This is a story about survival – about what helped two women, in particular, toward a degree of healing following traumatic bereavements during the Troubles. It is the story of how women bore the brunt of suffering during the conflict, and about the complexity and length of the healing process. And it is the story of how that process has been helped by the Unheard Voices programme based in the Ráth Mór Centre in London/Derry.

The women – Sharon, from Protestant Waterside, and Ann (short for ‘Anonymous’) from Catholic Creggan – are from opposite sides of the Foyle. They met through Unheard Voices, belong to the core group of 20 members and can now say they “love each other to bits.”

The women – Sharon, from Protestant Waterside, and Ann (short for ‘Anonymous’) from Catholic Creggan – are from opposite sides of the Foyle. They met through Unheard Voices, belong to the core group of 20 members and can now say they “love each other to bits.”

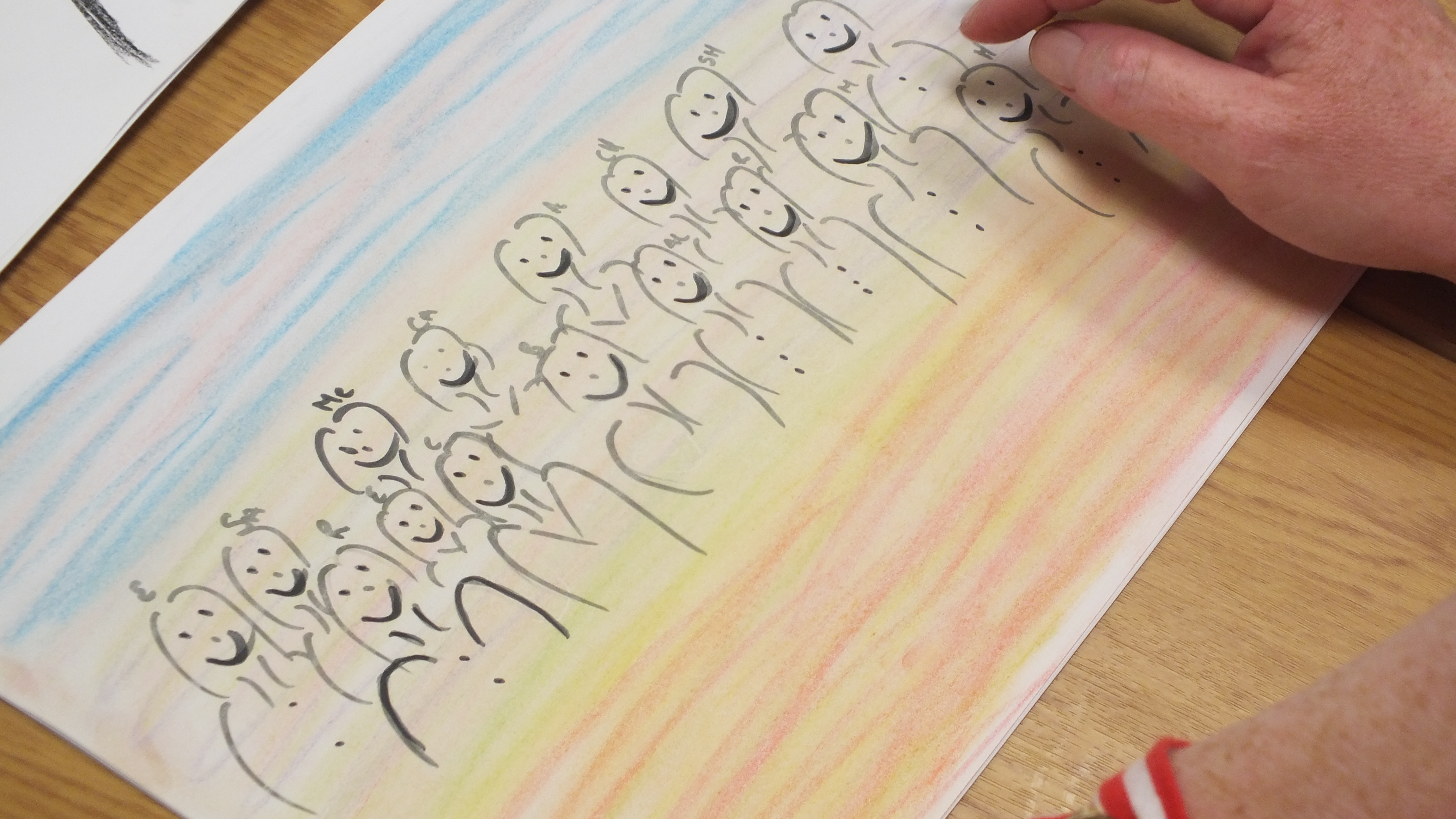

This is my third visit to Unheard Voices and my second time meeting these two extraordinary, strong and beautiful women. I am spending the day listening to their stories, along with Carol Cunningham, the project director, and artist Rita Duffy, who is here to draw and encourage the women to draw. The question is asked: What was particular to women’s experience during the Troubles, and why? What is the story that needs to be told? And the story that interests me most is: how do these women help themselves, and how are they helped to emerge as survivors from decades of isolation and trauma?

