In the year 1968, there were street protests and marches in Belfast, Berlin, Derry-Londonderry, Paris, Prague, Selma and beyond. Some of the most powerful captured images and video clips are on display at The Lost Moment exhibition at the Gallery of Photography Ireland. On the day of its launch there was a two-part symposium on the topic of “Civil Rights: Then and Now”.

The curator, Sean O’Hagan, who is photography editor at The Guardian, gave a guided tour of the exhibition. He explained his two-fold motivation: (1) that the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland was a precursor to the contemporary “Troubles”; and (2) his desire to address the lack of placing this campaign in the international context of other protests in 1968.

O’Hagan provided us insight on individual photographers and images. For example, David Hunn persuaded the police to allow him to trail behind a 1968 protest against American involvement in Vietnam — the result was a series with a fascinating perspective; David Newell-Smith’s images of unsurprisingly fashionable youth of the 1968 student protests in Paris; and the incredible story of first the smuggling of the photographs then the Czech photographer himself — Josef Koudelka’s pictures of the 2 August 1968 invasion of Prague by Warsaw Pact tanks.

“These photos have a lot of information in them, in addition to being a record of the time,” O’Hagan reminded us.

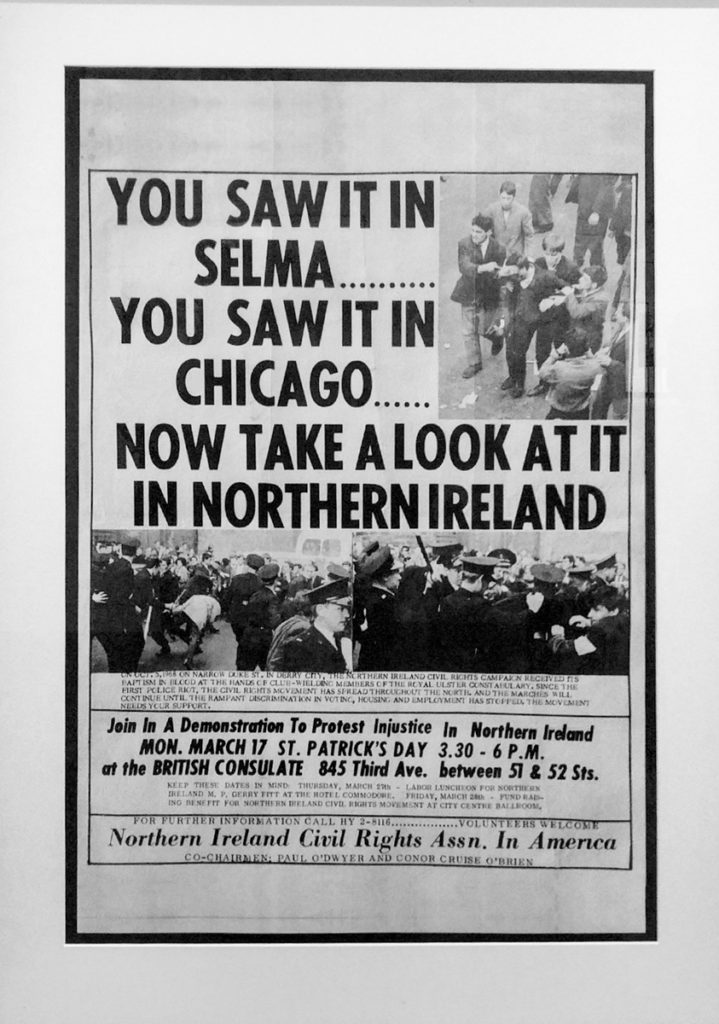

You Saw It in Selma. (c) Allan LEONARD @MrUlster

The final image in this international section is a poster: “You saw it in Selma … You saw it in Chicago … Now take a look at it in Northern Ireland”. O’Hagan explained the significance of this, in that key figures in the People’s Democracy and other groups went to the US to learn from its civil rights campaign; this image is a seque to the next section featuring Northern Ireland.

O’Hagan explained that every civil right march had its own atmosphere, which is reflected in the Northern Ireland images. They start as peaceful assemblies in town and city centre squares: provocative because such places were perceived to be bastions of Unionist rule. You can see the increase in tension and conflict as you progress chronologically.

