In Northern Ireland there’s been a lot of speculation over recent months, dreams shared – maybe too loudly – of embarking on grand infrastructure projects, namely to connect ourselves physically with Scotland. Is a ‘Boris bridge’ possible? Would an underground tunnel be more practical? Given the reality of Northern Ireland’s state of connectivity, however – across the region, with the UK and Ireland, and the outside world – perhaps extravagance should wait. Just this week, more immediate transport matters were brought into sharp focus with the collapse of regional airline Flybe.

Of course no one a few months ago could have predicted the outbreak of the Coronavirus and its impacts on the global economy, not least the airline industry. But could Northern Ireland’s airports have been better prepared for Flybe’s demise? Are we over-reliant on old ideas to solve problems? On the ground, it’s clear that long-term lack of infrastructural ambition continues to put businesses and communities at a disadvantage. In future, making Northern Ireland better connected on a regional, national and global level, and in a way that’s sustainable, will be crucial in determining NI’s success, attracting financial investment and promoting here as a great place to live and work. Let’s explore the problems and potential solutions.

Trouble in the air

Is cutting Air Passenger Duty (still) the only answer?

Being on an island, having efficient air connectivity is a huge issue for Northern Ireland – a point very clearly illustrated by the collapse of Flybe, an airline which until recently accounted for three-quarters of movements at George Best Belfast City Airport.

One of the key struggles for Flybe, and other regional airlines, has been Air Passenger Duty (APD). Did you know that a return flight from Belfast to Manchester comes up with a tax bill of £26? It’s certainly a money-spinner for the government, bringing in around £3.7 billion each year.

The debate around APD in Northern Ireland is certainly not a new one. Nearly ten years ago, the tax made headlines in 2011 when the UK government devolved APD-setting powers to NI for long haul flights from Belfast International. As a result, the NI Executive slashed APD on routes between Belfast International and Newark, New York to help ensure that Continental Airlines stayed on the transatlantic route. At the time, the UK Treasury also stated that it would launch “a parallel process to devolve aspects of APD to the Northern Ireland Assembly, as a recognition of its unique circumstances.” Yet no such form of devolution has ever occurred in full. Perhaps if APD had been further devolved, and consequently cut for domestic flights, Flybe may still have been alive today.

More recently, when the DUP’s confidence-and-supply deal with the Conservative Party was agreed in 2017, APD was clearly noted as a matter to be discussed post-Brexit. After Boris Johnson’s victory in December’s general election, it’s fair to say that the DUP’s influence in Westminster is not what it once was, and the issue seemed to have disappeared entirely until the airline industry called on the Treasury to suspend APD altogether for six months. So far these calls have been to no avail, with no concrete commitments in Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s first Budget.

Similarly, in the recent New Decade, New Approach deal that returned power-sharing at Stormont there was no mention of APD, but a commitment to “achieve greater connectivity on this island – by road, rail or air.” The only substantive aviation issue mentioned within the deal concerned all-Ireland routes – a pledge to look into the possibility of routes between Cork and Belfast, and between Dublin and Derry. Whilst it’d certainly be handy to nip on a plane from one side of the island to another, this is hardly addressing the bigger issues Northern Ireland faces with regard to air connectivity and attracting more airlines to do business.

An airport crisis waiting to happen?

Despite being Europe’s largest regional airline, it’s no secret that Flybe’s financial condition had been unstable for some time, so the now immediate threat to the long-term viability of Belfast City Airport really shouldn’t come as a surprise to policy-makers. The airport itself has showed ambition for growth with plans to extend its runway which they argued would attract new airlines and routes. However, in 2012 the proposal was withdrawn following a lengthy planning application process which began in 2008. Today, it’s not just Flybe’s departure that will leave the airport weaker – only last September Aer Lingus announced it was cutting out its summer holiday flights from the airport.

Looking to the North West, City of Derry Airport is hardly secure either, with only a handful of routes. Its newly appointed manager faces a big challenge. Only in November the airport told local councillors that a £6 million cash injection would be needed to continue operations beyond 2021.

Belfast International Airport has its woes too. Whilst there hasn’t been so many media reports of travellers queuing endlessly for security in recent months, flight routes have been cut, including some by Ryanair and others as a result of last year’s Thomas Cook collapse. The airport now lacks any transatlantic flight other than the seasonal service to Orlando.

This uncertain picture of Northern Ireland’s airports is framed against a backdrop of a highly successful Dublin Airport. The super hub boasts good ground connections and a huge range of destinations, including budget flights with the likes of Ryanair. It also has US pre-clearance, saving travellers time on arrival, unlike any potential transatlantic routes from Belfast.

Given how numerous NI’s aviation problems are, you might have expected connectivity to have been a more significant priority for Northern Ireland’s political parties on their return to the Executive in January. There seems to be a real lack of ambition in this regard, perhaps reflecting a tacit admission that Dublin Airport is now the main hub for air connectivity on the island.

How to match our rail potential?

If there is a lack of strategy for effectively connecting Northern Ireland to the wider world, even more worrying is our lack of ambition to develop sustainable infrastructure within Northern Ireland. Just look at this map, posted by Professor Paddy Gray on Twitter. Compare the railway infrastructure in the North compared to that of the South of Ireland. Right across NI there are stark blind spots – like a severe lack of railway infrastructure west of the River Bann, with only a handful of stations.

