Northern Ireland’s political parties have had a few turbulent years to put it lightly. Since the referendum on the UK’s membership of the EU in 2016, they have been thrown into the middle of a volatile debate which has dominated politics across the Union, the island of Ireland, and indeed the entire continent.

The shifting nature of the debate on how Northern Ireland’s position in the post-Brexit UK could be reconciled with the desire to avoid an economic border on the island of Ireland proved to be the major sticking point in delivering Brexit. Internally, the Brexit debate has added another layer to the deep divisions in Northern Irish politics.

The Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol reached between the Johnson-led Conservative government and the EU in December 2019 came into effect at the start of this year. It sought to address the fundamental issue of how to manage post-Brexit trade and avoid a border on the island. While it went some way towards placating the worst fears of nationalists and the Remain-leaning centre-ground, the Protocol has been attacked by unionist leaders as an instrument which undermines Northern Ireland’s constitutional position within the Union.

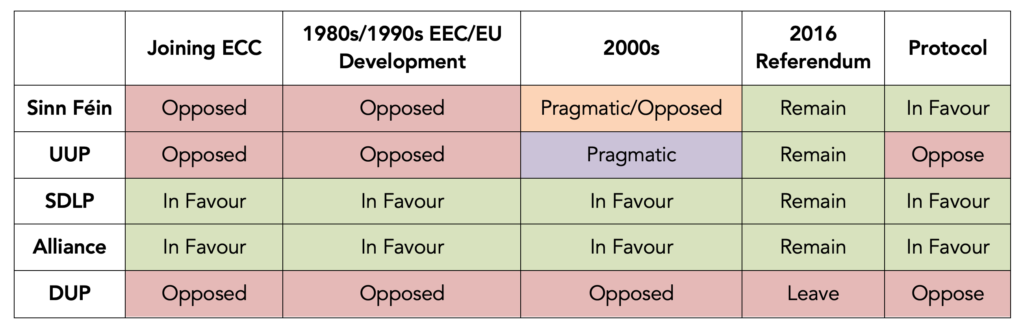

The EU’s momentary threat to trigger Article 16 of the Agreement at the end of January, has added fuel to unionist calls for the UK to scrap the arrangement entirely. To understand how each party now views the EU and the Protocol, we must understand their attitudes towards Europe over the years and decades, including the various shifts in position they have undertaken.

Party views on the EU and Brexit

The parties with perhaps the most straightforward and consistent view on Europe through the decades have been the SDLP and Alliance. The former has long championed EU membership as a common framework under which both sides of the island, and indeed both Ireland and Britain, could cooperate. Under their former leader John Hume, himself a long-time member of the European Parliament, the SDLP positioned themselves as a passionate pro-integration party at European elections.

Though Alliance had no representation in Brussels until Naomi Long’s success in 2019, the party also has a long track record in support of European integration and emerged from the 2016 referendum as the most visible remain force for pro-EU voters. This is something which greatly benefited them at the ballot box and contributed to their growth in the 2019 Westminster and European Parliament elections.

The DUP have had a relatively consistent, but a good deal more complicated, view on the European project. The party opposed membership of the EEC in 1975 and were somewhat unusual in Brussels in that they have never joined one of the party groups through which much of the business of the European Parliament is structured. They engaged quite constructively with the EU institutions when required to (including in the Executive and Assembly), but the DUP maintained their Eurosceptic stance when the opportunity arose and supported the ‘leave’ side in the 2016 referendum. In the referendum aftermath, the DUP became prominent opponents of the May government’s doomed EU withdrawal agreement.

Though they would not like to admit it, both the UUP and Sinn Féin have travelled quite similar journeys on Europe over the decades, before diverging from one another in recent years. Both parties opposed membership of the EEC in 1975 and maintained critical stances on the project in the following decades. However, by the 1990s/early 2000s, both parties began engaging with the EU in a more positive fashion.

The UUP did so through sitting alongside the European People’s Party group, one of the most prominent pro-integration blocks in Brussels. This allowed them to engage more closely with EU colleagues, and for their sole MEP, Jim Nicholson, to gain powerful internal positions in the Parliament. However, it’s also important to note that they did also have brief detours through membership of some of the Parliament’s more fringe right-wing and Eurosceptic groups over the years, including the Tory-led European Conservatives and Reformists. The shifting position on Europe over the decades left the party with little option but to allow a free vote on the issue for their divided membership, though the central party ultimately backed Remain.

Meanwhile, Sinn Féin joined the European United Left–Nordic Green Left group when their first MEPs were elected in 2004. While they continued to oppose new EU treaties in the periodic ratification referendums which took place south of the border, the party publicly adopted a self-described approach of ‘critical engagement’ with the European institutions. Come the 2016 referendum, Sinn Féin decided upon backing Remain, given the complications which could (and did) come down the line with regards to the border. However, it is worth noting that they did not get involved in the official Remain campaign or share a public platform with other parties.

