand, Sinn Féin hasn’t made it easy for the DUP to go back into government as its partner. If there is any pressure on Arlene Foster to resign over her party’s poor showing in this election, it is almost certainly reduced by Sinn Féin’s insistence that she must not be nominated as First Minister if they are to share power with the DUP.

We’re used to tense negotiations in this part of the world, and we’re used to parties finding creative ways of reaching compromise when the stakes are high. If they don’t, then direct rule from Westminster will become inevitable. Our best hope for a return to power-sharing is that the two largest parties agree on at least this: that an indefinite return to direct rule would be a huge setback to the long-term future of Northern Ireland.