The shocking natural disaster of Hurricane Harvey is proving a real test of Donald Trump’s presidency. How is he rising to it? Meanwhile, what’s next in the President’s ongoing relationship with the media?

With tens of thousands of citizens in flood-ravaged Texas and Louisiana still in danger from floodwaters and the aftermath of what has been described as a “500-year” storm, Donald Trump is set to visit the region on Tuesday (although it’s still unclear at the time of writing exactly where.)

Amid his response to Hurricane Harvey, the President has come in for broad criticism; in part for not appearing to grasp the impact of the disaster, but also for the other things he seemed to regard as more important as relief efforts were getting under way – taking time on Twitter to plug a book and talk, yet again, about the size of his election victory.

Trump also managed to be accused of product placement during his emergency meetings and, after reiterating that Mexico “will pay” for his border wall, the Mexican government’s classy official rejection of such an idea ended with this statement:

The Mexican government takes this opportunity to express its full solidarity with the people and government of the United States as a result of the damages caused by Hurricane Harvey in Texas, and expresses that it has offered to provide help and cooperation to the US government in order to deal with the impact of this natural disaster — as good neighbors should always do in trying times.

But perhaps the most controversial thing was the Presidential pardon of Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio, news-dumped literally as the Hurricane was making landfall. Trump subsequently defended his decision, saying the timing meant the announcement had likely gained “far higher ratings”.

But perhaps the most controversial thing was the Presidential pardon of Arizona Sheriff Joe Arpaio, news-dumped literally as the Hurricane was making landfall. Trump subsequently defended his decision, saying the timing meant the announcement had likely gained “far higher ratings”.

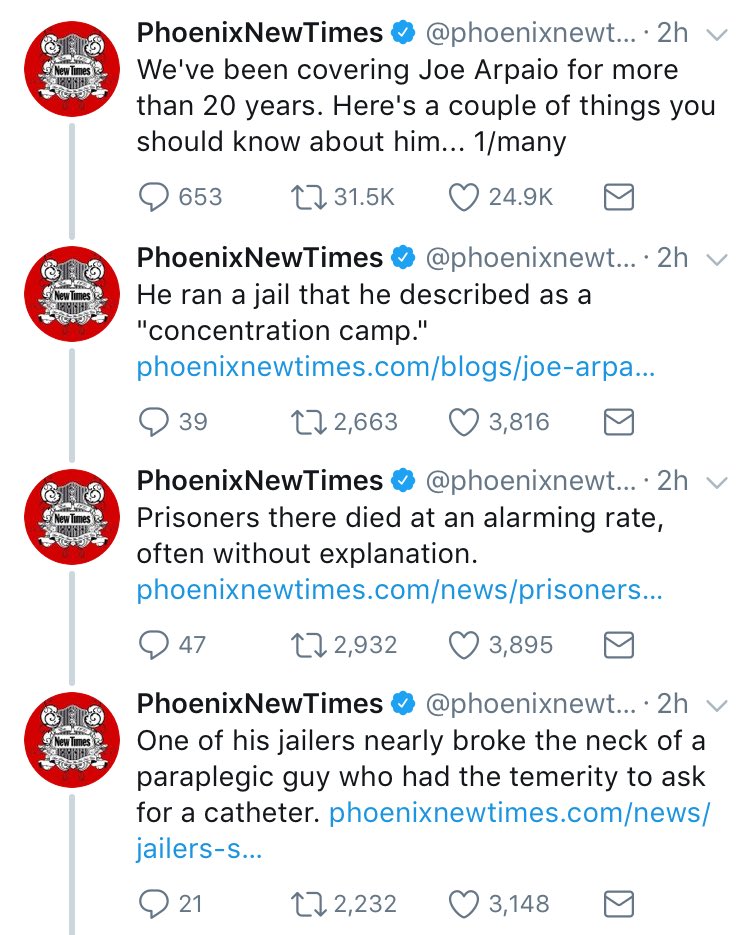

Amid wide condemnation (Slate wrote that it “affirms to the judiciary that the President has no respect for the rule of law” while Commentary said the move would “validate the left’s attempts to “tar boilerplate conservatism with the stain of bigotry”) it fell to Arpaio’s local paper, the Phoenix New Times, to lay out in a remarkable Twitter thread what they had learned in their coverage of the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office for the past two decades.

Meanwhile, Trump had used his rally in Phoenix earlier in the week to revive one of his old tricks from last year’s campaign, turning on the assembled media and encouraging his audience to join in the goading. But this was an intensity we hadn’t seen for a while. Nicholas Kristof wrote at the New York Times: “If only Trump denounced neo-Nazis as passionately and sincerely as he castigates journalists.”

