Do apologies and corrections matter less, or more than ever? And can someone ever really apologize properly in 140 characters?

Of the many adjectives applied to President Trump, one that’s frequently used is “unapologetic”.

That such a description has been embraced by his supporters as a positive, a defining characteristic of strength, is indicative of how a balance has shifted in our civic discourse; away from humility and responsibility and towards bluster, bombast and supreme self-confidence.

As the president leaves a chaotic G7 summit in his wake (and, really, could Vladimir Putin have dreamt of ending up with a more beneficial outcome?) and heads into the ratings-driving part-summit-part-circus with Kim Jong-Un in Singapore, the last thing anyone is expecting – and literally nothing by now could be truly unexpected – is that Trump or anyone around him might ever acknowledge that he may be wrong about anything.

Indeed, the very idea of apologizing has been turned into a trope of political weakness, where acknowledging a mistake or making a gesture to encourage compromise is now derided as somehow un-American. It’s all part of what Paul Krugman called the “epidemic of infallibility.”

Two high-profile apologies in the US this past week helped throw the spotlight on what it means when missteps, malice, or poor judgment happen in the modern public gaze.

Amid the row over the president’s decision to disinvite this year’s Super Bowl champions the Philadelphia Eagles from the traditional White House reception, Fox News used an image of Eagles players kneeling on the turf, suggesting that they had been taking part in the widespread player protests against social injustice which had so angered the president. In fact, they had been praying before the national anthem began. Social media users – including some of the team themselves – were quick to point out that no Eagles players had protested in this way during the season. The next day, Fox apologized for the error – twice – and deleted the segment on its Twitter feed.

Amid the row over the president’s decision to disinvite this year’s Super Bowl champions the Philadelphia Eagles from the traditional White House reception, Fox News used an image of Eagles players kneeling on the turf, suggesting that they had been taking part in the widespread player protests against social injustice which had so angered the president. In fact, they had been praying before the national anthem began. Social media users – including some of the team themselves – were quick to point out that no Eagles players had protested in this way during the season. The next day, Fox apologized for the error – twice – and deleted the segment on its Twitter feed.

The players, though, were angry; some calling the move “intentional and strategic” and “propaganda” while attacking Fox for “carrying his [Trump’s] water to sow division.”

Was it an honest, or lazy, mistake in image sourcing, or a malicious use of visuals that left viewers with the requisite impression to back up the president’s dubious assertions about the Philadelphia team? The apology didn’t say how the error occurred, just that the network regretted it.

Even though the content was verifiably wrong, the damage had arguably been done. What matters in this particular instance was that the players pushed back to bring the apology from the network (and you have to ask, obviously, if it would have been forthcoming if they hadn’t got involved). But for those who had already seen it as part of Fox’s coverage of the story, it likely reinforced their opinion of protesting NFL players in general and therefore why viewers might believe President Trump has been right to take them to task.

One of the Eagles players, Zach Ertz, who had spoken out about the incident, subsequently said: “I feel like our community right now is either on one side or the other and in my opinion our country should be trying to build up everyone. It’s not my job to beat down my opinion over anyone else and vice versa… People should try and get the facts right and not try and skew it one way or the other… When I make a mistake on the football field, I learn from it and get better and that’s what I hope everyone does.”

At the other end of the political spectrum, comedian Samantha Bee found herself at the eye of a storm after using her TBS show to aim what was certainly a vulgar insult at Ivanka Trump. Bee apologized on Twitter and then used the opening segment of her next show to again acknowledge that she had overstepped the line.

Sam addresses the controversy from last week's show. pic.twitter.com/RtqBOhOCVf

— Full Frontal (@FullFrontalSamB) June 7, 2018

Bee’s on-air apology also expressed regret that she had distracted from debate about really important issues – the original segment was intended as a comment on the government’s immigration policy. Almost immediately and inevitably, the row over Bee’s remarks became conflated into the partisan whataboutery surrounding actress Roseanne Barr’s apology for a racist tweet which had resulted in her show being cancelled. Sadly, in our echo chambers, there is usually always something else to point to which provides a measure of exactly how fulsome an apology should be, or what consequences should await any transgressor.

In The Atlantic, David Frum wrote that “The antidote to Trump is decency” and argued that the moral high ground was still worth striving for, but it requires restraint.

“Donald Trump and the political movement behind him are empowered by ugly talk.

“Their own talk stands out less sharply in contrast. “You did it first … you did it worse … you do it more” are accurate enough answers, but they are not as powerful as not doing it at all.

“Let Trump be Trump. Let decent people be decent.

“Trust your country – not all of it, sadly, but enough of it – to notice and appreciate the difference.”

The Age of Outrage

While we may have passed into a zone where as a society we don’t always work from a shared set of facts, for apologies to mean anything we need to operate from a shared sense of what is right and wrong – in effect, we need to have a roughly equivalent concept of what needs to be apologized for.

