As more survivors of the Troubles come forward to tell their stories, the question may be raised of how those who lost loved ones are represented in the media, how they represent themselves, and what their stories represent within the larger story – both then or, more particularly, now.

I have just seen two powerful recent portrayals: Colin Davidson’s Silent Testimony, on show in the redeveloped Ebrington barracks site in Derry/Londonderry, and The Life After, a documentary made by Brian Hill and Niamh Kennedy for Century Films, shown at Curzon Bloomsbury in London last week and followed by a Q&A with the co-directors.

Artist Colin Davidson pictured at the opening of his exhibition ‘Silent Testimony’ in the Nerve Visual Gallery, Derry/Londonderry (Photo credit: Nerve Centre).

Silent Testimony is in Nerve Visual, the gallery now occupying the sleek space created for the 2013 Tate Turner Prize and showcasing art and photography about the conflict. Davidson’s eighteen extra-large portraits – eight men and ten women – fit perfectly into the two hushed darkened rooms. They are unflinching and deeply intimate – we may start at a respectful distance, but then are drawn to examine them more closely, engaging far more intensely with the faces than we would ever do in real life. Only a couple of the women look directly at the viewer; most cast their eyes down and to the side, as if protecting themselves from our gaze, withdrawn into a private world of memory, trauma and grief. They appear as ordinary as ‘those we pass on the street’, but they are made extraordinary by their experience of having been bereaved by the Troubles.

Those soft and clear eyes are the heart and soul of each portrait, painted photo-realistically, while the rest of the portrait is moulded, gouged, pasted and scratched around them, with a vast range of tools, techniques and colours. Each picture has a short caption telling only the relationship of the sitter to the victim, their name, and the date and circumstances of the death – but not the religion of the victim or any details about the perpetrators.

A few spark my interest just now. Virtue Dixon, whose daughter Ruth was killed on her 24thbirthday in the Ballykelly Droppin Well bombing, also appears in The Life After. Walter Simon’s son Eugene’s body was discovered in a County Louth bog; his story is the basis of The Ferryman, Jez Butterworth’s award-winning play – itself a fascinating take on memory and trauma. In one eloquent detail, we are told that Paul Reilly sat for his portrait in the bedroom of his daughter Joanne, killed on 12 April 1989, “kept exactly as she had left it that day. The clock is stopped at 9.58 am, the time of her death.”

‘Silent Testimony’ was previously on display at the Ulster Museum (Photo credit: Michael Foley, originally shared on Flickr)

