In February this year I wrote an article for Northern Slant on infrastructure and the important role it plays in the functioning of society. I argued it should feature much more heavily in the political discourse than it currently does.

It’s good to remember this issue isn’t something unique to Northern Ireland – governments across the world consistently miss spending targets for infrastructure with wealthy nations such as the United States and Germany today looking at the consequences of historical underspending. The importance of holding our politicians to account on this issue and making infrastructure a meaningful part of their discourse is paramount . Here again, Northern Ireland should be no different to anywhere else on that requirement and aspiration.

Energy is a fundamental subsector of this infrastructure world. It touches virtually every part of our modern lives, with a large impact on most household budgets. It therefore does often feature during election cycles, usually as a popular cry for lower prices for consumers, but not much more.

If we take this important sector though and distil it slightly further to electricity (energy also includes, for example, petrol, heating oil and so forth), we get reach electricity. The Irish electricity market, which is a single market across the island (the Single Electricity Market, or ‘SEM’) recently underwent some changes that will have some impact on everyone consuming electricity in the island of Ireland.

Within this context and building on the Institution of Civil Engineers’ #infra2018 campaign to have better conversations about our infrastructure (April was electricity month), it’s worth taking a moment to look at how the SEM works, why it’s important and why it should be a fundamental part of the political dialogue. The SEM is also held up as a strong example of all-island cooperation, something that has received much attention recently given Brexit and the 20thanniversary of the Good Friday Agreement.

General objectives for most developed countries are for the supply of electricity to be as secure as possible, as clean as possible and as cheap as possible. As such, the island of Ireland isn’t any different in this respect. The government in Dublin describes it as the “lifeblood” of the “economy and society”. The United Kingdom’s Electricity Market Reform is directed at incentivising investment in “secure, low-carbon electricity” and improving customer affordability. But how does that happen and are those three things complementary or are they mutually exclusive? What role does the SEM play in delivering these in Ireland?

As if that doesn’t already seem complicated enough, trying to decipher what the recent changes mean, how might Brexit impact all of this? Moreover, how does renewable energy and future policy choices in that respect fit in?

Understanding the system

The system will typically have one core source of revenue generation – sales to end users (commercial and retail). For different generation modes there may also be some revenue generated from a government-backed payment (e.g. for some forms of renewable energy – this is what was being paid under the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scheme). The rest of the cost base is then all the infrastructure required to create (generation) and serve (transmission and distribution) the electricity to end users, plus any fuel inputs required (wind is a free resource, but coal or gas has a market determined price) and operational expenses; so, part of the revenue stream will go to maintaining this infrastructure (e.g. to the grid operator) and part to the actor generating the electricity (e.g. the wind farm owner and/or operator).

It should be noted that there is much disruption either ongoing or expected to this model as more renewable energy and self (or home) generation enters the system (not so long ago the grid operator didn’t have to worry about homes sending electricity back into the grid), but as the model is broadly operating as is for now, we will keep focused on this more traditional model for the sake of simplicity. That should also act as a good base from which to understand changes and disruption, including the potential implications.

What’s the general shape of an electricity market?

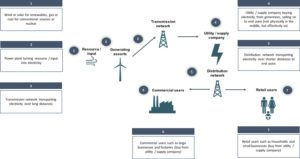

Developed electricity markets have broadly grown up around a common approach in which, at a high level:

- There are generating assets (think of Kilroot power station or a wind farm);

- Transmission assets (the large steel pylons that carry this are the usual visible manifestation – in Great Britain this is what is called ‘the National Grid’ – although this is also the name of a privately run company);

- Distribution assets (like transmission assets, but on a smaller scale – what connects your home to the wider grid); and

- Various substations and other connecting infrastructure that allow electricity to be delivered to end users.

Simplified, there is production, a means to transport electricity (transmission and distribution from hereon), and connection to the end users (homes and businesses – any consumer of electricity).

How does the electricity market look in Northern Ireland? What do people mean when they say there is an “all-island market”?

Since 2007 the Northern Irish electricity market has been part of the all-island system known as the SEM (Single Electricity Market). The SEM has operated effectively to date and is constructed around what is known as a “gross mandatory pool.

