Remember him? It’s been just over a year since David Cameron stood down as Prime Minister, but this week he was back in Downing Street with some advice for his successor: “keep on going.”

Monday’s Evening Standard

It wasn’t his only intervention of the week. On Monday he gave an interview with the Evening Standard, now edited by a certain George Osborne. His message? The Tories need a wake-up call.

Theresa May didn’t hesitate to try and distinguish herself from her predecessor when she took up the top job. “Politics is not a game,” she pointedly remarked.

And yet the current occupant in Number 10 pulled off a move that seems eerily familiar. By taking her chances and calling a snap election, the Prime Minister finds herself in a very different position to the one she had imagined.

It wasn’t supposed to be like that.

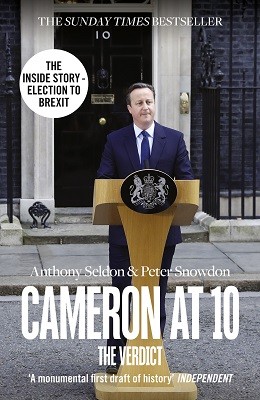

These seven words could easily sum up her predecessor’s administration – both how it started and how it finished. In Cameron at 10: The Verdict, Anthony Seldon and Peter Snowdon offer a masterful account of David Cameron’s time as Prime Minister.

What do we learn from this comprehensive piece of contemporary history? Five things stand out.

1. It wasn’t supposed to be about austerity.

When David Cameron became Leader of the Opposition in 2005, he was on a mission to modernise his party. “Let sunshine win the day,” he told the Conservative Party Conference in 2006.

Margaret Thatcher once said, “There’s no such thing as society.” David Cameron, in contrast, wanted the ‘Big Society’ to shape his core agenda. He wanted to talk about social justice, the environment, and standards in state schools.

In 2007 he made a bold move. He announced that a future Conservative government would match Labour’s spending plans. It was intended to neutralise the issue: Labour would find it harder to accuse the Tories of planning cuts to public services or tax cuts for the rich.

The financial crisis changed everything.

After Alistair Darling delivered a particularly gloomy Budget in April 2009, an aide recalls how Cameron went up to his office, “thrashing around the place and kicking the buckets. … I’d never seen him so angry at the way that Labour had mucked up the spending.”

Cameron was “rarely happy talking about economics,” but he knew the next election was going to be all about the economy and the state of Britain’s finances. Cutting the deficit – and cuts to public spending – became a central to the Conservatives’ narrative. It wasn’t supposed to be like that.

2. The Coalition suited Cameron very nicely.

David Cameron’s instinctive reluctance to let the economy dominate his agenda resulted in a confused and, ultimately, unsuccessful election campaign in 2010.

His Shadow Chancellor was much more comfortable making the argument for austerity. Before the election, George Osborne warned on The Andrew Marr Show that “early action” was needed to avoid the UK turning into Greece.

The authors note that Cameron was “uncomfortable and worried.” His heart lay with blue-sky thinking and the ‘Big Society’, championed by his advisor Steve Hilton, but his head drew him to George Osborne’s line of thinking. With Cameron torn, the “campaign was a mess.”

Lacking passion, Cameron gave only lacklustre performances in the UK’s first set of televised debates.

He felt terrible, that he’d let everybody down. He only found his stride again when he woke up on 7 May, the day after the general election, with one idea in his mind: a ‘big, open and comprehensive offer’ to the Lib Dems.

Those on the right of the Conservative Party were particularly frustrated that their leader had failed to win a majority, and furious that he immediately opted for coalition over minority government. Many suspected that he would rather work with the Lib Dems than some of his own backbenchers.

They may not be far off. Seldon and Snowdon chart more than a few difficult moments in David Cameron’s relationship with Nick Clegg, but yet he often empathised, even sympathised, with the Deputy Prime Minister. In contrast, many of Cameron’s own MPs routinely left him exasperated.

3. The moment he first felt ‘prime ministerial’.

In contrast to John Major, Tony Blair and, to a lesser extent, Gordon Brown, David Cameron was often criticised for his ‘hands-off’ approach to Northern Ireland.

Just a few weeks into his premiership, however, the new Prime Minister’s response to the Saville Report into Bloody Sunday drew widespread support.

Before he received a copy of the report, Cameron expected that he would be making some sort of apology, but it was uncertain as to how equivocal or unequivocal it would be. Indeed, the Ministry of Defence initially indicates that it will not countenance a formal apology.

When the report arrived at Downing Street at 3:30pm on 14 June 2010, the Prime Minister read it in silence before convening a meeting at 6pm with the Northern Ireland Secretary, Deputy Prime Minister, Attorney General, and the Chief of the General Staff of the British Army, and a number of key advisors. The authors describe the start of the meeting:

Cameron picks up the summary off the table and throws it dramatically back down again: ‘I’ve just read this twice. It’s the worst thing I’ve ever read and I’m going to tell you exactly what I’m going to do about it.’

