I did not know when I originally planned to visit the Linen Hall Library’s current exhibition of political cartoons last week that the subject matter would become so relevant; such is the nature of the 24 hour news cycle.

It may help to have an in-depth knowledge of the politics, history, and political history of Northern Ireland when viewing this collection, but it is not necessary. The beauty of the arrangement is that it features cartoons and caricatures from the last hundred years, in chronological order and with little accompanying information which could distract away attention. The viewer is then left to make up their own mind of the events the last century has unleashed upon this isle.

“We believe that poetry, the opposite of propaganda, should encourage people to think and feel for themselves,” said Louis MacNeice – and there is a lesson that everyone can learn from this, including academic historians.

“We believe that poetry, the opposite of propaganda, should encourage people to think and feel for themselves,” said Louis MacNeice – and there is a lesson that everyone can learn from this, including academic historians.

Dr. Liam Kennedy, in his book Unhappy the Land, wrote that it is a shortcoming of historians that they tend to read history backwards, with all the benefit of hindsight. Through keeping our lens on the world from this angle we come to see certain events as inevitable, and we may even become complacent in our political aspirations. This might explain the popularity of accusing one’s opponents of being ‘on the wrong side’ of history.

However, Kennedy added that when we read history forwards, and we think about it as it appeared when it was now, it becomes clear that certain events which we take for granted today – such as partition, the Good Friday Agreement, or power-sharing – were not inevitable, and in fact were hardly even likely.

In relation to MacNeice’s view, art such as these drawings tell the story of Irish history in a way that academic historians and journalists can’t quite manage, not least because a painting draws a far wider audience; these cartoons serve as a screenshot of their period and capture the emotion within, whether that be anger, frustration, passion, or sorrow.

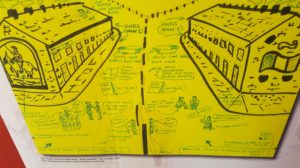

Satire is often provocative, and derides the assumptions of the establishment, academia, and the press, and in that spirit is a very crude sketch on yellow paper which is displayed: entitled,’ Old Church Road and Falls Road’ (‘Old Church’ being the English for ‘Seanchill,’ which is pronounced ‘Shan-kill’) and shows the two infamous streets side by side, with a barbed wire barricade down the middle. On each side of the we see ‘Hovels (Grade I)’ and drawings of ‘baths which the hovels don’t have,’ and then, to show the difference, on one side there is a copy of the Irish News (the truth) and on the other is a copy of the News Letter (the truth), each of them read by the ‘men not going to jobs they haven’t got,’ at the time of day their not listening to a ‘religious man from Ballymena’ or a ‘religious man from Maynooth’ (the latter, on bended knee, is obviously bare-footed).

Satire is often provocative, and derides the assumptions of the establishment, academia, and the press, and in that spirit is a very crude sketch on yellow paper which is displayed: entitled,’ Old Church Road and Falls Road’ (‘Old Church’ being the English for ‘Seanchill,’ which is pronounced ‘Shan-kill’) and shows the two infamous streets side by side, with a barbed wire barricade down the middle. On each side of the we see ‘Hovels (Grade I)’ and drawings of ‘baths which the hovels don’t have,’ and then, to show the difference, on one side there is a copy of the Irish News (the truth) and on the other is a copy of the News Letter (the truth), each of them read by the ‘men not going to jobs they haven’t got,’ at the time of day their not listening to a ‘religious man from Ballymena’ or a ‘religious man from Maynooth’ (the latter, on bended knee, is obviously bare-footed).

Comedy has great value in the politics of any country, in its ability to alleviate tension; as Tommy Sands said, “we all smile in the same language.” Though often the most powerful satire is not funny in the least but is poignant and simply allows an audience to feel and see their feelings represented; think of the SNL ‘Hallelujah’ Cold Open from the week in which Leonard Cohen died and Hillary Clinton lost the US presidential election to – name redacted –.

There were three works in particular that stood out to me. In order of chronology, they were:

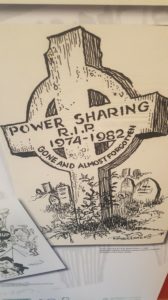

1. A sketch by Rowell Friers that depicts a Celtic cross gravestone with an inscription, “Power sharing R.I.P 1974-1982.” It is often said that the mark of great artwork is its ability to withstand time, and one could easily see the same reproduced in tomorrow’s Irish News or News Letter with the dates changed. It’s a bleak drawing, though one can imagines that it was unimaginably bleaker when it was first published, against the backdrop of de facto civil war.

2. A drawing by Nicola Jennings from 2001, of an Irish harp against a large white wall. The strings of the harp are guns, and at the edge of the picture, edging the frame somewhat, there lurks the shadow of a gunman. There is a sadness to the picture, but also a feeling of great relief and hope; it brought to mind Michael Longley’s description of the Good Friday Agreement as “a fragment from some future unimagined sky.” As the opinion columns of journalists mourn the death of the Agreement, in the wake of the newest episode of political stalemate, it is incredibly valuable to see a depiction of the hope it brought with it.

2. A drawing by Nicola Jennings from 2001, of an Irish harp against a large white wall. The strings of the harp are guns, and at the edge of the picture, edging the frame somewhat, there lurks the shadow of a gunman. There is a sadness to the picture, but also a feeling of great relief and hope; it brought to mind Michael Longley’s description of the Good Friday Agreement as “a fragment from some future unimagined sky.” As the opinion columns of journalists mourn the death of the Agreement, in the wake of the newest episode of political stalemate, it is incredibly valuable to see a depiction of the hope it brought with it.

3. A watercolour by Peter Brooks, published in 2007, which features Martin McGuinness and Ian Paisley, both now gone, standing side-by-side outside Stormont, releasing winged pigs with olive branches in their mouths into the air over Belfast city. A very simple joke which should surely raise a smile, but depicts the tentative and slow nature of the steps towards peace which were taken by people who had every reason to be nervous of the future. Again, as Tommy Sands said, “David Trimble remembered what had happened to Brian Faulkner; Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness remembered what had happened to Michael Collins.”

The ‘Laughter in the Dark – Illustrating the Troubles’ exhibition will run at the Linen Hall Library in Belfast city centre until 30th January 2018.