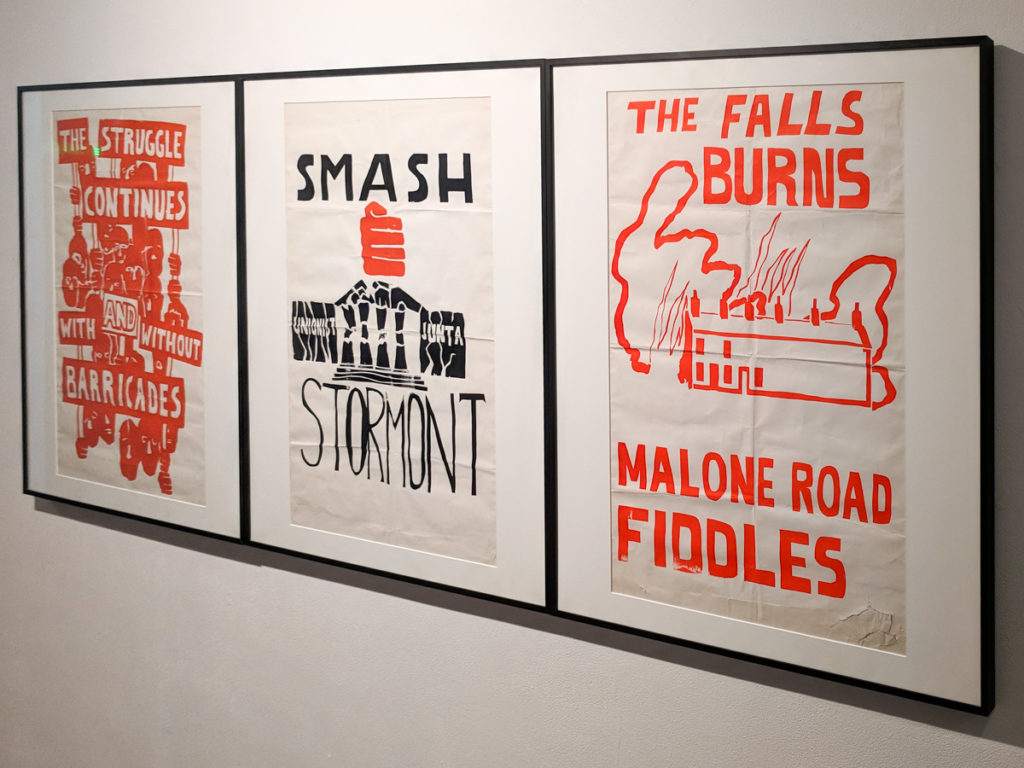

Inside some clear table cases is ephemera from both the civil rights campaigners as well as counter-campaigners, such as the Protestant Telegraph by Ian Paisley. There is also a small selection of posters, and O’Hagan explained their similarity with civil rights posters produced in other countries: “As the Troubles got heavier, a lot of people descended into Northern Ireland — French anarchists, Maoist Marxists. They were nicknamed ‘The Outsiders’, and they brought their imagery with them.”

The Struggle Continues / Smash Stormont / The Falls Burns. (c) Allan LEONARD @MrUlster

“Why 1968?” O’Hagan mooted. Two answers he suggested were: (1) young people not willing to be defined by the values or norms of an older generation; and (2) the effect of the Butler Act, which extended university education to Catholics, generating an increasing self-awareness of the injustices they saw.

The last exhibition section is entitled “The Lost Moment”, which O’Hagan described as optimism giving way by August 1969 to a “descending darkness”, with the “Battle of the Bogside” violence. An RTÉ Archives film footage loop shows a retrospective “Eye Witness” programme from 1979 and clips from various key events in Belfast, Derry, and Armagh. As O’Hagan argued, while the arrival of the British army was at first welcomed as a substitute for the lack of security provided by the RUC, the IRA convinced enough Catholics that it would protect them and progress their demands better.

Civil rights 1968/69

The first part of the symposium was chaired by Tommy Graham (Editor, History Ireland magazine), and included panellists Michael Farrell (solicitor and civil rights activist), Chris Reynolds (historian and academic), Sean O’Hagan (curator and writer), and Liam Wylie (RTÉ curator).