The Ministry of Defence still pushes for a nuanced response to the report, but after reading its core finding that every single person shot by the Army had been unarmed, and that every killing had been unjustified, Cameron was determined to give nothing short of a full, unequivocal apology.

He delivered it in the House of Commons the next day, later reflecting: “It wasn’t my first opportunity to speak on Northern Ireland. It was my first opportunity to be Prime Minister.”

It helped to pave the way for the Queen’s historic visit to Dublin in 2011, and President Michael D Higgins’s reciprocal visit to Britain in 2014, but officials would later regret that more wasn’t done in Northern Ireland itself to build on the spirit of good will. The ‘hands-off’ approach might have been intended to reflect political maturity, but it appeared to signal a sense of detachment.

4. For better – and for worse – he trusted people.

The deep rivalry and suspicion between Tony Blair and Gordon Brown was no secret. The latter’s premiership was characterised by a sense of paranoia.

In David Cameron’s Number 10 there was a different mood, evident not least in his relationship with his Chancellor, George Osborne. The two weren’t always on the same page – the Prime Minister overruled the Chancellor when he thought he was thinking too tactically – but the closeness between the two is undisputed.

The unusual closeness between Number 10 and Number 11 helped drive the government’s agenda, but it came at the cost of blind spots and own goals.

The ‘Omnishambles’ Budget of 2012 was a low-point for the Coalition. Cameron had granted Osborne a remarkable degree of power at the Treasury, helping to allow a number of politically disastrous measures to escape proper scrutiny. Enter the ‘pasty tax’, ‘caravan tax’, ‘charity tax’ and ‘granny tax’.

His deference to Osborne echoed his relationship with other key Cabinet ministers. Most notably, he trusted Health Secretary Andrew Lansley to see through radical reforms of the NHS, failing to appreciate the detail and consequence of the reforms.

But it was perhaps Cameron’s willingness to hire and trust Andy Coulson, his Director of Communications, that constituted his most serious lapse of judgement. Both Cameron and his core team had been impressed at how Coulson, former editor of the News of the World, had been able to articulate the government’s agenda, connect with the tabloids, and get good headlines.

Initially Cameron took Coulson’s word that he had no knowledge of phone hacking under his editorship, only for a judge to later find Coulson guilty of a conspiracy to intercept voicemails. He was sentenced to 18 months in prison.

Seldon and Snowdon offer a scathing assessment of the episode:

It revealed how naïve Cameron was in dealing with figures far more worldly-wise than him, above all the Murdoch family and Rebekah Brooks, and how his openly trusting approach could be, as indeed could be that of his inner circle.

David Cameron’s youthfulness and pragmatic instincts were assets to his modernising agenda, but the Coulson affair showed how they could at times be serious liabilities.

5. It wasn’t supposed to be about Europe.

Under Cameron, the Conservatives were supposed to ‘stop banging on about Europe’. But after he scrapped his party’s pledge to hold a referendum on the Lisbon Treaty, he simply couldn’t contain the divisions inside his own party.

Osborne had reservations over holding a referendum, as did Cameron to a lesser extent, but in January 2013 the Prime Minister finally went ahead with his Bloomberg speech. It was, he felt, the only way the issue could be settled.

The key point of Cameron’s approach was not simply to hold an in/out referendum, but to first try and renegotiate Britain’s terms of membership of the EU.

Wooing Angela Merkel was a top priority. Two months before he makes the speech, he invites her to a private dinner at Number 10. After he presents a short PowerPoint to her, some of it in German, she directly asks whether he wants to say in the EU. He responded frankly:

Like many in my party, I’ve supported membership of the EU all my political life, but I am worried that if I don’t get the reform objectives I’m setting out, I won’t be able to keep Britain in. I am passionate about the single market, I am passionate about foreign policy co-operation, but if I don’t listen to British public opinion, then Britain will depart from Europe. The European project was mis-sold here, so what I want are changes that will make it possible for Britain to stay in.

She still thought he was wrong to propose a referendum, but offered him something of a reassurance: “I do get it.” She pledged to help him.

Alas, the eventual deal would not be enough to meet the expectations of Britain’s Eurosceptic press and public. Cameron took a high-risk strategy, and failed.

At 3:30am, as the referendum results came in on June 24th, Cameron knew that he had to go. When some advisors made the case for him to stay, he was adamant: “I don’t want to lead a government where I do not agree with its policy.”

As with Margaret Thatcher and John Major before him, Europe was a battle that helped to seal the fate of another Conservative Prime Minister in dramatic fashion.

David Cameron will forever be remembered as the Prime Minister who presided over Britain’s decision to leave the European Union. If you want to try and understand the circumstances leading up to that decision, to judge for yourself whether or not it was an inevitable outcome and, indeed, to reflect on Cameron’s premiership overall, Anthony Seldon and Peter Snowdon have helped to make that task possible.

Cameron at 10: The Verdict (2016) is published by William Collins.

Cameron at 10: The Verdict (2016) is published by William Collins.

Also published on Medium.