What this essentially means is that all generators over a minimum size are obliged to sell in to a centralised marketplace that is common to the whole island. This creates market price tension with the aim of lower cost producers of electricity being selected by the system operator (it is regulated and mandated to do this by respective governments). Suppliers (e.g. Power NI – the utility in the figure below) to retail users (e.g. a household) then buy electricity at the wholesale price from the pool. The additional costs seen on an electricity bill will, broadly speaking, represent the cost of transmission and distribution plus a profit margin for the supplier.

Although in theory the SEM is one market there are still physical constraints to the system physically doing functioning as such, despite upgrade works underway which will improve connectivity north to south (this has previously been a constraint in terms of sending electricity around the all-island grid).

The long-term aim is that power producers in any part of the island can sell in to the pool which suppliers to consumers (e.g. Power NI) then buy from. Although electricity is generally best consumed closest to where it is produced (to limit losses incurred when it is transmitted), once in the grid it is possible to conceive watching television in Antrim using electricity generated in Cork (although in reality the electricity in the grid is fungible and therefore cannot be separated like this).

What is the aim of all of this in an electricity market generally?

As with other developed electricity markets, the SEM wants to achieve a position of a steady supply that meets demand throughout the day, the with transmission and distribution networks capable of delivering smoothly and at the right capacity. In the context of the SEM (and other markets), this is where what are known as capacity payments play an important role.

Take making a cup of tea as an example; early evening, when you get home from work, just when everyone else is doing it. The system is going to experience a surge in demand and needs to respond to that, so there needs to be enough capacity (ability to generate electricity and availability to do so at that point in time) to meet this demand. But that’s not enough, because you also want some milk in your tea and you bought that yesterday, so it’s been sitting in your fridge overnight and all day, staying fresh. The reason it is fresh is that a steady supply has been ongoing all day.

So the SEM not only needs to ensure it can respond to peaks in demand, but it also needs to ensure that the supply is steady and unbroken throughout the day, for all users. If you think of how a water tap reacts when there is air trapped in the pipes, spitting and sputtering water, the electricity system can’t do this if appliances are to function correctly (and not have shorter lifespans). Nor would you want the situation that exists in some countries where peaks in demand result in some users having their electricity supply turned off to regulate demand.

How is that achieved and what does it look like from a Northern Irish perspective in the context of the SEM?

A House of Commons select committee, concerned with the impacts of Brexit on Northern Ireland, summed the SEM up as follows:

“It was designed to allow the small and inefficient energy markets on either side of the border to benefit from economies of scale. Generators on either side of the border compete to sell electricity into a common ‘pool’ from which homes and businesses draw their electricity. Those generators able to sell the cheapest electricity will have the most consistent demand whilst more expensive generators might find that they are only to sell into the pool at periods of high demand.”

To keep baseline capacity (i.e. the ability for the system to produce electricity on a constant basis) the SEM pays capacity payments to numerous producers that are selected in a competitive auction; that’s to say payments to incentivise actors to make and keep capacity available for a contractual period (there is no payment made if that is not done). This is done on a reverse basis, stating with the cheapest and keeps going until the desired capacity level is reached (the requirement is revised annually and complex modelling is carried out by the system operator to ensure there is sufficient security of supply without too much being paid for an excess of capacity).

In the 2017 auction (for supply in the 2018 year) there were 100 bidders, 93 of which were successful. This is a complex process and making it a commercial and operational success is dependent on having sufficient depth of expertise and experience residing with the system operator; something which is typically more feasible at a larger scale.

The most striking result from the 2017 capacity auction from a Northern Irish perspective was probably that Kilroot Power Station was not successful (i.e. it won no capacity). Much was made of this at the time, with concerns ranging from loss of jobs to security of energy supply for Northern Ireland. The loss of jobs is clearly an extremely important issue however it’s worth pointing out that Kilroot Power Station is an older and fully depreciated piece of technology that was expected to close in any event, largely due to clean air regulations, within the next few years. Whilst the shock of earlier closure is clearly very serious for many families earning a salary from its operation, this context is important in any analysis of the SEM’s impact.

Closure of Kilroot Power station may be deemed a negative consequence locally however competitive pressure, brings lower cost and more efficient generators coming online across the island, which benefits consumers. As part of the SEM, Northern Ireland is part of a much bigger market than if it was on its own (although the island of Ireland market is still small in a European context) and therefore can benefit from this enlarged competition. From the competitive capacity auction in 2017 Eirgrid estimates that around €200m of savings have been achieved on capacity payments alone.