Farrell gave an overview of what conditions were like at the time leading up to the civil rights campaign, such as housing and employment discrimination. Eddie McAteer, as a former member of the Northern Ireland Parliament, once explained to Farrell the frustration of all but one Unionist member leaving the chamber whenever a Nationalist member rose to speak; this was a continual source of Nationalist frustration in Unionist-dominated Stormont. Likewise, former MP, Gerry Fitt, told Farrell that he repeatedly attempted to raise the issue of Northern Ireland in the House of Commons, but the custom at Westminster was not to discuss matters devolved to Stormont. More frustration.

Wylie provided a southern perspective, reminding the audience that RTÉ produced a programme ten years ago on the topic of 5th October 1968 (commonly referred to as the day that the Troubles began). For their online exhibition, he said that they were concerned that there wouldn’t be enough material in their archives, but discovered that there was — including the richness of recorded radio tracks.

Reynolds was asked what the common denominator was for all of the exhibition imagery. His answer was French: “Les année 1968” — the year 1968 in plural, which takes in all the societal upheaval that took place from 1965-1970s.

Indeed, Reynolds has spent much time in his academic career analysing the “transnational” dimension of the 1968 campaigns. He disagrees with the notion of 5th October 1968 as the seminal date, the exceptional narrative that the only significance of the civil rights campaign in Northern Ireland is as precursor to the Troubles.

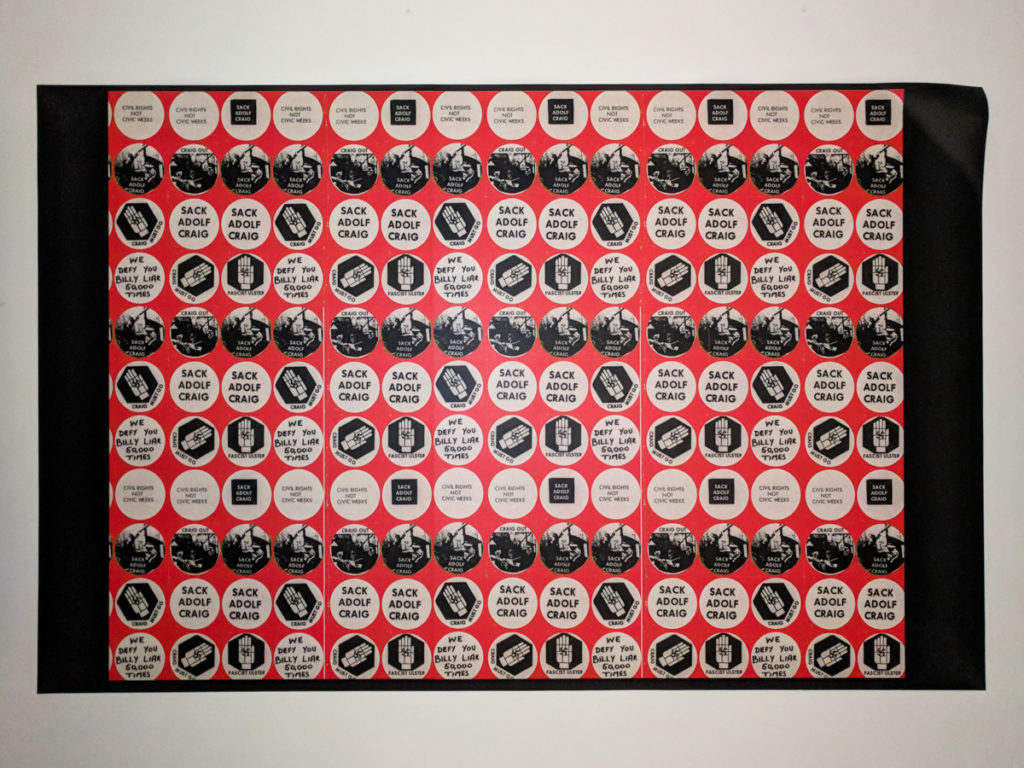

His book, Sous les pavés … The Troubles, compares the events between Paris and Northern Ireland. One interesting similarity with “SS RUC” chanted during protests in Armagh and Derry in November 1968 was “CRS SS” shouted out during Parisian protests aimed at French security services. On one of the exhibition walls are rows of stickers, including “Fascist Ulster” and “Sack Adolf Craig” (with reference to Northern Ireland Minister of Home Affairs, William Craig).