In a clever analysis of the state of the strategic relationship between Trump and the press, Charlie Warzel of BuzzFeed wrote:

Trump’s war against the mainstream media is nothing new — but the positioning of the press last night in his speech is notable. His tirade against the media came early in the remarks and lasted longer than any other digression by far. The way the president described the media — as a divisive, irresponsible, and poisonous influence on the country — sounded less like a scathing critique of an institution and much more like an attack ad against a candidate…

And in the mind of Trump and his most diehard supporters, there’s very little difference. As they see it, the media — like a 2020 challenger — is perhaps one of the few institutions that pose a true threat to his presidency and re-election efforts. And, in the same way that bashing Clinton was a proven way to rally the base, passionate screeds and mockery against the media provides quick wins for Trump that obscure his biggest presidential failures (healthcare, the wall).

Breitbart, Bannon and the Base

But while traditional news organizations are obviously facing a number of challenges in covering the Presidency in the post-truth – and post-trust – world, it could be the partisanly pro-Trump media that helped him win election which could provide the best current indicator of how firm Trump’s grasp on power actually is.

When controversial chief strategist Steve Bannon was ousted from his role at the White House, an editor at Breitbart News responded with a one-word Tweet: “#War”. Despite setting off a brief flurry of searches for Edwin Starr lyrics, no-one really was sure what it actually meant.

Bannon soon rejoined the far-right web site he had run before heading up the Trump campaign a year ago, with Politico reporting that he apparently felt constrained by the limits of government and was “itching for a return to guerilla warfare”. But what people were waiting to see was whether Breitbart would turn on Trump.

The Washington Post speculated that a ‘war’ might mean a commercial revival for Breitbart, which had seen its traffic and advertising “decline precipitously over the past year, perhaps in tandem with Trump’s approval ratings.”

But beyond the machinations of the right–wing media, the current polarization of American politics and its manifestation through social platforms – particularly in the wake of Charlottesville – has thrown up an important debate about free speech; with Julia Carrie Wong writing recently in The Guardian that “..the fate of the [white supremacist site] Daily Stormer – as vile a publication as it is – may be a warning to Americans that the first amendment is increasingly irrelevant.”

Emily Bell also wrote:

The shaping of free speech is in the hands of a very centralised internationalist and entirely commercial cohort. Many people in the US and beyond are relieved that there is a buffer between their own vulnerable communities and the thuggish views of Nazis and racists; no one is particularly sorry that Nazis and their sympathisers are being driven on to the dark web. But the matter of who regulates the channels through which we communicate, the potential limits of free speech and the protections we need against authoritarianism and mob rule is far from resolved.

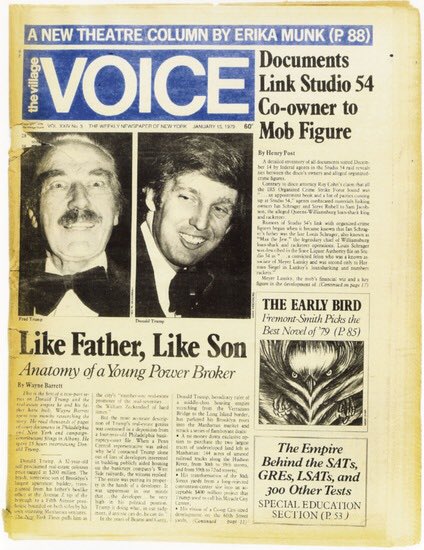

As for indicators as to the future for traditional media, maybe we shouldn’t read too much into the fact that The Village Voice – which as John Nichols of The Nation pointed out had been “exposing Donald Trump when no-one else was paying attention” – announced it was ending its print operations.

As for indicators as to the future for traditional media, maybe we shouldn’t read too much into the fact that The Village Voice – which as John Nichols of The Nation pointed out had been “exposing Donald Trump when no-one else was paying attention” – announced it was ending its print operations.

Perhaps, at the end of the day, as Matt Taibbi suggested this week, we should blame the media for creating a world dumb enough for Trump. “If a meteor crashes into Jello night at the Playboy mansion,” he says, “it doesn’t matter if you send Edward R. Murrow to do the standup. Some things sell themselves.”

But there’s hope. In a week where fact-checking site Politifact celebrated its ten-year anniversary, the reality – as opposed to the reality show – of Hurricane Harvey showed journalism doing, simply and efficiently, what it’s supposed to do.

Rough waters

As for the immediate outlook for the President away from the eye of the storm, persistent journalism by the Washington Post and the New York Times has ensured that the Russia story isn’t going away anytime soon. After the Post reported on a potential business deal for a Trump Tower in Moscow during the campaign, the Times added quotes from jaw-dropping emails between Russian-born developer Felix Sater and Trump’s lawyer Michael Cohen.

As Politico’s Michael Grunwald tweeted: “It’s like connect the dots with only two dots.”

In foreign policy, with a new approach to the war in Afghanistan about to begin, a speech by Defence Secretary Gen James Mattis urged troops to “hold the line until our country gets back to understanding and respecting each other and showing it.” Meanwhile, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson told Chris Wallace on Fox News that President Trump “speaks for himself” when it comes to “values”.

As if all that wasn’t enough, North Korea’s latest provocative missile launch, overflying Japanese air space, has escalated that situation and will require some kind of official response.

As Texas continues to deal with the fallout from what has been a truly unprecedented disaster, so – some will argue – does the rest of America.

Also published on Medium.