As Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson was being cared for in a London hospital this week, the reality of the impact of the Coronavirus on global politics took on a grim face. But with some 100,000 deaths across the world and a million and a half people infected, that reality had already taken hold in far too many families, for whom politics is easily the last thing on their minds.

Yet at a time when fearful citizens most need confidence in their governments and look to their leaders for reassurance and order, there is serious disruption to elections in Britain and all across Europe, with the return of an underlying feeling that the only certainty is uncertainty – the gloomy tagline for our times that we all hoped had been reserved exclusively for Brexit.

Amanda Sloat of the Brookings Institute wrote recently that: “Political parties and the electorate understand the rationale for postponing elections during the coronavirus pandemic, especially given the importance of social distancing to reduce the spread of the disease. All governments, including those whose mandates have been extended, are primarily focused on emergency management at this time.”

In such a troubled landscape, it’s difficult to see what might lie even seven days ahead, let alone several months. And this is particularly true in the US, where a strung-out election process can be close to chaotic even at the best of times.

The US Surgeon General had warned that this week in the battle against the virus would be grim: the equivalent of a “Pearl Harbor or 9/11 moment.” But with the numbers of fatalities continuing their relentless rise, the nation has easily surpassed many multiples of both those pivotal events in its history; and even with prediction models shifting daily the other side of the “peak,” as it ripples across the country, appears some way off yet.

Against that backdrop, the state of Wisconsin was thrust into turmoil when the US Supreme Court controversially ruled that its primary election had to go ahead on Tuesday, despite an attempt by the Governor, Tony Evers, to delay the contest until June on the grounds of public safety and extend absentee voting to prevent people having to turn out in person.

The subsequent chaos as many waited in long lines to vote – not just for the presidential primary but for a number of important local offices including a seat on the state supreme court – gave a worrying hint of what might be in store between now and November. Every other primary scheduled for April has been postponed until June or moved to by-mail voting only. Even by June, though, New York – one of the states involved – will likely still be struggling with bearing the brunt of the virus.

On the face of it, it seems fundamentally unfair to force anyone to choose between exercising their vote and protecting their health. Yet, even though a majority of Americans of both political parties favor using mail-in ballots while the Coronavirus threat continues, the president remains opposed, contending that it encourages fraud (which, while there are issues with the format, is a claim for which there seems little evidence) and even, on a call-in show with Fox News, admitting that making voting easier works against Republicans.

Voting Rules

The Trump campaign and the RNC are already aggressively trying to prevent any change to voting rules because of the outbreak. But the biggest headache is a lack of uniformity across the states over their election processes, with both parties understanding that the current emergency could have a huge bearing on who votes and how, and what that means for some key states.

According to Reuters: “The drama in Wisconsin foreshadows legal battles and political showdowns looming in upcoming primaries across the country, and heading into the all-important November presidential election, as the worst public health crisis in a century upends voting, Democratic officials, non-partisan voter advocates and election watchdogs say.

“They are particularly concerned about the potential impact in closely fought battlegrounds such as Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, whose contests were decided in Republican President Donald Trump’s favor by razor-thin margins in 2016.”

The virus has certainly upended the traditional political calendar and created a new, unprecedented landscape, with normal campaigning on hold – how strange might it be for a politician to never shake another hand – and doubts over the party conventions this summer. The Democrats, who originally planned to gather in Milwaukee in July, then decided to delay by a month, are now exploring the idea of some kind of “virtual convention” to avoid a large-scale public gathering.

Republicans, and the president, seem determined that their own convention, set for Charlotte in the third week of August, will go ahead, but a final decision on public health grounds might yet come down to local officials.

If Wisconsin did provide one measure of clarity amid the cluster, however, it proved to be the tipping point in the Democratic primary contest, with Sen Bernie Sanders accepting what became increasingly inevitable and ending his campaign. With Joe Biden now the presumptive nominee, his pledge to choose a female running mate takes on a heightened importance, as does the extent to which he might adapt his positions to appeal to Sanders’ supporters. You’d have to guess that making the pitch for universal healthcare and better protections for low-paid workers has become a little easier in recent weeks. As it often appears with the party as it approaches what should be a slam-dunk, though, the question is whether it can really unite.

Tom Friedman at the New York Times has an idea of what kind of unity is important right now – one that transcends hyperpartisanship. He writes: “Biden needs to show that he isn’t running to be president of the 48 percent (or less), as Trump is; he’s not trying to suppress the vote, as Trump is; he’s not running to squeak by in the Electoral College, as Trump is. He needs to show he’s running to be a majority president, a unity president — but not just unity for unity’s sake, but unity of purpose based on a set of shared values for rebuilding America.”

Partisan pandemic

Like it or not, though, while the virus respects no red or blue boundary, the response to it, inevitably, is intensely political. If it was not already, the current emergency is becoming a partisan pandemic, with splits along party lines across the country at the worst possible time for the collective public health.