What the Fox and TBS incidents have in common is that they highlight just how divisive America’s “culture wars” have become, and how partisanship has skewed any shared sense of what is acceptable and what is not – or at least made it almost impossible to have that kind of discussion, assuming anyone even wants to anymore.

And it’s no coincidence both incidents directly involved the President of the United States, who dived into the Twitter debate with gusto, knowing it would stoke the fire under his base.

Where apologies still mean something, it’s usually to those for whom they always did. But for others, the words can be as insignificant as another throwaway line in a soundbite; worse still, they’ve become just another part of the political game.

In the era of Donald Trump, for whom every interaction – either personal or on behalf of the nation he purports to lead – appears to be a contest, that divergence has accelerated. If you’re not winning you’re losing; and if you’re admitting you were wrong, you can’t by definition be winning. Ergo, apologies are for losers.

Margaret Renkl writes at the New York Times on how the strategy of apology has changed in what she calls The Age of Outrage. Once someone publicly displays their poor judgment, she writes, “That first round of fury is followed swiftly by more fury as new voices defend the pilloried one. Tweet something stupid, and it must follow as the night the day that Twitter will erupt with partisan howls on every possible side, right on up to the aggrieved tweeter-in-chief.”

And she argues, reasonably, that the instantaneous verdict demanded by Twitter and the inevitable way it forces people to take sides doesn’t allow genuinely remorseful people to express how regretful they may actually be. And that’s why Samantha Bee’s follow-up on-air apology gave context to the incident in a way that Twitter never could, or why in some of the #MeToo cases, an apology was only ever the beginning.

It has long been the case where what we’ve come to recognise as a standard public political apology has been watered down to the extent it would contain the requisite “sorry if anyone was offended” – as did Trump’s initial response to the infamous Access Hollywood tape. Increasingly though, you might be forgiven for believing that when political apologies happen these days, they’re more “I’m sorry I got found out…” than “I’m sorry I did it in the first place.” But essentially they’re mostly “I’m sorry you’re upset about this.”

The UK government’s handling of the Windrush scandal may as well have been a case study in how not to acknowledge an error, take responsibility for it, and control the news agenda. And while I want to keep the focus of this piece on the US, it is absolutely worth pointing out that the art of a personal political apology is, thankfully, not dead; witness Justin Trudeau – yes, the same Justin Trudeau that Trump is now going after to cover for his G7 tantrum – apologize to Canadian LGBT citizens last year.

Mending the media’s mistakes

In the contested dialogue between press and politicians, there is more at stake than ever for the media in swiftly and effectively correcting a mistake; since either way it will provide ammunition for opponents all too ready to jump on any missteps and extrapolate them as normal practice to undermine every element of coverage they don’t like. For example, when NBC got a significant story wrong about the president’s lawyer Michael Cohen being “wiretapped.”

Trump was quick to react:

NBC NEWS is wrong again! They cite “sources” which are constantly wrong. Problem is, like so many others, the sources probably don’t exist, they are fabricated, fiction! NBC, my former home with the Apprentice, is now as bad as Fake News CNN. Sad!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 4, 2018

“You have to be perfect,” said CNN’s Amanda Carpenter on Reliable Sources, “and that’s not a bad thing since it challenges all of us to be better.”

As long as there is journalism there will be mistakes. Other recent examples of apologies by individual journalists have taken many forms, and allow them to contextualize their regret as they wish; from CNN’s Anderson Cooper apologizing for a “crude remark” in an interview with a Trump spokesman, to MSNBC’s Joy Ann Reid’s strange apology for blog posts apparently a decade old, to Fox Business’s Charles Payne’s explanation on Twitter and on-air for something a guest said about Sen John McCain that Payne said he “didn’t pick up” during a live discussion.

— Charles V Payne (@cvpayne) May 10, 2018

But as if to illustrate the speed at which the news cycle turns, the remarks on Payne’s show about McCain were, of course, soon dwarfed by those by White House aide Kelly Sadler. Obviously there’s a discussion to be had on the extent to which political figures are responsible for apologizing for others, in their party or on their staff, for things that are said on their behalf.

But what happens when politicians don’t apologize, simply because they don’t think they need to?

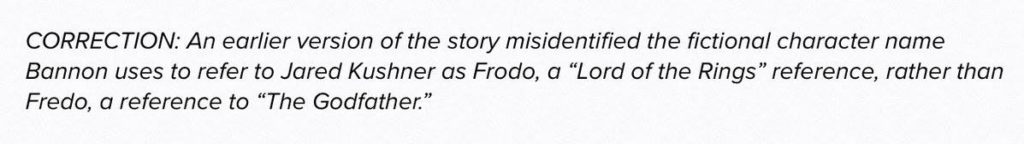

In the case of the Trump administration, the approach seems to be to simply brazen it out; knowing that the next, distracting, thing, whatever it is, is just around the corner. Meanwhile, it’s inevitable that plenty of things fly under the radar. You may have missed a rather important correction recently – what David Frum called “the sort of correction that starts wars”.

Note, a correction, not an apology.