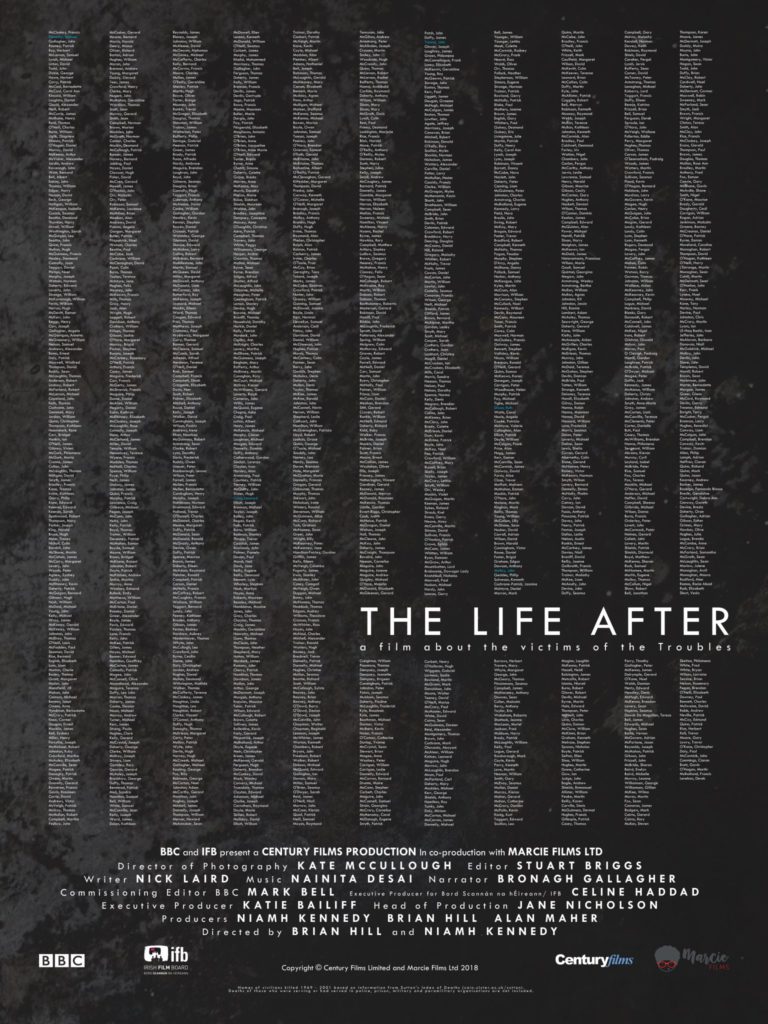

The Life After was made by co-directors Niamh Kennedy and Brian Hill. It interweaves archive footage of the Troubles, starting from the civil rights marches in Derry, headshot interviews with relatives, mostly women, of five who died in the conflict. Like the Davidson portraits, the faces are shown in raw, extra-large closeup and the interviews are visceral and intimate.

We meet Sharon, whose brother Winston Cross was abducted and murdered by the IRA on 11 November 1974, Collette, whose father was beaten to death by the RUC in the family front room, Virtue Dixon, whose daughter Ruth was killed in the Ballykelly bomb, Marie, whose husband was killed by loyalists as he tended bar in his pub, and Pat and John Molloy, whose son was murdered by loyalists as he walked home from an evening out.

The film is accompanied by a soundtrack of ominous, haunting music and – its most original feature — poetry by Nick Laird, sometimes read by the participants, sometimes by a narrator. It was not clear until the Q&A afterwards that Laird had been given the interview transcripts, from which he then wrote prose poems, which were then approved by the interviewees themselves.

These films are hard to watch; the pictures are hard to see – tissues are provided in the galleries. The interviews are hard, indeed deeply draining, to carry out, I know from my own work – it feels as though we are, if only for briefly and futilely, sharing in carrying the load. This is – yet another – both/and scenario. I utterly affirm the participation of these women and men – I know that they find it helpful to retell their stories, to be heard: “We have had to deal with it ourselves. It’s very important people know. We need to talk about it.”

Beyond question is the bravery and integrity of those who allow themselves to be interviewed for TV, film and press, or indeed to be painted. They have been invited from highly regarded organisations such as WAVE Trauma, and Unheard Voices in Derry/Londonderry. They are “allowing” and while they do not have much if any control over the creative process, they do have the right to block their inclusion in the final product.

At the same time, I want to be able to raise critical questions about how the narrative is being told and to what end. Each of these individual stories is an intensely unique and personal story, demanding to be valued as such. And these stories must together point to patterns and present day systemic realities affecting perhaps tens of thousands of Northern Ireland’s citizens as well as the whole of society.

From the cinema audience, the point was made, almost innocently – “it feels very recent still.” Yes, of course, this is the point about trauma. For those who have lost loved ones, and in most cases have not achieved any justice or closure, time, like that clock, stopped still. Yet their faces show the marks of time having past. This those of us who are close observers have come to expect and take for granted, that when victims tell their story, they recount it in graphic, technicolour detail, as if it happened yesterday.

It is a staggering reality that these tragic events happened thirty, forty, almost fifty years ago. There was no official response to victims and survivors until 1997, almost thirty years after the first deaths, when the first Victims and Survivors Commissioner, Kenneth Bloomfield, was appointed and published a report the following year. At the Peace and Beyond conference held in April this year, the current Commissioner, Judith Thomson, said, without irony, about levels of trauma, transgenerational trauma, poverty, deprivation and educational disadvantage: “Twenty years after the Agreement, victims and survivors still haven’t had their needs met. We can’t pretend it will be easy. We need to start the journey now.” Start the journey now?