A core point to be noted at this juncture is that as of today, renewable energy is not in a position to play the capacity role in the SEM and therefore fossil fuelled generators are relied upon. Whilst there will be times when renewable energy is able to produce the bulk of supply to meet demand, this isn’t always the case and when it isn’t available (e.g. after dark when there isn’t much wind) in which is why having contracted capacity provision is important, with marginal producers providing top-up as required.

In addition to capacity providers there are then what are termed “marginal producers” (a gas-fired power station could play this role) alongside renewable sources of electricity production. The payment mechanics for each are ultimately different with marginal producers being paid a market price when demand is sufficiently high to merit their operation whereas renewable energy (in grossly simplified terms) has to date received a fixed or partially fixed payment whenever it is available to produce (e.g. when the wind blows). A marginal producer may also be able to earn revenues by supplying services to the grid such as balancing the intermittent nature of the renewable energy generation.

If demand is high and there is no renewable energy available (which carries a very low marginal cost) then the marginal price (the point at which demand is met) will be more expensive. If there was not a steady, contracted, base capacity provision then this could produce dramatic swings in pricing. The conclusion to be drawn in the context of the SEM is that, capacity payments and those who receive them are the backbone of a steady and well-functioning market and will continue to do so even as we further transition towards renewable sources.

The security of supply point will be addressed later, but it isn’t illogical to see that security of supply for Northern Ireland can be furthered by participation in the SEM, particularly within a continually changing energy environment.

How does renewable energy fit in to all of this?

The renewable energy landscape has developed rapidly over recent years and looks set to continue to do so with perhaps the most important factors being the increasing efficiency of (most) technologies combined with lower costs. What this leads to is what is known as “grid parity” or when the cost required to pay a renewable energy producer is the same as what electricity is bought and sold for at a wholesale price on the grid (i.e. without any payment on top of the market price). This is in a backdrop of European Union targets on decarbonisation and the Paris agreement on climate change, both of which require countries to emit lower volumes of harmful emissions.

Lower prices and potential grid parity notwithstanding, the nature of renewable energy means that a type of top-up payment or balancing payment is still often employed. This may not always be the case in future in Ireland (as is already the case in some other European markets) although it is set to be the case for the near to medium term (the Republic of Ireland has recently published its high-level design for its new support system, which does this whilst leaving space for further price improvements).

A fundamental reason for that requirement is that where a technology such as wind power (which is the largest renewable energy generation source in Ireland) is concerned, one cannot decide when it will and won’t blow and because wholesale market electricity prices will vary during the day, being exposed to that is not ideal from a development or financing standpoint Electricity is not a typical commodity therefore as it cannot be stockpiled and traded when we choose.

That’s a slight aside to how renewable energy fits in to the wider story of the SEM. However it is important because of what we touched upon earlier and the point around renewable energy only being available intermittently brings us back to the need to a) have sufficient capacity on hand always to meet demand; and b) using the market to then fill in the gaps on top of this.

Broadly speaking within the SEM if any renewable energy is available then it will be used as comes with limited marginal cost. Capacity contracted plant will then make up the difference (providing everyone with the comfort of knowing they are there and contracted to be available) with other marginal producers (i.e. those with no contractual responsibility but a desire to take part in the market opportunistically) coming in after that.

Battery technology is expected to change some of this (i.e. if we can store wind energy generated in excess through the night until it is needed during the day), but the architecture of the SEM should allow for that (although it will also need to evolve and take in to account the respective governments’ renewable energy policies). The multifaceted nature of integrating renewable energy in to the grid is very much part of the SEM’s remit and if society is broadly accepting that cleaner energy sources and electricity generation is what we want to do (both United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland government policies suggest that is the case, despite some noise from other factions).

What about solar panels on a rooftop – is that the same thing?

Although the main participants in the SEM are typically utility scale (i.e. large) that doesn’t mean an increased quantity of localised, smaller-scale generation won’t affect the grid. A current (and growing) consideration for the operation of the grid is how to deal with such generation being fed back in to the grid (where permitted) as this provides further uncertainty to be balanced, adding to the complexity of operations.

