8 March 1973 was the last (and only) time that Northern Ireland held a referendum on Irish unification. The result delivered an overwhelming verdict: almost 99% of voters voted to remain part of the United Kingdom.

The caveat, however, was that most nationalists boycotted the referendum. Since the 1970s the political discourse has been that any future border poll would result in another heavy defeat for the cause of Irish unity.

Opinion poll after opinion poll has indicated that most citizens – across the political divide – would favour remaining part of the status quo.

Former DUP leader Peter Robinson even suggested that republicans getting a referendum on a united Ireland would be akin to ‘turkeys voting for Christmas’.

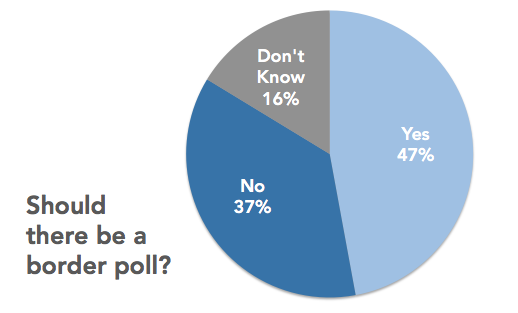

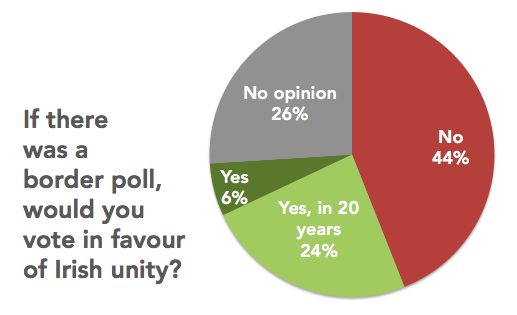

We are led to believe the DUP has in the past considered calling Sinn Féin’s ‘bluff’; a 2014 Belfast Telegraph poll also indicated that more people want a border poll to be held than not – to settle the issue once and for all.

Survey results from the Belfast Telegraph, 29 September 2014

The possibility of a border poll is a crucial part of the Good Friday Agreement, yet the conditions in which a referendum could be called are vague. The strongest argument for the criteria being met would be if a distinct change in public mood occurred – presumably represented by a changing shift towards nationalist political representation.

It appeared that as of May 2016, when the DUP was returned as the largest party, the border seemed as permanent as it had ever been…

Fast forward to March 2017. The recent Assembly election has created a precedent. Unionists are no longer form a majority at Stormont; and Sinn Féin is within reach of becoming the largest Northern Irish party for the first time.

In the DUP ‘bunker’, should a border poll be discussed, amongst many other questions, how might discussions proceed behind closed doors?

Politician A: ‘Hear me out. I wonder if agreeing to a border poll could pacify nationalism as part of an overall package to restore devolution and get the Executive up and running again?’

Politician B: ‘Surely all other issues, including demands for Arlene Foster to stand aside, would seem marginal if a referendum was accepted by the DUP?’

Politician A: ‘Well I suppose they could. And as Northern Ireland’s Centenary year approaches in 2021 a rejection of Irish unity would surely settle the question for decades? What a turn around this could be for unionism!’

Politician B: ‘I agree, and if we had a campaign which included members of other parties this could deliver a positive pro-Union campaign.’

Politician A: ‘I agree! When should the date for the referendum be? 2018?’

Contemporary politics has shown us that events can move quickly. With Brexit on the horizon, combined with a resurgent nationalism, acquiescence to a border poll could galvanize many forms of unionist opinion and settle the issue for now.

Why risk a tighter result in the future, should potentially detrimental consequences of Brexit materialise?

During the current negotiations, would Sinn Féin agree to a one time only Irish unity referendum as agreed by all parties? If republicans refused to accept such conditions, and maintained it had to be held every several years, how would they sell a clear rejection of their raison d’être to their core vote? This could be damaging.

In 1973 unionism experienced a period flux; this marked the beginning of decades of direct rule. 44 years later, whilst our society is no longer marred by violence, political deadlock characterises Stormont’s current operation; another stint of direct rule could be weeks away.

From this angle, agreeing to a referendum could be unionism’s ‘trump card’ to neutralise nationalism’s overriding objective before their resurgence takes hold.

If the DUP waits until a future date, Sinn Féin could by then be Northern Ireland’s largest party, with nationalists controlling an overall majority of seats.

They could also hold the balance of power within a coalition set-up in the Republic of Ireland. If that happens, a United Ireland could be a foregone conclusion. Could any amount of unionist ‘unity’ prevent it?