Every so often it’s healthy to reflect on where things are and where they are going. At Northern Slant, we want to promote a conversation as to how Northern Ireland can ‘rethink’ certain approaches to policy and decision-making. What can we do differently? What can we learn from elsewhere or from emerging research? In this article, Ryan Hogg considers how we can rethink wellbeing and economic growth.

Northern Ireland is ‘happy’. Recent findings by PwC add robustness to ONS statistics that consistently rank NI top of the UK in terms of happiness and wellbeing, and lowest in terms of anxiety. This would place Northern Ireland as the happiest region in the 13th happiest country in the world, according to the UN. This likely comes as a surprise to a significant proportion of the NI public, and no wonder.

Northern Ireland is ‘happy’, so why doesn’t it feel like it?

Certainly, relative expectations and standards of happiness play a part in Northern Ireland’s continuous topping of the table. Intergenerational trauma and a troubling record on suicides indicates something closer to this effect. Since Northern Ireland is the only part of the UK to have emerged from an effective civil war, it may improve its citizens’ appreciation for life in general, regardless of conditions. Add that inference to other indicators of poor mental health and we begin to paint a picture of a region that either views its happiness in relative terms, or refuses to confront trauma. Whatever it is, frustration is surely brewing.

That’s because indicators that suggest a festering of discontentment are easy to find: average wages are barely above 2010 levels when adjusted for inflation; home ownership, particularly among the young, has been on the decline for longer, with young renters next in the firing line; and as much as leaps forward appear to have been made, city centres remain overrun by monotonous, low-skill jobs masquerading as FDI. And while NI might be polled as the best place to live and start a business, a consistent outward flow of graduates ultimately suggests otherwise.

We may ask how long it will take for the intergenerational and expectation effects to wear off, and Northern Ireland as a society is left asking why it should settle for less. If the current system, geared as it is to economic growth, is complicit in producing those outcomes and ensuring NI drifts further from the UK average, it is worth asking what a different, wellbeing-based approach might achieve.

Changing tack

Reducing the dependence on GDP (Gross Domestic Product) as a measure of societal and individual progress would be a start. When GDP grows faster than a population, living standards are said to increase. However, the measure is becoming less person-dependent with the rise of automation and tech-driven FDI, while the growing relationship between GDP and inequality in the last 40 years indicates disproportionate ‘wellbeing’ improvements for increasingly fewer people under the measure.

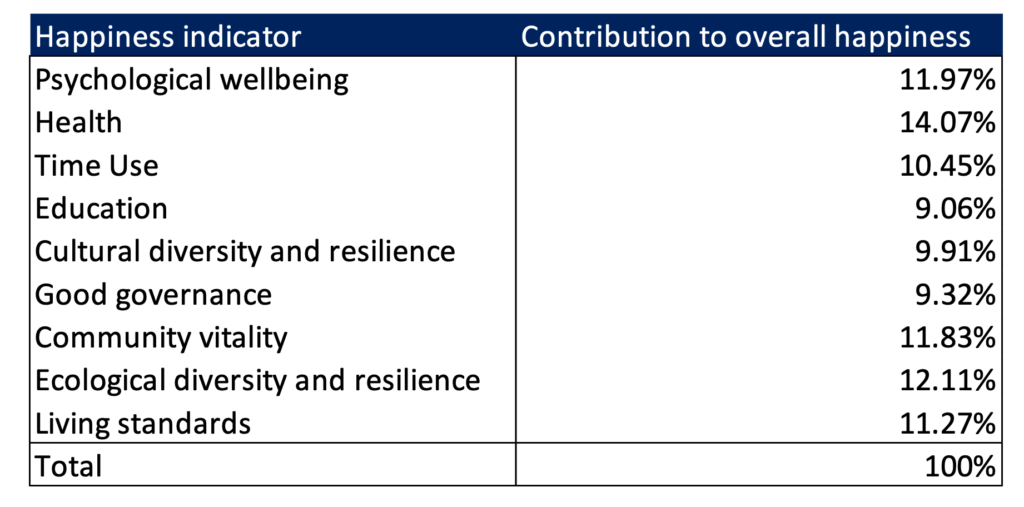

Instead, we may have more success viewing output as a consequent variable of other strategies. We can look to Bhutan, for example, where the main indicator of progress is Gross National Happiness (GNH), rather than GDP. Rather than relying on people’s subjective survey responses, GNH is an aggregated measure made up of multiple variables, with Psychological Wellbeing, Health and Time Use making up more than a third of overall happiness. Income per capita, the main indicator of wellbeing in developed economies, makes up about 4% of total ‘happiness’ in Bhutan.

The consequent links that can be drawn from wellbeing to economic output are eye-catching. Naturally, happy citizens are more productive in work and wider society, while contentment is more likely to discourage brain drain among younger populations. And since Bhutan incorporated GNH into its national statistics, its poverty rate has declined rapidly.

On the other hand, Bhutan ranks low on international comparisons of happiness, suggesting an exaggerated emphasis on wellbeing can forget other indicators of progress – much in the same way GDP per capita neglects to inform us of other facets of a society. Yet it is difficult to argue with the basic intention of taking a broader perspective of the economic landscape.

Indeed, it may become necessary to our ultimate survival, thanks to the stubborn link between output and carbon emissions. As GDP per person increases, so too do emissions per person. The relationship is weakening, but not fast enough. Plus, the proposition of a degrowth model, of reinvestment rather than expansion, is gaining traction. Again, it is a policy unlikely to be taken up on a global scale, but it is another example of the momentum shift occurring in international economic policy over the last decade.

A chance to pivot

As with most of its policy considerations, Northern Ireland lives under the contextual constraint of being a small player, dependent on the actions of higher authorities. If the UK or Republic of Ireland stick to traditional policies over the next century, so will NI. But within those constraints are clear crossroads that the region can begin to take – whether it wants to lead on business or people; drive unbridled tourism or leave a cultural footprint; strive to rebuild the High Street as it once was or consider the growth of the circular economy in individual consumption.

After all, there must be something to the findings in those happiness surveys. Expectation of happiness is a powerful thing, and something the region should keep in mind as it looks to the future. Northern Ireland’s relatively low economic standing in comparison to the rest of the UK speaks to the nuance between GDP and happiness.

Northern Ireland is by no means poor, and we must seriously question how it can be made more sustainably happy. If GDP continues to be pursued primarily, we could expect NI’s wellbeing ranking to fall in the future. And while the measure shouldn’t be abandoned, it probably shouldn’t be the main indicator of progress either.

Fighting apathy, encouraging circularity and sustainability in individual and economic choices and producing a more holistic collection of indicators to policymakers would begin to turn the tide. Achieving economic growth, improvements to wellbeing and environmental sustainability will be a tough needle to thread, perhaps even an insurmountable trilemma. But it seems clear that attacking from the latter two first gives us the best chance. Perhaps in the not-too-distant future, reading surveys that rank Northern Ireland top in terms of happiness could be greeted with an unsurprised shrug, rather than a gaping mouth.

More in our ‘Rethinking…’ series:

- Rethinking: Healthcare by Roger Greer

- Rethinking: Mandatory coalition by Sean Haughey