Something that will become a bigger issue in the future will the growth of off-grid and localised generation to the point of grid throughput being reduced so much that payments to the operator are not sufficient to cover required maintenance and capital expenditure (if this isn’t regulated properly – it currently is – then those payments would become prohibitively expensive meaning anyone relying on grid electricity would pay more for this to cover it).

Overall the renewable energy landscape is one that is going to continue to pose many difficult questions for system operators and there are new and different models emerging. In Germany some towns have taken back control of their own distribution grids by way of example – an equivalent would be Armagh running its own grid and buying enough electricity at a municipal level from PowerNI to provide for everyone. Having the ability to balance and source renewable energy from across Ireland instead of in smaller regions does have many positives however, provided the correct investments in infrastructure have been made to allow for these to be realised.

Is the SEM good for consumers?

In general, yes. The all-island market is often cited as an example of successful cross-border cooperation and that appears to have developed well over time. The SEM, whilst not perfect and in need of further largescale infrastructure investment, is seen as an efficient system. Having a larger marketplace opens greater competition which in turn should help keep wholesale energy prices lower than they might otherwise be.

As energy systems transition across the world to be greener and led by renewable technologies, having greater scale (and connectivity) will be important and Ireland is no exception. Smaller localised grids and greater ability to store energy in batteries will change the landscape, but a full-scale move away from our current systems is not going to happen tomorrow and having a system operating on an all-island scale provides greater scope for efficiencies in that regard.

The SEM also helps with energy security and greater development of the all-Island grid will further this. Connectivity to the British grid and energy market is important for Ireland however it isn’t a large enough connection to supply all energy needs and in any event the British system has its own energy security issues to worry about such as the ongoing supply of sufficient gas.

For the island of Ireland the north-south frameworks and cooperation that have helped build the SEM, alongside strong connections to the British grid would appear to provide a stronger platform for security. Essentially this is a system that is built with the needs of people and businesses on the island in mind, whilst remaining more widely connected (and therefore flexible).

And will Brexit have an impact?

If all that the British government and its European Union negotiating partners have said to date is to be believed then there should be no impact. Whether this turns out to be the case, only time will tell.

As mentioned at the start of this piece, the SEM has recently undergone a reworking for what has been termed the I-SEM (Integrated Single Electricity Market). The core objective of this is to align the SEM’s market mechanics to its European peers to enable (in theory) a single electricity market (or at least energy trading market) across Europe. Without going in to too much detail about what this means, a core objective is to enable producers in different countries to sell electricity to buyers across borders. The benefits for the public would be a larger market and therefore (in theory) more price competition (so theoretically at least the capacity auction in 2017 which helped reduce costs could become more competitive in future).

There are several technical challenges and differing viewpoints on this integration which I will not enter in to here but it is worth highlighting as it goes to point out how complex and challenging electricity markets are and will continue to be which reaches back to an overarching point that the pooled all-island expertise and experience is a stronger resource in this environment that fragmentation. To make this happen there must be no trading barriers (for electricity at least) between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland post-Brexit.

Seeing the bigger picture

One might reasonably conclude that an electricity market is more complicated than previously thought after reading this. And that would be fair – we have only scratched the surface of a few of its facets and I am no engineer to begin to explain the countless technical aspects that make this system work and function.

These are large collections of infrastructure that were designed with an operating model in mind and are now needing to adapt. More investment will be required, including to respond to market changes and policy direction.

There can be a lot of noise around electricity markets, particularly concerning end costs to consumers and jobs connected to the industry. These are important points however they cannot be addressed on a reactionary basis but need to be part of a longer-term strategy and plan that is implemented with such goals in mind.

The SEM is a cleverly designed system but it is operating in an uncertain and challenging environment. Well intentioned political support and interest to facilitate its development and further evolution will be increasingly important and the public should hold politicians accountable to do so. An electricity market is not an isolated bubble but an integral part of our everyday lives and it needs to serve today’s society’s needs first whilst being coaxed and coerced in to developing to trying to anticipate and to serve those ever-changing needs in the future.

It’s important for everyone living on the island of Ireland that the SEM functions well and efficiently and that politicians are held to account to ensure that it is performing correctly and delivering against the needs of society. Whether these are ensuring fair and equal access to well-priced electricity (which has clear social implications) or having a cost effective and certain supply for businesses either currently in Ireland or thinking about investment, the debate is one we should be having now.

This article was updated on 17 August.