“At all stages we have been guided by the science” (Boris Johnson), “we need to listen to what the science says” (Arlene Foster), “It’s a war” (Italian medic), “Horse Racing Ireland: putting people before profit” (RTE News, 15th March 2020), and this remarkable statement from Irish Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar,

“I know that I am asking people to make enormous sacrifices. We’re doing it for each other. Together, we can slow [it] in its tracks and push it back. Acting together, as one nation, we can save many lives. Our economy will suffer. It will bounce back.”

The ‘it’ here and the background reason for the other statements is not addressing the climate and ecological emergency, but the coronavirus crisis of course. Yet unlike the coronavirus, there have been official political declarations of ‘climate and ecological emergencies’ from parliaments in the EU, UK, Ireland, France and over half of UK councils. But, unlike the determined and swift actions of most governments around the world – from China, to Italy, Ireland, the USA – to the public health threat from Covid-19, there is little evidence of the same governmental determination to take radical and tough decisions on the climate and ecological crisis. It is pertinent to ask why not, given the latter crisis presents an even greater threat to the lives of vulnerable citizens in those ‘minority world’ countries and others in the global south or the ‘majority world’.

Could it be that all these declarations of ‘emergencies’ are just that? Some ‘in tune’ public and ‘politically correct’ rhetoric and associated positive media coverage for politicians forced by mobilisations like Extinction Rebellion and the Youth Strike for Climate to do (or say they will do) more on climate action? Cheap talk about recognising there is an emergency…. But in reality not believing it really is an emergency? Why is it that our political leaders listen to and make decisions informed by the science in the case of coronavirus – closing schools, restricting travel, putting in place financial support for those who ‘self-isolate’ etc. – but not when it comes to the climate and ecological emergency?

Two crises, different responses

Here we need to start from asking a simple but revealing question: Why do we see politicians acting on medical science and expert advice on how to deal with the coronavirus, including making some very difficult decisions, but not on the climate and ecological crisis? While politicians say they accept the climate science, we have very little evidence of the type of action consistent with what the climate science recommends. The climate science indicates we need to urgently and at scale decarbonise not just our energy system (i.e. move away from a dependence on coal, oil and gas) but decarbonise our economies and ways of life: how we travel; the resource inputs and structure of our food system; how we build and maintain our urban spaces and homes; to our views of the ‘good life’ and expectations of ‘normal’.

Responses to the pandemic have led to dramatic and radical changes to the lifestyles of most people in countries most affected. These range from citizens staying at home (whether ‘self-isolating’ and/or working from home, with some people forced to do so as in Italy and France), a massive drop off in air travel, car journeys, and community self-help with neighbours and organisations helping the most vulnerable (but this needs to be balanced with some ‘panic buying’ of food, household items and medicines in some countries such as the UK).

And when we look at some state responses we can also observe radical action. Perhaps the most dramatic of which is the Spanish government taking all of Spain’s private health providers and their facilities into public control as it declared a national emergency. Along with Italy, Spanish regulators also implemented a ban on the short selling of stocks in more than 100 companies. Other radical initiatives include the temporary suspension of evictions, mortgage holidays and the UK government committing to pay 80% of the salaries of employees who no longer have any work to do. Even in that most neoliberal of states, the USA, we see federal transfers of cash to hard pressed Americans.

However, while there is a flurry of discussion and proposals to link the response to the pandemic to addressing the planetary crisis (and this ‘Gas’ is a contribution to that growing body of ideas), there are questions to be considered as to whether we can or should link them, and even if it were possible, can the same ‘crisis/emergency’ response we see in the pandemic be replicated in responding to the planetary crisis? The reality might be that unlike Covid-19, climate breakdown and ecological devastation, is not impacting the lives of people in the minority world, it is not something these populations can see rapidly spreading and killing people around them within their own communities and societies.