Sack Adolf Craig. (c) Allan LEONARD @MrUlster

There was some discussion on what “the lost moment” was, and what was lost. Some thought it meant what the civil rights movement lost. Others thought it was what unreformable unionism lost. Reynolds replied that the complexity of the civil right campaign in Northern Ireland was lost, as the aftermath exacerbated a more reductionist confrontation.

The panel was asked how social media would respond to such a civil rights movement today — would we sacrifice quality for quantity? Wylie replied that there is no shortage of material generated by social media for any event; it’s how it’s kept and put together that matters. O’Hagan saw social media as an effective form of organising activity, while stating that there isn’t yet agreement on the role of this form of citizen journalism versus established photojournalism. At least, he added, social media can serve as a counter to the contemporary omnipresent camera surveillance by the state.

A final question during this first part revealed the extent of sexism during the civil rights campaigns. Orla Farrell explained that fewer women took part in the student-led movements at the time, by the fact that there were fewer women enrolled as university students. And where they did get involved, some felt too intimidated to speak. A redress for People’s Democracy was to elect a “faceless committee”, which resulted in more women in leadership roles. Reynolds added the point that 1968 “was not a great day for feminism”, and subsequently led to the second phase of the women’s movement.

Civil rights in Ireland today

The second panel discussion was introduced by Declan Hayden (community development officer, Dublin City Council), chaired by Kitty Holland (social affairs correspondent, Irish Times), and included panellists Anthony Haughey (artist), Lauretta Igbosonu (migrant activist), Dragana Jurisic (artist), and Nigel Swann (artist).

Hayden remarked on the timeline of the exhibition images and how a worsening atmosphere reflected a huge fear of change in relationship with “the other”. His perspective is one of interculturalism, in contrast with multiculturalism: “Interculturalism means we weave things together, not living in cultural silos.” Hayden argued that far from diluting a dominant culture, inward migration can revive and save it. He gave an example St Patrick’s Day parades, from being a stale event “with a few floats and oranges” to a more vibrant celebration, and modifying Halloween celebrations, from being an American import to looking more at local historical traditions.

Hayden defined community as where we live and who we interact with — our neighbours, our shops. He also highlighted the role of mythology, rituals, and rites of passage: “Stories have in them everything that has happened, that has helped people form a sense of community.” For Hayden, he feels that the civil rights campaign needs to be reclaimed: “What do we need to fight for?”

Igbosonu told us of an improbable encounter with fellow panellist Anthony Haughey, who stopped on a busy road to help her with a flat tyre. We learned her story of migrating from Nigeria and how difficult the decision is to migrate: “You think people just say one day, ‘I think I’ll walk through the Sahara desert to see what’s on the other side’?” Igbosonu described her activism work with Haughey, including a postcard campaign where migrants at Mosney direct provision centre expressed what they want out of coming to Ireland, and why. She has also established a women’s group to support other migrants, yet also implored the rest of us to invite more new arrivals to participate in events such as today’s symposium.

On this theme of migration and immigration, Swann spoke of Presbyterian plantation in Ireland and subsequent exodus to America, as well as the influx of “the boat people”, Asian migrants who arrived post-Vietnam war. For his Borderlands project, he revisited the regions of the Ireland-Northern Ireland frontier. He discovered people with identities more malleable than one would assume. Swann pointed out that the introduction of the border with Irish partition split once united, local communities; Brexit may compel us to think what a reunification might look like.

Likewise, others commented on how partitionism became part of southern Irish culture, and that if there is to be a new Ireland, there will be a price, not solely financial but socially. Uncomfortable conversations will have to be had.

Haughey spoke of the role of culture and art in opening up civic discourse, which he defined as “socially engaged art”. He remarked that often in exhibitions you see the finished product, but “how do you show the complex process behind it?”. Complimenting this exhibition, Haughey said that its selection and presentation becomes part of the historical narrative.

Jurisic expressed a skeptical view of history, though. She said that three months after the fall of Yugoslavia, all the history books were rewritten: “I find fiction books more believable, in understanding how things were.” With new government policies in Croatia — such as being prohibited from officially describing oneself as “Yugoslav” — she is using her artistic talents “to recreate a more metaphysical reality”.