Sharon’s brother Winston was abducted, tortured and murdered by the IRA in 1974; Ann’s father was arrested and jailed in 1979 when she was four, and when he came out he disappeared with a new partner to Belfast. From the moment of loss, neither of the women’s mothers could cope. After Winston’s death, Sharon’s strict and controlling father became a violent alcoholic and her mother, obsessed with her dead son, became addicted to prescription drugs. The home became a “madhouse.” Sharon draws her mother, crying, with a shadow to represent her brother in the background, and a large poppy – he was killed just before Remembrance Day. Ann’s mother, who had a child each year from the age of 16, abandoned her four children after her husband was jailed and they were sent to their grandparents in Creggan. Both women went on to suffer multiple forms of abuse, violence and neglect.

Unheard Voices was founded almost five years ago by Carol Cunningham. From her experience on peace projects she knew there were many severely isolated and marginalised women victims of the Troubles who weren’t being reached by community projects. “If I ever get the chance,” she told herself, “I’ll deliver a programme from scratch that will really make a difference.” Having won funding from International Fund for Ireland’s Peace Impact Programme she began by going out into the community, knocking on doors, building relationships and gradually drawing women out of their homes. She wanted to work with women from both sides, including some who are still wedded to violence, as well as women who had lost relatives from the security forces. Unheard Voices brought these women together to learn that they had more in common than divided them. Many of them contributed, some anonymously, to the twenty-nine stories told in Beyond the Silence (Guildhall Press 2016), stories painstakingly gathered and recorded over eighteen months by Juliann Campbell.

Unheard Voices was founded almost five years ago by Carol Cunningham. From her experience on peace projects she knew there were many severely isolated and marginalised women victims of the Troubles who weren’t being reached by community projects. “If I ever get the chance,” she told herself, “I’ll deliver a programme from scratch that will really make a difference.” Having won funding from International Fund for Ireland’s Peace Impact Programme she began by going out into the community, knocking on doors, building relationships and gradually drawing women out of their homes. She wanted to work with women from both sides, including some who are still wedded to violence, as well as women who had lost relatives from the security forces. Unheard Voices brought these women together to learn that they had more in common than divided them. Many of them contributed, some anonymously, to the twenty-nine stories told in Beyond the Silence (Guildhall Press 2016), stories painstakingly gathered and recorded over eighteen months by Juliann Campbell.

The storytelling is crucial, says Cunningham. “The women want the world to know in the rawest form what the impact of the Troubles was on their lives.” Unheard Voices links some women with counselling and other services, such as CALMS (Community Action for Locally Managing Stress). They have engaged in a range of activities – but not the “soft stuff” like cooking and flower arranging – including a history programme with the Tower Museum, in which they looked at the ‘Speeches, Strikes and Struggles’ collection. Some women recorded the letters of Derry civil rights activist Bridget Bond. Some engaged in a genealogy programme to track down family members with whom they had lost contact. Women drop in and out as they please, but up to 200 women in all have been reached by the programme and 40-50 meet weekly.

The storytelling is crucial, says Cunningham. “The women want the world to know in the rawest form what the impact of the Troubles was on their lives.” Unheard Voices links some women with counselling and other services, such as CALMS (Community Action for Locally Managing Stress). They have engaged in a range of activities – but not the “soft stuff” like cooking and flower arranging – including a history programme with the Tower Museum, in which they looked at the ‘Speeches, Strikes and Struggles’ collection. Some women recorded the letters of Derry civil rights activist Bridget Bond. Some engaged in a genealogy programme to track down family members with whom they had lost contact. Women drop in and out as they please, but up to 200 women in all have been reached by the programme and 40-50 meet weekly.

Sharon draws a picture of her new housing executive bungalow, and proudly shows photographs of the immaculately decorated rooms. With a physical disability, for the first time she can reach the whole house. The move was, she says, at 55, the first decision she ever made for herself. What made it possible? Honestly, the death from cancer of her controlling, demanding, grief-stricken mother. As the only daughter of five children, Sharon had felt she was never good enough. But when her mother was ill, she “lay in bed beside her the last seven months of her life.”

Sharon draws a picture of her new housing executive bungalow, and proudly shows photographs of the immaculately decorated rooms. With a physical disability, for the first time she can reach the whole house. The move was, she says, at 55, the first decision she ever made for herself. What made it possible? Honestly, the death from cancer of her controlling, demanding, grief-stricken mother. As the only daughter of five children, Sharon had felt she was never good enough. But when her mother was ill, she “lay in bed beside her the last seven months of her life.”

“That was my childhood. I craved my mother’s love all my life, and when she was dying, I got it, she depended on me.” She is aware and articulate about her ambivalence toward her mother – a deep love combined with resentment at the poor treatment she received. On the inside of her wrist, her and her mother’s thumbprints are tattooed in the shape of a pink heart.