Climate breakdown is more abstract, distant in space and time, than the pandemic which is a ‘clear and present danger’. The dominant public and political discourse around the pandemic is that it will be defeated and therefore a ‘temporary risk’, the drastic changes to our lives are short-term, and then there will be a ‘return to normality’. In short, there is confidence (warranted perhaps) of ‘solving’ the Covid-19 crisis.

This is not the same with the planetary emergency which, even if we were to achieve the impressive task of getting greenhouse gas emissions down to stay within a two degree warmer world, would also mean us having to adapt to a climate changed world. There is no ‘solution’ to the climate crisis, only adaptive and on-going coping strategies, over a much longer period of time. The demand for ‘emergency solutions’ could usher in large scale technological solutions such as geo-engineering; proponents regularly view such planetary scale technologies as ‘insurance policies’, but they bring with them a ‘moral hazard’ of distracting or downplaying mitigation efforts.

The fears and concerns around the virus within populations in the minority world which legitimate (at least for now) the unprecedented changes in our lives, including the restriction of our mobility, and the rapid intervention of the state into the economy cannot be said to be present within the same populations around the climate and ecological emergency[1]. However, this is not to say that this is case for other populations more directly experiencing the ‘real and present dangers’ of climate and ecological breakdown in the global south.

While this has arguably always been the case for those in the global south suffering the impacts of planetary devastation here and now, it is increasingly a ‘red line’ for those nations within international climate politics, as witnessed at the last climate summit in Madrid in December 2019 which ended in failure due in large part to the unwillingness of the high carbon emitting global north to accept responsibility and obligations around the ‘loss and damage’ from climate breakdown caused by minority world emissions, in nations in the global south.

A final set of caveats to be considered are the dangers from mobilising action or framing an issue in terms of ‘crisis’ or ‘emergency’ which can suppress discussion and debate. Here we can witness how the UK government has suspended debates in Parliament and thus the scrutinising of the government’s response; how a reactionary ‘Brexit-Covid nationalism’ is being promoted by some elites; or the brutal way the Chinese government approached the pandemic in Wuhan. Or the ever-present dangers of a new round of entrenching neoliberalism through a pandemic mode of ‘disaster capitalism’ as ‘Coronavirus capitalism’ as Naomi Klein calls it, or the ‘crowding out’ of calls for more localised, distributed and variegated responses.

Despite these concerns that there is no direct ‘read across’ from the pandemic to the planetary emergency, there are surely lessons and insights and glimpses from responses to the pandemic as to what might work to speed and scale up climate action. Some of the changes to the daily lives of citizens we have witnessed, and actions by some states, could be viewed as ‘dry runs’ for the types of changes the 2018 IPCC report recommended when it stated that “limiting global warming to 1.5C would require rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” (IPCC, 2018).