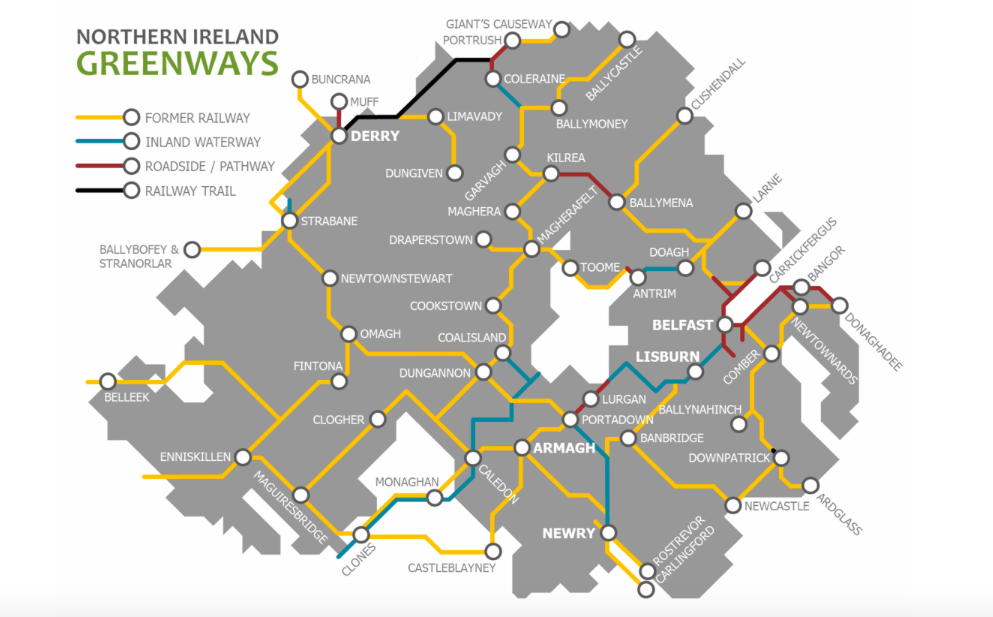

But if we look at another map – a map of Northern Ireland Greenways (below) – the potential for expanding our rail infrastructure is huge. Around 1,000km of former transport routes lie completely abandoned, ripe for development. This is not to suggest that 1,000km of new railways should be laid to ruin the countryside. Instead, surely work should be done to assess the need for new infrastructure, plotting out exactly which lines and stations are in most need, weighing up the environmental benefits against any costs.

Northern Ireland’s existing railway provision is in need of bolstering too. Just look at our cross-border connections – at the moment, there are only eight return services each week day between Belfast and Dublin. Plans are out there as to how the service could be improved but there seems little political will to make this vision a reality.

Journey times are not exactly short either. A glance of Translink’s website demonstrates that a train from Great Victoria Street to Derry takes 2 hours 12 minutes. In comparison, the 212 bus can take just 1 hour 45 minutes. Somewhat similarly, a train from Belfast to Dublin takes 2 hours 5 minutes – a direct bus, only 1 hour 50 minutes.

With the debate around Northern Ireland’s air connectivity now firmly on the agenda, it’s important not to lose sight of the patchy infrastructure on the ground. In a positive development this week, actually, this call to improve local railways has been made by Minister for Infrastructure, Nichola Mallon MLA. Her and her Scottish counterpart, Michael Matheson MSP, have written to the UK Transport Secretary, Grant Shapps MP, calling for any increased devolved transport budgets to be set aside for more local projects rather than the extravagant ones alluded to in this article, most notably the ‘Boris Bridge’.

The two ministers, who it’s worth noting are both of a nationalist persuasion, have called for increased discussion with the devolved administrations when it comes to looking at local infrastructure priorities. This is the sort of approach that would serve Northern Ireland, and Scotland well. Detailed policy making spear-headed from the countries themselves rather than being centred and authored around a London and England-centric UK economy. This approach of listening to the devolved administrations can also serve unionism well. It can show that the UK Government cares about the likes of Northern Ireland, actively seeking their views on policy going forward.

Can NI become more connected, less Belfast-centric, and more sustainable?

Improved transport infrastructure, no matter the mode, boosts at least the potential for better economic performance. Improved transport to and around Belfast would be welcome, of course, but surely more focus must be set on many other areas where Northern Ireland suffers a clear imbalance. More must be done to make NI less Belfast-centric, to grow our economy more evenly and spread benefits to more rural towns and villages.

The economic case for increased investment is clear. But transport can also help greatly with social mobility, ensuring that the vulnerable and elderly do not become isolated. On paper, any investment should be worth the money – in Northern Ireland social transformation must also be taken into account.

Whatever the form of transport, politicians need to consider a longer-term strategy for how NI offers itself as an attractive destination for investment, tourism, for living and working. With such a lengthy list of issues, and we’re told a limited money pot, it’s time the Executive became more creative. How about a two-pronged approach – politicians using their own political power for one, and other to use their influence to attract investment.

If the recent election in the Republic of Ireland is anything to go by, increasingly politicians here may have to look beyond their target audience who support or may be swayed by their stance on NI’s constitutional issue, to earn the votes of a new, environmentally-engaged generation of voters. Any infrastructure agenda will have to balance the demand for connectivity with the need to be more sustainable.