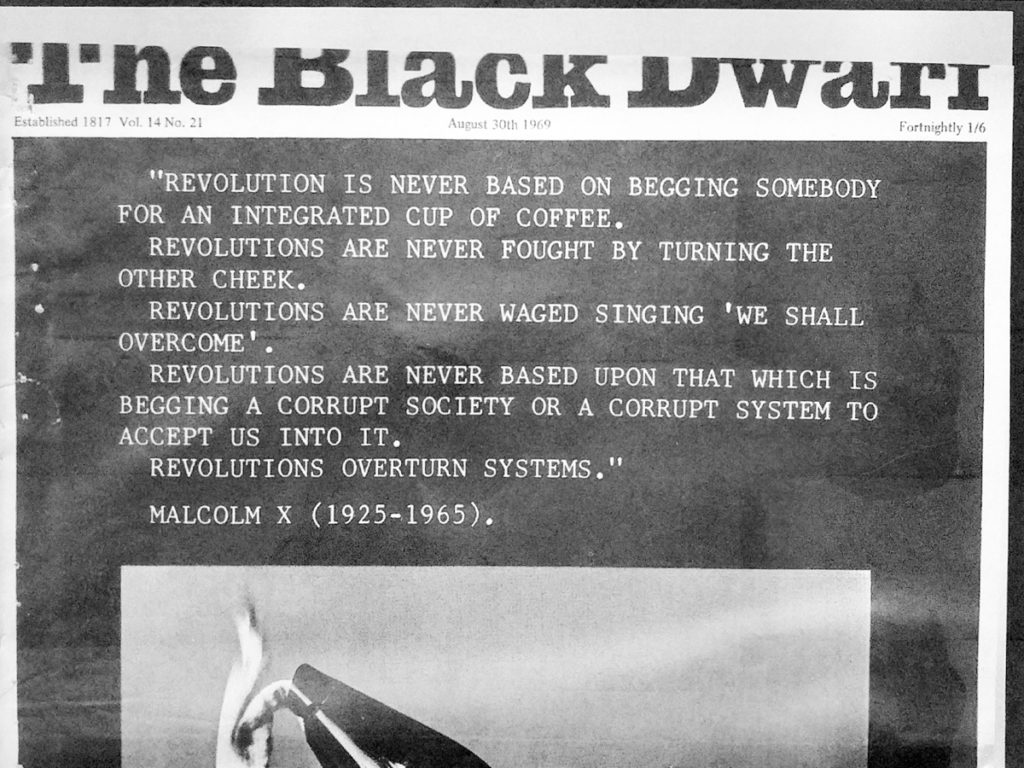

This opened up a discussion on identities and nationalism. How much they are self-defined versus being thrust upon you. How much is based on ethnicity versus social class. While there was much comment on the negative attributes of a national identity — Jurisic quoted comedian George Carlin on how could one be proud of something that you didn’t personally achieve — there were a few voices about the positive aspect of communal belonging. I suggested that not all nationalism is atavistic — you can have civic values in any society — but the question was what community are we developing. I noted that the panellists were sitting in front of images that included Martin Luther King, who I argued was an American racial integrationist, in contrast to Malcolm X, who is quoted in an exhibition poster: “Revolution is never based on being somebody begging for an integrated cup of coffee.” Be cognisant of identity politics.

The Black Dwarf magazine. (c) Allan LEONARD @MrUlster

Paul Mullan provided some hope by telling the audience of the work by the Heritage Lottery Fund (a funder for today’s event) as well as the Community Relations Council in Northern Ireland, on the programme series dealing with the decade of centenaries, which covered events on both sides of the communal divide. He also cited Conal Parr’s book on art and societal change in Northern Ireland.

Panellists debated points on access to the arts and the gatekeepers to its dissemination, whether it was governments or art professionals themselves. A counter argument was that with social media and the web generally, it’s never been easier to publish material. Yet Haughey underlined the role of agency:

“If you’re polemic, you stray into propaganda. It’s the process you work with and who owns it. Agency matters. You want engaged and active citizens.”

This was endorsed in the concluding remarks by Trish Lambe (Co-Director, Gallery of Photography), who promised more events such as this symposium, “to get us out of arts silos”.

Photo gallery

Originally published at Mr Ulster.