We are in the midst of a flurry of films about the Troubles. There were the three films entitled Survivors, each of which featured two men and one woman, shown on BBC One Northern Ireland in January this year. There was the insightful and reflective Patrick Kielty documentary My Dad, the Peace Deal, and Me, shown on the BBC on 4 April this year. Both The Ballymurphy Precedent, on release now in selected venues – and to be shown on 1 August during the Féile, and Unquiet Graves, about collusion and the Glennane Gang, due out in September, explore the role of British state forces in killings in the Troubles, No Stone Unturned (2017), about the Loughinisland Massacre.

There is no shortage of films being made. The question remains, however, how many people get to see them, and whom do they influence? The Curzon was packed for the single showing of The Life After last week – perhaps because of the Q&A; but there were only a dozen present when I went to one of a handful of London showings last autumn of No Stone Unturned. Rarely – the Patrick Kielty programme was shown on BBC One – are the documentaries shown on mainstream British TV.

To my mind, The Life After focusses too much on the violence and on clichéd archive footage – although any British audience under the age of 40 would have little or no knowledge of the Troubles and might find the historical approach informative. One audience member from Northern Ireland points out that the film lacks contemporary context; Brian Hill mentions Brexit – but there is plenty of unfinished business from the Troubles, regardless of Brexit, much of it trauma related. “The level of trauma in Northern Ireland shocked me to the core,” admits Niamh Kennedy.

The directors are asked, inevitably, about being outsiders. Brian Hill responds that it’s sometimes better and easier for an outsider, who’s not mired in the local politics, to do useful work. He adds: “There’s a really worrying trend, that only certain people can tell certain stories, and that’s nonsense.”

Niamh Kennedy explains they did not set out to make a film about women, but found that women are much better at expressing themselves. The story of the Troubles is heavily gendered. 91% of victims were men (just as 75% of the 4,500 who have died by suicide since 1998 are also men). Women, as Kennedy points out are “the ones left picking up the pieces.” Men tell a story of violence and blame; women tell a story of how their families were before the event, the impact on family and children, of doors being kicked in by soldiers and invasions of domestic space.

Brian Hill is asked in the Q&A explicitly about his motivation and again, even more explicitly, “What is the impact you would like to make with the film?” He replies, not entirely convincingly, “It’s about the futility of violence.” I’m a little disappointed by this worthwhile but rather vague and grandiose ambition. There are many more prosaic legacies of the Troubles that need to be changed or fixed, including the levels of suicide, mental health and addiction.

Often what is not said or understated is as important as what is explicit. The film deliberately chooses only ‘innocent victims’, those caught in the wrong place at the wrong time, as does Silent Testimony. One of The Life After victims was killed by the RUC and one of the Silent Testimony portraits was the relative of a victim of the B Specials; another was a 13-year old IRA member shot by the British Army. These representations are not really neutral – they conform to established genres and the master narrative – and it is a ‘master’ narrative – about the Troubles – mutely reinforcing, for example, the notion of a “hierarchy of victims” or ambivalence about victims of the British Army. And they do not say enough about the systemic, present day reality of trauma and its effects on younger generations.

- Silent Testimony is on at Nerve Visual Gallery, Derry/Londonderry until 16 September. Beyond art and photography, the Gallery’s programme explores Northern Ireland’s ‘Spirit in ’68‘ and the broader international context.

- Colin Davidson will take part in a talk at the Nerve Centre on 13 September. Click here to register.

- There are scheduled screenings of the Ballymurphy Precedent.

- No Stone Unturned: The Loughinisland Massacre is available on Amazon Prime.

- My Dad, The Peace Deal and Me with Patrick Kielty is available on YouTube. Click here for articles on Northern Slant mentioning this documentary.

- The trailer for Unquiet Graves is available here. Release dates are being posted on Facebook.