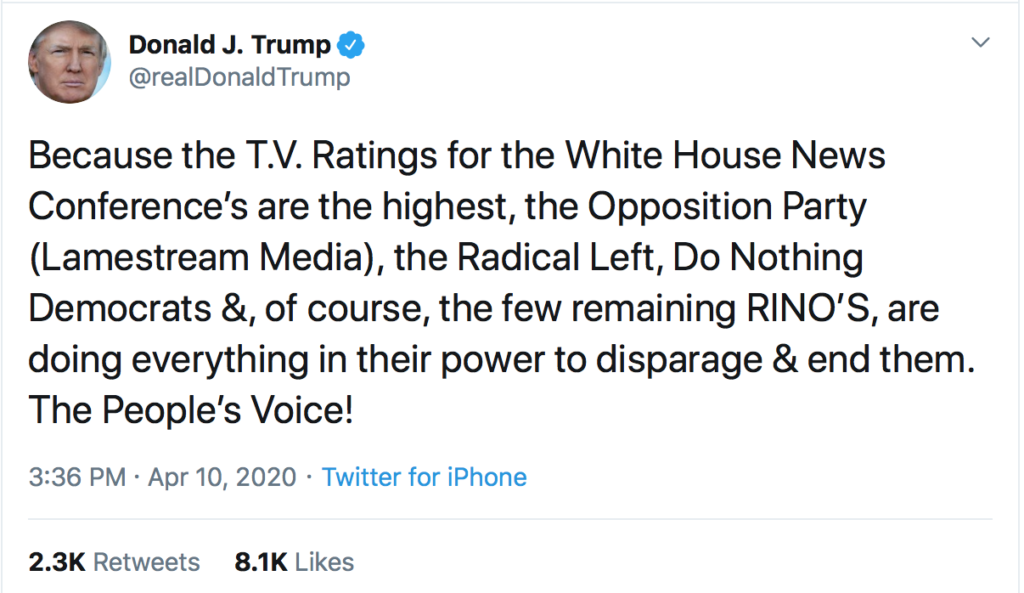

At one of his recent “five o’clock follies”, the nightly press briefings that have taken the place of campaign rallies – and what Jon Meacham has called “weaponized narcissism” – President Trump, under increasing pressure over the difference between his administration’s words and actions – was asked directly about the sanctity of the November 3rd election.

He said he was committed to the election going ahead (he doesn’t have the power to delay it, regardless of what any social media posts might suggest) despite warnings that there may be a resurgence of the Coronavirus in the late summer or fall, particularly if the country was to abandon its social distancing policies and “reopen” too early.

Ironically, with the nation on lockdown, people have more time to watch television, and they’re watching the president’s daily performances become increasingly detached from their own realities as they face grief, unemployment and uncertainty. As they watch, all but his most devout supporters can’t avoid but see him flailing in his emergency response as he prioritizes his re-election and ratings at the expense of daily death tolls.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the president’s approval rating has been slipping from its level early on in the emergency, leading even some of his allies to suggest that he needs to rein in the daily circuses. Prominent conservative Bill Kristol, though, thinks it might be too late for that, fearing that Trump has broken the GOP for good.

“We have now reached the terminus of craven loyalty and pathetic apologetics,” Kristol writes. “I don’t see how either the political institution of the Republican party or the intellectual movement of conservatism recovers from what we have seen over the last three years – but especially the last three months.”

Hurting the party, and the base?

Perhaps the greatest irony, of course, as Fintan O’Toole points out in his latest piece at the New York Review of Books, is that the people who might bear the biggest brunt of the virus and Trump’s initial reluctance to take it seriously, will be his own supporters. O’Toole writes:

“His followers got the message that the whole thing might well be a media and Democratic conspiracy, and therefore that they did not need to take the threat seriously. A Quinnipiac poll on March 9 showed the effect: while 68 percent of Democrats said they were concerned that they or someone they knew would be infected, only 35 percent of Republicans felt likewise. Belief in the seriousness of the threat is a prerequisite for self-protection (not to mention for reducing the spread of the virus) — Trump’s undermining of that belief is literally lethal to his own supporters.

“For we must bear in mind that Trump’s “real people,” the ones who make up his electoral base, are disproportionately prone to the chronic illnesses (the “underlying conditions”) that make Covid-19 more likely to prove fatal. A 2018 Massachusetts General Hospital study of more than three thousand counties in the US reported that: ‘Poor public health was significantly associated with the additional Republican presidential votes cast in 2016 over those from 2012. A substantial association was seen between poor health and a switch in political parties in the last [presidential] election.’”

For now, a new CNN poll gives Biden an edge, but there’s a worrying sign over his supporters’ enthusiasm. Whatever way the virus progresses over coming weeks and months, though, it might all still come down to what shape the US economy might be in by election day. And while Wall Street has rallied this week, predicting this far out how the economy might be performing – and how the financial circumstances of the staggering numbers of newly unemployed might look – is certainly a fool’s errand. It’s probably no wonder that one of Trump’s recent tweets suggested that the effects of the virus should be “quickly forgotten” as the country seeks to move on. So much for the comparisons with Pearl Harbor or 9/11.

It’s looking increasingly possible, as Matt Flegenheimer writes in the New York Times, that the most important election of our lifetimes will turn out not to be the next one, but the last one.

“This is the grim diagnosis now among some opponents of President Trump, who see any hopeful predictions of the past – that the job might change him, that one term is not so long, that perhaps presidents do not matter all that much anyway – collapsing beneath the weight of a crisis whose costs are too bleak to bear.

“Mr. Trump is in charge during a generational emergency, briefing the nation on life and death with an eye toward television ratings and miracle cures. It can feel unlikely that any choice in 2020 will be as consequential as the fact that he won in the first place.”

* The remarkable photo at the top of this piece was taken by Patricia McKnight, an intern for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. As it circulated around the world, it summed up a strange day and was described as an “era-defining image” and a “perfect picture of our times.” It is a story in itself.

See Also:

Faith and Moral Bankruptcy – Mar 26

In Shadow of Virus, Biden puts Distance Between Himself and Sanders – Mar 18

Last Man Standing – Mar 10

South Carolina – Comeback Kid Set for Super Tuesday Showdown – Mar 2

New Hampshire – Not Even The End of the Beginning – Feb 13

Democrats Look to Put Iowa Behind Them – Feb 8

And read Julia Flanagan on the Democratic debates here:

Democrats face Foreign Policy Test – December

The Road To Iowa Goes Through Georgia – November

A Dozen Deliberative Dems Debate – October

And Then There Were Ten… For Now – September