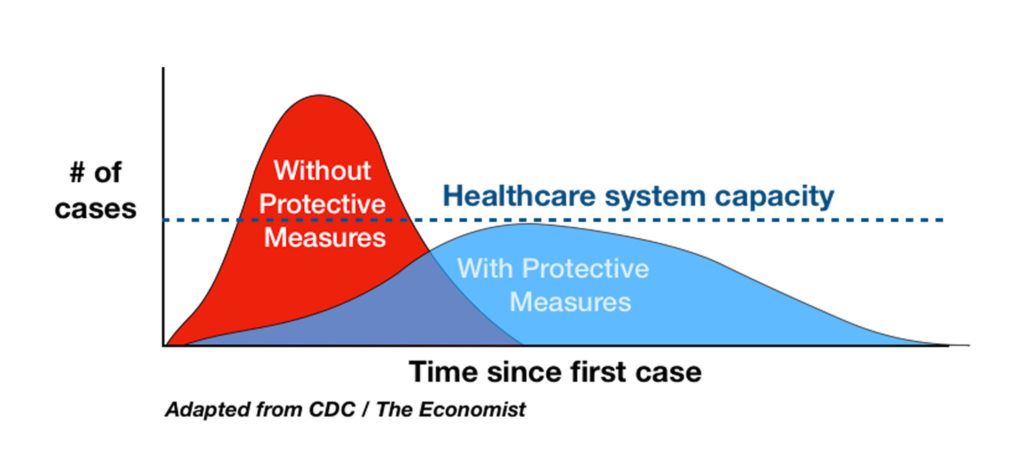

They can also be seen as suspensions of ‘business as usual’, temporary and extraordinary measures deemed as necessary state actions (and largely so far accepted as necessary by populations) to meet and overcome the pandemic. The latter has been framed in many countries as ‘flattening the curve’ – delaying, via some of the drastic actions above, the sharp peaking of the inflection rate and thereby spreading out over time the numbers of people infected to enable health care systems to cope.

From ‘flattening the curve’ to ‘bending the curve’?

It is welcome and heartening to see how quickly the graph in Figure 1 and the rationale behind the importance of ‘flattening the curve’ has gone viral (excuse the pun) as one of the dominant communicative framings of what the public can do to halt the spread of the virus. This ‘flattening the curve’ idea is simple, clear and intuitive, and gives people a sense of agency. It also enables people to understand the rationale for and aims of government action, and reasons for the necessity of altered social practices and changes in lifestyles.

Can something similar be used to promote and communicate to people the same logic in relation to our planetary emergency? Can the simple effective and mobilising pandemic communication of ‘flattening the curve’ (above) but applied to a climate crisis one of ‘bending the curve down’ (below)?

An important point here is that while medical innovation is needed to cope with the virus: testing kits, new ventilators and ultimately a vaccine, and a massive ramping up in production of required equipment – including ventilators, face masks, gloves, etc., to address both crises social innovation and new social practices are vital.

This not only gives people a sense of agency, that through social distancing, self-isolating, reducing red meat consumption or international flying, they can ‘flatten the curves’. It also demonstrates that there are cheap, non-technological political and behavioural changes – what might be called ‘social innovations’ – that can be also be effective. That is, in relation to climate breakdown, we can choose expensive (and non-proven) ‘big tech’ or we can choose new ways of living and new material and social practices.

Essentially the choice here comes down to ‘greening business as usual’ via technological adaptation to our climate-damaged and carbon constrained world, or disrupting business as usual and fundamentally restructuring our systems of energy, food, transportation etc. to create a different and less unsustainable political economy. What if the latter is the most effective way to ‘bend the curve’ on climate and ecological breakdown?

This is especially the case when we consider how it is it not the virus itself that will kill and harm people, but our capacity as society’s to respond to it, not least in terms of helping the most vulnerable. While the virus is natural, it is our social response to it that is and will determine how badly affected our societies will be. On this issue two related ideas come to mind, both in relation to famine.

Firstly, a well-known (but contested) summary of the great Irish famine of the 1840s, one version of which goes, “The Almighty Sent the Blight, but the English Created the Famine.” This could be updated to read, “Bad luck created coronavirus, but capitalism caused the pandemic,” as we see significant differences within European public health care systems in terms of being prepared for the pandemic, with some, like the UK suffering from a decade of being starved of resources and investment by policies of austerity.

Secondly, there is Amartya Sen’s argument that famine is not the absence of food but the absence of the ability to buy food, and that we need to look at politically structured and supported entitlements to food not merely food supply. It is for this reason we do not see famines in welfare states where people have welfare rights and hence an entitlement to food (imperfect though this is). As in the Covid-19 pandemic, the necessity for and the positive role of the state cannot be underestimated.

At the very least, ‘Bending the climate curve down’ could be a simple message to communicate the collective action necessary to both adapt to and also reduce the root causes of our climate crisis. Just as ‘social distancing’ and ‘flattening the curve’ are examples of community design principles for managing our common health and healthcare resources, so ‘bending the curve down’ could function as a design principle for responding to our planetary emergency.

This is an abridged version of a longer report: ‘This what a real emergency looks like: what the response to Coronavirus can teach us about how we can and need to respond to the planetary emergency’, available here.

[1] I owe this point to John Foster.