As we approach the end of the decade, it’s an opportunity to pause and consider on our place in time and space. Some thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Laney Lenox reflects on the the similar yet different divisions that continue to exist in Belfast – and what both cities can aspire to in the decades to come.

This November, Berlin erupted in a furious array of memorial events and celebrations to mark thirty years since the opening of the Berlin Wall. The Mauerfall Festival coincided with my first week conducting ethnographic fieldwork in Berlin as part of my doctorate at Ulster University.

As an anthropologist studying mechanisms for dealing with the past in societies affected by recent conflict and division, much of my time is spent in sparsely populated museums and memorials taking copious notes and, at times, navigating significant language barriers. So, I attended as many talks, art installations, and museum exhibits as possible during the festival.

Commemorating the past

QR codes placed at significant sites around the city for users to engage with stories and historic info over Facebook messenger.jpg

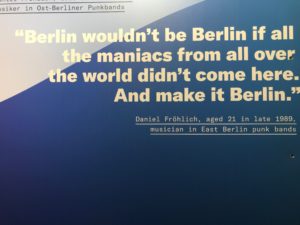

Overwhelmed by the Maurfall Festival’s breadth and accessibility, I found myself having to queue up half an hour early for talks on the immigrant experience in the former German Democratic Republic, or GDR (the former East German state during the Cold War), and other reflexive discussions on the events leading up to and later following the dismantling of the wall.

The panels were translated into English live through a set of headphones. There were virtual reality exhibits bringing a visual component to oral history projects, QR codes that when scanned would send messages to your phone, an augmented reality app that provided stories based on your location in relation to where the where the wall used to stand.

Despite this accessibility and opportunities for direct engagement with the memorial process, during much of the festival I felt overwhelmed and confused. During what often felt like chaotic wandering – which I had to believe was calculated and significant ethnographic observation – I noticed an exhibit near the Brandenburg Gate featuring walls around the world.

As eager as I’d been during the last few months to leave Belfast for my Berlin adventure, I found myself hoping Belfast’s peace lines would feature in the video installation.

Northern Ireland as a ‘blueprint for peace’?

I was not disappointed; the exhibit, which consisted of video interviews conducted with residents that lived on either side of four different walls around the world, brought me a sense of familiarity. It grounded me in something I knew. However, after watching the Belfast portion of the exhibit in its entirety, I began to wonder how appropriate the juxtaposition was.

The Berlin Wall stood between two states. While both walls could be said in some ways to divide communities and ideologies, the Berlin Wall stood much as a direct representation of top-down citizenship restriction. Many died in their attempts to cross the Berlin Wall or in direct relation to the division it caused – its official memorial site counts 140 deaths between 1961 and 1989.

The comparison is made in Belfast as well. The first time I saw the Falls/Shankill peace line, the tour guide pointed out that it stands twice as high as the Berlin Wall once did. Whether or not this was the intention, the implication to me at the time was this: a wall twice as high meant a division twice as deep.

At the time I was a 20-year-old undergraduate student on a study abroad semester. My worldview was full of certainty. As a student of peace studies, I saw my task as learning a ‘blueprint for peace’ that could be exported around the world. Because the Northern Irish peace process is widely spoken of as one of the most successful in the world, my time in Belfast was meant to be a significant part of learning and disseminating this blueprint.

Each year of my research and study loosens my grip on any preconceived notions about certainty a little more. Many on either side of the Falls/Shankill peace line (or on either side of any of the peace lines in Belfast, for that matter) speak of the wall as a comfort—a needed division while the conflict is still so recent and wounds still so fresh. While this does not in any way suggest this is how everyone in Belfast feels about these walls, the point about community versus state division and community opinion regarding the walls is significant.

So, how appropriate is it to continually speak about all walls as created equal? Or, is this not what the juxtaposition does at all? Rather, in considering the walls in relation to one another, do we gain a better understanding of both? In our consistent effort to understand things in the context of what we already know, does this juxtaposing of walls make sense and help us see what we already ‘know’ from a different perspective?

Discounting and justifying the Belfast/Berlin juxtaposition

‘You say nothing on the phone’ installation at the Stasi Museum, housed in the former Stasi Headquarters

Belfast (more specifically Seamus Heaney) came to my mind at a different exhibit at the Mauerfall entitled ‘You say nothing on the phone’. This installation consists of different landline telephones. When picked up, these phones play phone calls the Stasi recorded as part of their extensive surveillance state.

Even in doing so, I knew the connection my mind immediately made to Heaney’s ‘Whatever you say, say nothing’ was not entirely appropriate. ‘You say nothing on the phone’ referred to an intensely deep state surveillance system, whereas Heaney is discussing how communities talk (or avoid talking) to one another. Of course, the GDR relied on neighbours, friends, and even spouses and families informing on one another. So, perhaps in that way some similar themes of intimate distrust emerge.

My mind ran in circles to in equal parts try to discount and justify the juxtaposition it immediately wanted to make. Perhaps, just like the walls, we cannot help but place in side-by-side analysis, if not direct comparison, that with which we are familiar with that which we are trying to understand.

As we move into a new decade, it is my sincerest hope that in cities like Belfast and Berlin that have experienced divisions and distrust, however similar or different their contexts may be, the space is left open to analyse and understand the past publicly and to continue grappling with our own singular and collective uncertainties.