Which raises the simple question, does this president and this White House ever apologize for anything?

Jay Willis wrote at GQ in February that, “To the president, admitting to a mistake is tantamount to weakness and failure, and his underlings have already learned to follow his example… If any limits exist to the types of despicable conduct these people will defend, we have yet to find out.”

In such an environment, therefore, it’s even more important for the press to acknowledge its errors and own them.

Sometimes the corrections can be as popular as the original story – and even generate follow-up traffic – like this one from Politico:

But in all seriousness, perhaps the most significant media apology of recent months was the one issued by ProPublica for an article it had published the previous year about Gina Haspel, now the head of the CIA. The story had been given fresh legs after Haspel’s nomination, and with the news organization having built its reputation on attention to detail and its position as a trusted source, any mistake they might make, along with the wide circulation of the story, would be highlighted more than usual.

While important elements of the story were accurate, others were not, and ProPublica recognized the potential hit to its credibility, and moved to delete tweets featuring the uncorrected story, while Editor-in-Chief Steve Engelberg issued a nearly-1,000 word statement which CNN media correspondent Brian Stelter called a “model for transparency.” The statement concludes:

“We at ProPublica hold government officials responsible for their missteps, and we must be equally accountable. This error was particularly unfortunate because it muddied an important national debate about Haspel and the CIA’s recent history. To her, and to our readers, we can only apologize, correct the record and make certain that we do better in the future.”

Addicted to access?

According to the Washington Post, the president could be on course for a staggering 10,000 misstatements of fact by the end of this term.

Set that statistic against the fallout from the recent White House Correspondents’ Dinner, when those who are supposed to be holding the administration to account couldn’t decide whether they should apologize to press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders after some complaints about comedian Michelle Wolf’s routine, or to their own members for criticizing Michelle Wolf.

Veteran ’60 Minutes’ reporter Leslie Stahl recently spoke of what Trump had told her about why he attacks the media the way he does. “He said you know why I do it? I do it to discredit you all and demean you all, so when you write negative stories about me no one will believe you.”

But as Nicholas Kristof pointed out in the New York Times, while the media at large continue to be “addicted to Trump” in what is effectively a symbiotic relationship, things are unlikely to change anytime soon. “News organizations, especially cable television channels, feed off Trump – like oxpeckers on a rhino’s back – for he is part of our business model in 2018. As long as our focus is on Trump, audiences follow.

“It’s not optimal to have as president an authoritarian who denounces journalists as enemies of the people, but he has given us a sense of mission and a ‘Trump bump.’ Every time he denounces us we get more subscriptions.”

Finally, Trump’s approach to the presidential pardon power may have arguably devalued the ultimate acknowledgment of sincere public regret, all to advance the quixotic narrative of his presidency. And yet there seems to be no end to the surprising list of recipients as this type of behaviour becomes commonplace.

As Gary Younge writes in The Guardian, America is “normalizing” Trump.

“Those on the right,” Younge says, “trading principle for pragmatism and the certainty of aggravation for the possibility of access, accommodated, adapted and soon fell in line as though the line were their idea.”

And by normalizing this President’s day-to-day behaviour, by failing to attach consequences to political discourse that has destroyed established norms, we’re effectively normalizing what is likely a permanent shift in our relationship with the truth.

So, to partly answer my own question; I think we’re at a place where corrections and apologies certainly matter to – most of – the media since, no matter how many times someone screams “fake news”, reputation remains their stock-in-trade; and a regard for keeping the record straight is, for now at least, still one of the elements by which they are judged. For politicians, on the other hand, it seems more true than ever that people almost expect them to dissemble, and there are usually relatively limited costs and consequences when they do.

On one side of the press-politics equation, therefore, for many news organizations – at least those who still value the currency of credibility – saying sorry is more important than it was even a few years ago. On the other side, the political power of genuine remorse appears to be dwindling further every day.

Perhaps that imbalance is now permanent, just part of the new normal.

As Ryan Bort wrote last year in Newsweek, while Trump rarely apologizes, he is quick to demand apologies from others he feels have slighted or attacked him. For Trump, Bort writes, “apologies are not about coming to any sort of mutual understanding; they are about wresting power away from adversaries. He has very little chance of actually getting it, but by asking for it publicly he feels he can create a perception that he is owed something. It’s a final, feeble attempt to secure the thing he desires more than anything else: respect.”

Flashback to a rally in North Carolina in August 2016; when Trump came as close as he may have come, in his time as candidate or president, to apologizing; when he made this non-specific, blanket statement:

“Sometimes, in the heat of debate, and speaking on a multitude of issues, you don’t choose the right words or you say the wrong thing. I have done that, and believe it or not I regret it… particularly where it may have caused personal pain.”

He went on: “I’ve traveled all across this country laying out my bold and modern agenda for change. In this journey, I will never lie to you. I will never tell you something I do not believe. I will never put anyone’s interests ahead of yours.”

Promises kept?

Also published on Medium.