One gift she was able to give her mother was the story she told about Winston for “Beyond the Silence”. Her mother never read it, but died knowing Winston was being remembered. On the 40thanniversary of Winston’s death, Sharon organised, through Facebook, a graveside memorial, attended by 200 people, with a remembrance book and a piper booked by one of her brothers.

One gift she was able to give her mother was the story she told about Winston for “Beyond the Silence”. Her mother never read it, but died knowing Winston was being remembered. On the 40thanniversary of Winston’s death, Sharon organised, through Facebook, a graveside memorial, attended by 200 people, with a remembrance book and a piper booked by one of her brothers.

After her first marriage to an abusive man – “my father beat my brothers and me, and he beat my husband for beating me” – she “vowed I would become a strong person.” She met Robert, and has had a loving second marriage. But she remained isolated in her kitchen, rarely going out. “I could be in control of everything, and who came into the house.” Her husband would take her away for weekends in their motor home. “My children didn’t have a lot, but they loved going around Ireland in the caravan with me and Robert, because we were together all the time.”

Her confidence has improved immensely, she has a small group of trusted friends and she comes over to Ráth Mór to meet the other women. “People ask me, why are you, a Protestant, going over to Creggan? I still don’t trust people, but I feel safe here.”

Ann met her mother ten years ago at her granda’s funeral. She agreed to see her again, but said: “I don’t want to talk about the weather; I want to understand.” Her mother has regrets, says Ann who has persisted in building the relationship. “It’s not who I would want to be to say, go away I never want to see you again.” “Now I can say I love you, and she can say I love you back.”

Both these women seem to be driven by their capacity for love, which has somehow survived the years of abuse. Ann draws a picture of Diana, the American woman she stayed with in Chicago for just six weeks when she was eleven, who wrote her letters for years, and now comes over regularly to visit her and others she hosted on the cross-community programme. “There’s not enough words to describe the woman she is. She exudes love and I’ve never felt anything other than being her daughter. Someone seen you as a person and allowed you to be a child.”

And both women have been able to offer their own children the love they never received themselves. “When I had my daughter,” says Ann, “I thought, this is it. I never wanted my children to feel the hurt and pain I felt. They were going to have someone that loved them.” Now her three older children are all working and living away; her daughter is “well-travelled and confident;” and her younger son is “mad about his granny; now he can have the granny he never had.”

And both women have been able to offer their own children the love they never received themselves. “When I had my daughter,” says Ann, “I thought, this is it. I never wanted my children to feel the hurt and pain I felt. They were going to have someone that loved them.” Now her three older children are all working and living away; her daughter is “well-travelled and confident;” and her younger son is “mad about his granny; now he can have the granny he never had.”

Sharon says: “my daughter was the first thing in my life that was mine. I idolised her, and tell her three or four times a day I love her.” Her daughter says to her, “you are the glue in the family’s life.” As time has passed, Sharon and Ann have been able to have conversations with their children to explain why family structures had broken down, and why they were over-protective of them.

Despite all they’ve achieved for themselves and their families, the women agree: “The story doesn’t go away. For us, there isn’t a past, there’s some moment in every day that reminds you.” They tell their story over and again, and, says Ann, sometimes she comes away feeling exhausted, but “more often than not I come away feeling lifted, especially when someone says something you hadn’t thought about. It’s like therapy without being therapy.” “Re-traumatisation is part of the process,” says Carol Cunningham.

There is some evidence that there are increasing numbers of people – mostly, but not all, women –coming forward to report, or seeking help for violent and sexual abuse they experienced as children during the Troubles. This may have been due to a general breakdown of family structures and moral authority – perpetrators were almost always family members or other known individuals, and there was nowhere for women or children to go to report abuse or seek help or protection.

Speaking during the April Peace & Beyond conference, Professor John Brewer of the Senator George J. Mitchell Institute at Queen’s University spoke about the importance of social trust in peacebuilding processes – the ordinary daily trust between citizens, an inevitable casualty of conflict. From a six-year research study in Sri Lanka, South Africa and Northern Ireland, he has concluded that “first generation victims are moral beacons for forgiveness and magnanimity. He asks whether there is something in the traumatic experience itself which encourages this generosity of spirit. We need to learn from this, he suggests, because in Northern Ireland most of the effort since 1998 was invested in structures and governance – and not enough on building social trust.

It is quite clear that community development initiatives can contribute to improving social cohesion – and that the work takes years if not decades and requires painstaking effort at the individual as well as the group level. Unheard Voices, along with other programmes, faces funding crises just as they become truly effective. Funding has been affected by short-termism, austerity, the collapse of the Assembly, and the perception that the peace process ought to be complete by now. But the work needs to be sustained and embedded.

About the current state of politics in Northern Ireland, the women are scathing. They say: “The politicians are stirring up hatred and arguing about stupid things. For them it’s about power and money. Ordinary people are equal. We want them to give us peace and security.”