Reaction to the Protocol

Since the details of the Protocol were announced in late 2019, each party has had to react to quite a technocratic instrument, but one which has profound economic and political implications. The DUP’s confidence and supply arrangement with the Conservative government was nominally ended by the increased majority Boris Johnson received at the ballot box in the 2019 general election, but was politically destroyed by the announcement of the Protocol arrangement prior to that vote.

The DUP vehemently rejected the Protocol in their own manifesto and described it as something which would “endanger the economic and constitutional position of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom.” Though Johnson was at this point describing it as an “oven ready deal,” the DUP appeared to hinge everything on being kingmakers once again in Westminster and said they still “want to see a sensible Brexit deal but no borders in the Irish Sea.”

The UUP blamed their fellow unionists for taking Northern Ireland to this point and said “Boris Johnson’s deal is not only a bad deal – it’s a disastrous deal. If it is allowed to pass it will put a border in the Irish Sea and would tear Northern Ireland away from its most important economic market – the market of Great Britain.”

Aside from unionist objections, the 2019 Westminster election in Northern Ireland was notable for the lack of attention which was paid to the finer details of the Protocol. The pro-Remain parties (Green, SDLP, Sinn Féin, and Alliance) focused on supporting the campaign for a second referendum or outlining their objection to any form of Brexit for Northern Ireland.

The SDLP did not directly refer to the detail of the Protocol in their manifesto, but promised to work towards revoking Article 50, and voting “against any attempt to introduce a customs or regulatory border across Ireland.” Alliance gave the Protocol slightly fuller treatment in their manifesto. They said they would advocate for “a wider future economic relationship for our region beyond the terms and scope of the current Ireland/Northern Ireland protocol.” Sinn Féin maintained “there is no good Brexit. The Tory government and the Westminster parliament created Brexit. There is no British or Westminster solution to Brexit. The Irish solution to Brexit will only be found in Dublin and in Europe.”

Reality sets in. Views going forward

While Northern Irish parties’ views on Europe can be characterised as “shifting,” it is also important to remember there have been periods of stasis too. 2020 proved to be such a period. As the behind-closed-doors negotiations between the UK and EU played out, COVID-19 took over as the burning political issue at Stormont. The Protocol did come back onto the political agenda towards the end of the year through the short-lived provisions in the Internal Market Bill which would have broken international law in a “specific and limited way.”

For the Remain parties, this was an affront by the government which deliberately used Northern Ireland as a bargaining chip in the final stages of negotiations. For unionism, the provisions were welcome, but did not go nearly far enough. Aside from that foray, the parties were not given much opportunity to formulate policy with regards to the ongoing negotiations. Blanket unionist objection to the Protocol continued throughout 2020, and nationalists/remainers simply presented it as the least worst option available, especially if there was a no-deal end to the negotiations.

Come the end of December 2020, the reality of the Protocol’s provisions began to set in. The UK and EU had reached an agreement on implementation, and the UK dropped the offending clauses from the Internal Market Bill. A no-deal exit was also avoided on Christmas Eve, though information to businesses on the front line of trade across GB-NI was still being sent on December 31st.

The unionist parties continued to warn throughout December that the Protocol would not only undermine Northern Ireland’s constitutional position but would lead to profound economic complications for the flow of trade and goods across the Irish Sea. The Remain and nationalist parties did not dispute this but argued the DUP “own goals” over Brexit was what had led to this point.

In both Westminster and Stormont, those parties continued to oppose Brexit, including the deal negotiated with the EU on Christmas Eve. They did, however, continue to support the full implementation of the Protocol, and the SDLP have argued it paves the way for closer all-island economic cooperation. Together with Alliance, the SDLP will likely want to protect the Protocol arrangements against any attempts to undermine it.

Sinn Féin have continued to stress the need for a border poll to provide an opportunity for Northern Ireland to regain its full place in the European Union, via a united Ireland. Galvanised by increased support in the Republic of Ireland’s election last year, Sinn Féin will likely continue to put EU membership front and centre of this campaign, despite their Eurosceptic past.

First Minister Arlene Foster has at times tentatively sought to portray the positive potentials for the Northern economy, and the “gateways of opportunity” that exist. However, both major unionist parties called for the triggering of Article 16 of the Protocol in order to suspend elements of it, in response to the difficulties supermarkets and other industries have experienced in the first few weeks of January importing to Northern Ireland.

What effect such a move would have in reality was not entirely clear and turning back the clock on the Protocol appeared very unlikely. However, the EU’s brief flirtation with triggering that clause themselves at the end of January, in order to prevent COVID-19 vaccines from leaving the block, brought Article 16 to the world’s newspaper headlines. It united the UK and Irish governments, along with each major party in Northern Ireland, in opposition to the move. Unionists claimed it revealed the duplicity of the EU position on the Irish border, while the nationalist parties and Alliance demanded the idea be withdrawn.

Each party’s position on Europe has clearly shifted and adapted over the decades. They have also been evolving since 2016 too. The latest episode with the Protocol demonstrates that the issue of Europe for Northern Ireland will remain a volatile debate. However, a period of stasis for the parties’ respective positions could be on the horizon. It is worth remembering that this story is much older than the 2016 referendum, and worth preparing for the likelihood it will dominate politics well beyond 2021.