When the Trump administration this week moved to rescind the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, the measure which provided a platform for illegal immigrants brought to the US as children to remain under certain conditions, it was always going to be controversial.

Some speculated that the decision – like other campaign promises – was simply one more step towards undoing everything associated with his predecessor. Indeed, it led former President Obama to comment on his successor’s actions for just the third time since leaving office, saying: “There’s a difference between that normal functioning of politics and certain issues or certain moments where I think our core values may be at stake.”

Almost 800,000 DACA recipients have received approval to attend school and work legally in the US. As of Tuesday, no new applications will be accepted, while the wind-down of the programme – despite the President’s confusing follow-up tweet about possibly “revisiting” the scheme – could lead to thousands of deportations.

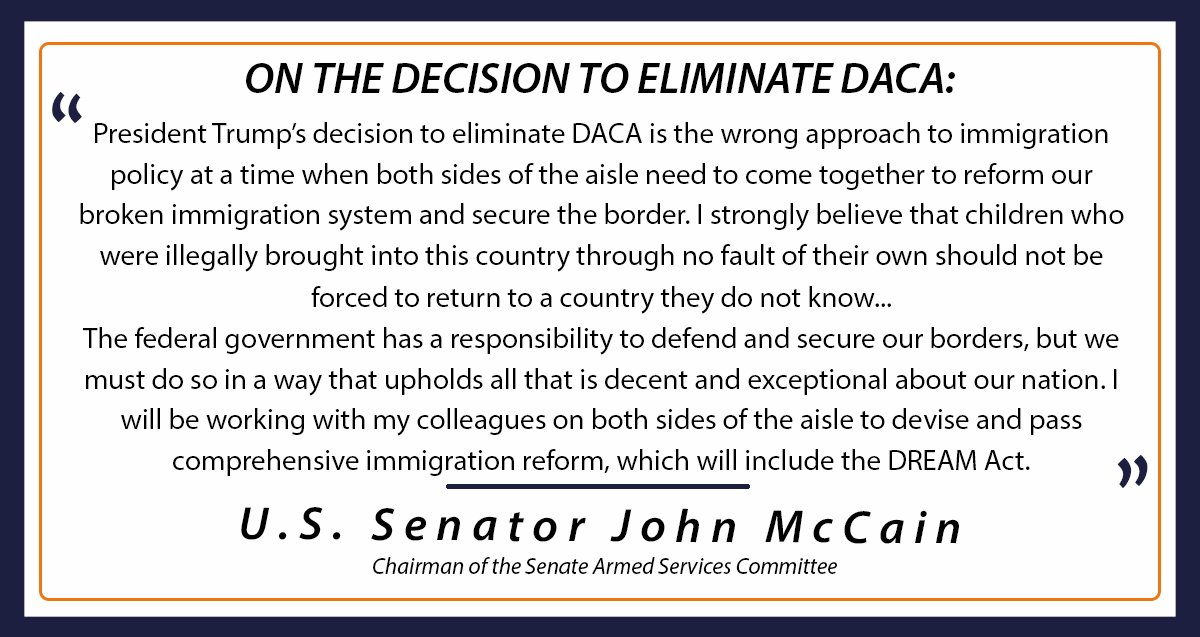

President Trump apparently wants to believe the six-month window until full implementation will force Congress to act, yet despite individual expressions of opposition, like that from Sen John McCain, Congress has consistently failed to formalize what Obama himself called a “stopgap” measure. It remains to be seen whether it will do so now.

In addition to shock and uncertainty among those directly affected – the so-called Dreamers – the administration’s move provoked a series of legal challenges as well as broad criticism from human rights organizations and faith groups.

And it also triggered a fresh wave of public protest across the country.

From outside the White House to outside Trump Tower in New York (where further demonstrations are planned for this coming weekend) to cities like Chicago, Miami, Los Angeles and San Francisco, there were angry signs of organized protest. In Denver, high school students at a number of local schools staged a walk-out.

Disasters, natural and man-made

The latest book by journalist and author – and former adviser to Al Gore – Naomi Klein looks in part at the nature of protest and the manifestation of opposition in the current political world, where what she calls the “shock politics” of Donald Trump and the forces that brought him to power have presented a fresh range of challenges, particularly, she argues, in another apposite debate right now, in the field of climate change.

The “not enough” part of her analyisis is a consideration of what she believes ordinary people can do about it.

From the Women’s Marches the day after President Trump’s inauguration to the DACA protests this week, the concept of a grassroots, if disjointed, “resistance” has run parallel to the Trump administration at every turn. Klein believes that the urgency of opposition transcends party politics. She writes:

It’s becoming possible to see a genuine path forward – new political formations that, from their inception will marry the fight for economic fairness with a deep analysis of how racism and misogyny are used as potent tools to enforce a system that further enriches the already obscenely wealthy on the backs of both people and the planet. Formations that could become home to the millions of people who are engaging in activism and organizing for the first time, knitting together a multiracial and intergenerational coalition bound by a common transformational project.

The plans that are taking shape for defeating Trumpism wherever we live go well beyond finding a progressive savior to run for office and then offering that person our blind support. Instead, communities and movements are uniting to lay out the core policies that politicians who want their support must endorse.

The peoples’ platforms are starting to lead – and the politicians will have to follow.

As Gillian Tett writes in her review for the FT, the “practical manifesto for opposition… starts by noting – quite correctly – that the left has been in disarray in recent years. Klein is scathing about how Democrats have been dazzled by billionaire philanthropists and endorsed a deeply flawed candidate in Hillary Clinton.”

Trump, meanwhile, is the first “fully commercialized superbrand to become President” Klein told the BBC earlier this year, arguing why his rise was predictable, largely because of the economic forces she has been describing since her first book, No Logo, in 1999. And to an extent, this latest offering is singing from the same songsheet.

Yet, interestingly, some of the strongest statements this week against Trump’s dismantling of DACA have come from the business community.

A recent survey found more than 72 per cent of the top 25 Fortune 500 companies employ DACA recipients, while the US Chambers of Commerce said the decision is “contrary… to the best interests of our country.” The Center for American Progress has estimated that the loss of all DACA workers would reduce US GDP by $433billion over the next decade.

That hit would fall most heavily on California, probably helping to explain why some of the most outspoken opponents of the decision are the leaders of big technology companies. As we saw in the opposition to the administration’s travel ban earlier in the year, the New York Times reported: “Several factors are propelling Silicon Valley to the front lines of opposition to Mr. Trump. Some have been widely noted: The companies are often founded by and run by immigrants, which made the executive order on immigration offensive and a threat to their way of doing business… Less remarked on has been the political homogeneity of tech workers. ‘It’s not like you have 60 percent of the employees on one side and 40 percent on the other,’ said Ken Shotts, a professor of political economy at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. ‘They all have the same leanings.’”

Naomi Klein’s book offers a good contextualization of how opposition to political decisions takes many – occasionally interconnected – forms and, in the current climate of multiple distractions and the speed with which information spreads, necessarily manifests itself in different, and changing, ways.

Reviewing the book for The Guardian recently, the novelist Hari Kunzru writes:

Klein wants her readers to move from refusal to resistance, from a passive stance of opposition to engagement in a programme of action. If the convulsions of the last year have taught us anything, it’s that we can’t wait for the dust to settle and clarity to emerge. Turbulence is, at least for the foreseeable future, our new condition, and we must learn to function within it. We have to teach ourselves to stand upright on a moving deck.

No is Not Enough – Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need (2017) is published by Haymarket Books.

No is Not Enough – Resisting Trump’s Shock Politics and Winning the World We Need (2017) is published by Haymarket Books.

Also published on Medium.